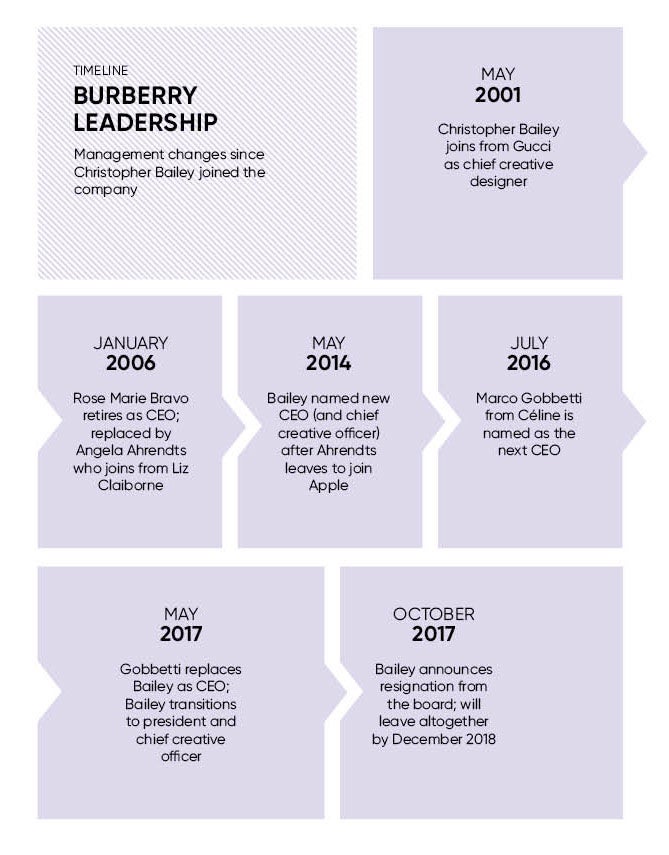

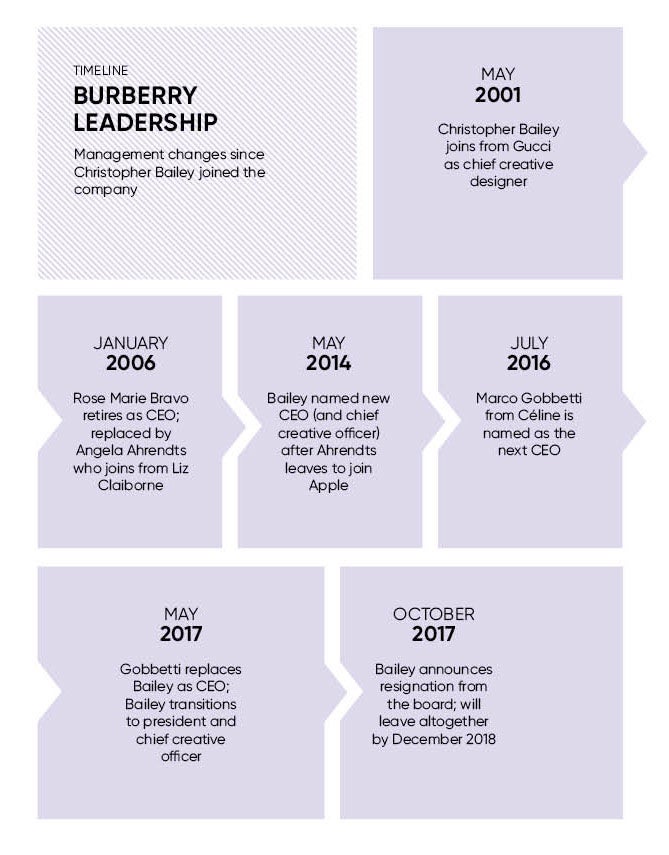

When Christopher Bailey announced in October he would be stepping down as chief creative officer and president at Burberry in 2018, many lamented the end of an era.

In the 2000s, the design guru was credited with transforming Burberry from a down-on-its-luck label into a global British icon, with fashion that married old-world class with progressive elegance. Its scarves, bags and trademark trench coat became fashion must-haves, A-listers from Kate Moss to Emma Watson became brand ambassadors and sales climbed.

But after Mr Bailey took the reins at the company as chief executive in 2014, his luck changed.

Turbulence hit the luxury market and the firm’s profits ebbed. Some investors argued he lacked the business acumen to turn the ship around and a flurry of executives quit.

