The Me Too and Time’s Up campaigns have broken the silence on endemic sexual harassment, pay inequality, and lack of true racial and gender diversity in showbusiness and the media.

Thousands of women, BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic), LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) professionals and allies have come out to demand their stories be heard.

They demand the right to feel safe at work, free from having to use sexuality as a bartering chip. And they insist the white, heterosexual men running the industry acknowledge the world no longer only wants to see the imaginings of white, straight men on screen.

But as the industry begins reframing its entire power structure, has enough been done to ensure this is more than a passing phase?

“Speaking your truth is the most powerful tool we all have,” urged Oprah Winfrey at the Golden Globes in January. Launching the Time’s Up campaign against harassment in the entertainment industry, her televised crie de coeur, with its heavy focus on racial injustice, marked a pivotal moment in the conversation.

No longer was this merely about stopping furtive male hands on frozen knees, but taking to task an industry that had for too long sustained sedimented, white male power.

Then in February, Marvel’s Black Panther was released. For decades, Hollywood executives had argued that the only reason BAME protagonists didn’t feature was because the audience wasn’t interested in them. In its first fortnight, the movie took more than $400 million at the US box office and by April had become the biggest grossing superhero film of all time. Suddenly the “no interest” argument no longer stood and the execs conceded. How truly to “represent” finally mattered.

No longer was this merely about stopping furtive male hands on frozen knees, but taking to task an industry that had sustained sedimented, white male power