In July 2016, Burberry announced that Marco Gobbetti of French fashion label Céline would take over the CEO role, with Mr Bailey keeping the title of president and refocusing on his creative director role.

But the writing was on the wall. Soon after Mr Gobbetti started in July 2017, Mr Bailey decided to move on.

Now the firm is gearing up for a change of direction, but still faces major challenges; recapturing the dynamism Mr Bailey originally brought to the firm won’t be easy.

Certainly Mr Bailey’s will leave “big boots to fill”, says Professor Mark Ritson from Melbourne Business School.

“Many do not realise that in the late-1990s Burberry was a basket case,” says Professor Ritson, who worked in the world of luxury brands for 15 years, including at Givenchy and Céline. “It had forsaken its authenticity for mass-market sales growth and lost its charm.”

Mr Bailey, who had previously worked for Gucci and Donna Karan, changed all that. As a designer, then chief creative officer from 2009, he killed off the “chav” reputation the label had acquired in the early-2000s, due to a proliferation of lower-priced Burberry products, and created more subtle and diverse fashion that riffed on Burberry’s heritage.

“Today Burberry exists in the same galaxy as Prada, Gucci and Dior, while still being far more accessible that those brands,” says Professor Ritson. “That was down to Chris.”

Mr Bailey also had a flair for marketing and under his tenure Burberry was one of the first luxury labels to experiment with social media, striking up advertising partnerships with Snapchat, Periscope and Instagram.

And in keeping with his populist touch, he embraced the “fast fashion” trend, an anathema to most luxury brands, launching Burberry’s first “see now, buy now” show at London Fashion Week in 2016. This let fans purchase “seasonless” items immediately after they were presented on the catwalk, rather than having to wait months.

It all translated into strong growth, but as sceptics point out, Mr Bailey didn’t do it alone. Angela Ahrendts joined the company in 2006 as CEO and together they trebled the company’s worth to £7 billion by 2013.

But when his co-pilot left in 2014 and Mr Bailey became sole captain of the brand, he lost his flow.

Rogerio Fujimori, luxury analyst at RBC Capital Markets, says: “In the largest luxury companies, we typically see a successful partnership between the chief executive and the creative director, since both roles require very different skills.

“In fact, Christopher Bailey had extremely successful partnerships with previous Burberry CEOs Angela Ahrendts and Rose Marie Bravo. But when Mrs Ahrendts left, Mr Bailey became overstretched against adverse luxury market conditions seen in 2015-16.”

Those conditions included a slowdown in luxury spending in 2015 in crucial markets such as China and the United States. A string of terror attacks also kept shoppers off the streets of Paris for lengthy periods in 2016.

Burberry’s financial performance slumped, with pre-tax profits down 10 per cent in 2015 and a further 5 per cent in 2016. Expressing their displeasure, a third of investors in the firm voted against Mr Bailey’s remuneration last year and Marco Gobbetti was swiftly brought in by Burberry’s board.

The firm’s leaders face a tough job to regain lost ground and success is not assured. Mr Gobbetti’s initial attempts to reassure shareholders have also fallen short.

On November 9, the Italian unveiled a “no pain, no gain” strategy to push the brand ever deeper into luxury territory, taking Burberry out of all but the most exclusive stores, first in America and then more widely.

The plan is not sensible because it doesn’t spread risk, says Eric Musgrave, a fashion commentator and former editorial director of Drapers, the fashion magazine.

“The most successful brands typically have a wide spectrum, so you present yourself as high-end, but also have more accessible products like fragrances and accessories that are a gateway to the brand. It’s not wise to just focus on selling £3,000 handbags,” he says.

But Steve Clayton, manager of a Hargreaves Lansdown investment fund that holds a position in Burberry, thinks the idea of focusing on exclusivity makes sense.

“True luxury brands command immense pricing power and generate fabulous margins and cash flows,” says Mr Clayton. “As Mr Gobbetti puts it, ‘We will play in the most rewarding, enduring segment of the market’. That’s a prize worth paying for.”

Most believe Burberry has the capacity to retain its position as one of the world’s most iconic fashion brands and in a promising sign, luxury spending has picked up in key markets such as China.

But as Mr Bailey’s own fall from grace shows, even the most successful operators in the fashion world can lose their mojo – something Mr Gobbetti would be wise to remember.