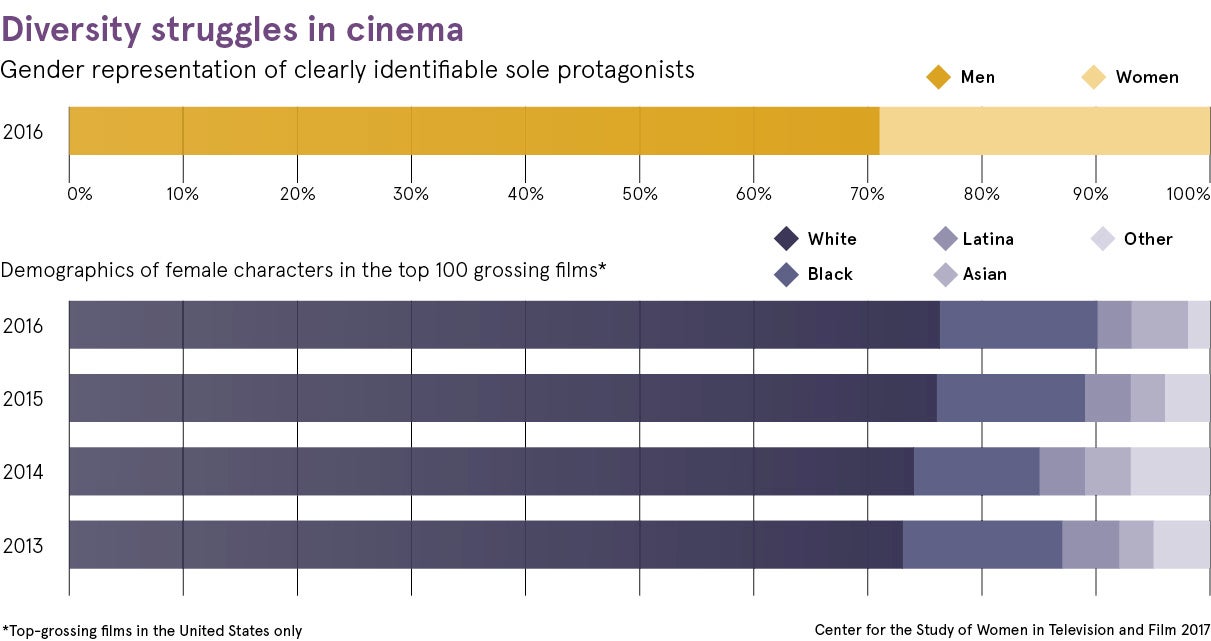

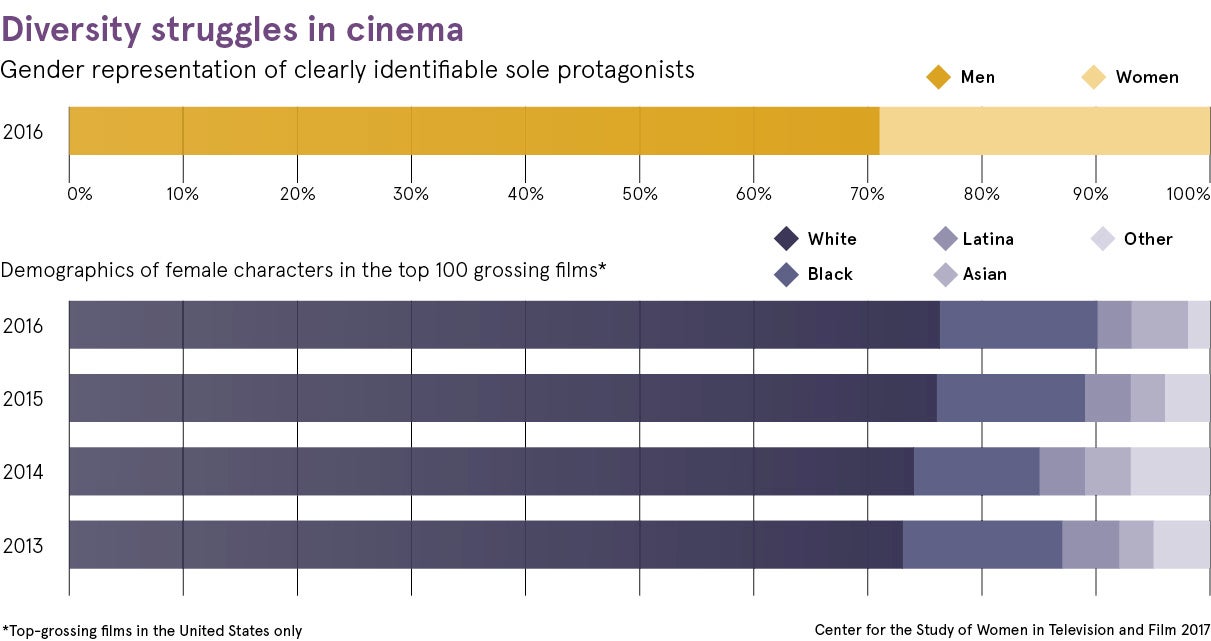

Not that the numbers didn’t already speak for themselves. In 2016, the Institute for Diversity and Empowerment at Annenburg, University of Southern California, found that during a ten-year period from 2006, 71 per cent of speaking characters on screen were white, while only 18 per cent of productions contained a gender-balanced cast. Women, in particular Latin and Asian characters, were significantly oversexualised, while only 2 per cent were LGBT. And some 70 per cent were Caucasian men.

At the Oscars in March, actress Frances McDormand had a solution. Building on Winfrey’s call to arms, she championed the use of inclusion rider agreements, clauses that an A-list actor or actress can insert into contracts demanding all working on the production be a diverse mix of ethnicities, races and genders. Stateside, a plethora of stars have now pledged to use them, including Brie Lawson, John Boeyga, Michael B. Jordan, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. In the UK, the Labour Party has called for inclusion riders to be required for films to receive tax relief.

LGBTL

LGBTL

Still, what good is inclusion if there remains a secret gender pay gap? This was the next question posed by the Time’s Up campaign, when it was revealed that Emma Stone, 2017’s top-paid actress at $26 million, was earning $40 million less than Mark Walberg, the top-paid actor during the same period.

When news broke that The Crown’s Claire Foy was earning less for her role as the Queen than co-star Matt Smith was for the Duke of Edinburgh, Smith himself spoke out: “She’s the Queen for god’s sake. It’s ridiculous.” Foy has since received £200,000 back pay and an apology from the show’s producers. Alluding to how things have changed since January’s awakening, she said: “It’s “amazing… the conversations people are having now.”

While the heads of alleged harassers continue to roll – Bill Cosby and R. Kelly are but the latest – the focus is now on demonstrative inclusion and funding for those facing legal action for outing abuse. Time’s Up legal defence fund has raised $21 million since its launch, helping some 2,500 individuals facing lawsuits from those who had allegedly harassed them. “The retaliation people face is real,” says Fatima Goss Graves of the US National Women’s Law Center.

But so is the momentum. #MeToo has trended in 85 countries, while the fashion industry, politics, advertising and Bollywood have also all called time on abuse. And now, even the press, formerly praised by Winfrey for helping to expose “tyrants and victims, and secrets and lies”, is under scrutiny.

Time Up’s latest collaboration is Press Forward, a coalition of female journalists campaigning against harassment in American newsrooms, sourcing funding from the Poynter Institute and McClatchy News to implement reforms. As Dianna Pierce Burgess of Press Forward explains: “It’s important we create a news standards and practice document – a blueprint with a new code of conduct and ‘best practices’ for newsrooms, large and small.”

So, what will truly change how the media and entertainment industry operates? The realisation that their bottom line depends on it, says Natalie Campbell, co-host of Badass Women’s Hour. “If they don’t change how they work, understand their responsibility to society, they simply won’t exist in ten years’ time,” she says.

Meanwhile, as the small and silver screens teeter on the edge of “woke”, getting a sudden understanding of what’s really going on, one story of harassment lingers: whether that bastion of white male privilege himself, US President Donald Trump, bribed an adult actress to stay quiet about a sexual encounter. “Speaking your truth” won’t yet tease apart every power struggle. But in ten years’ time, who dominates that cultural conversation could look very different.