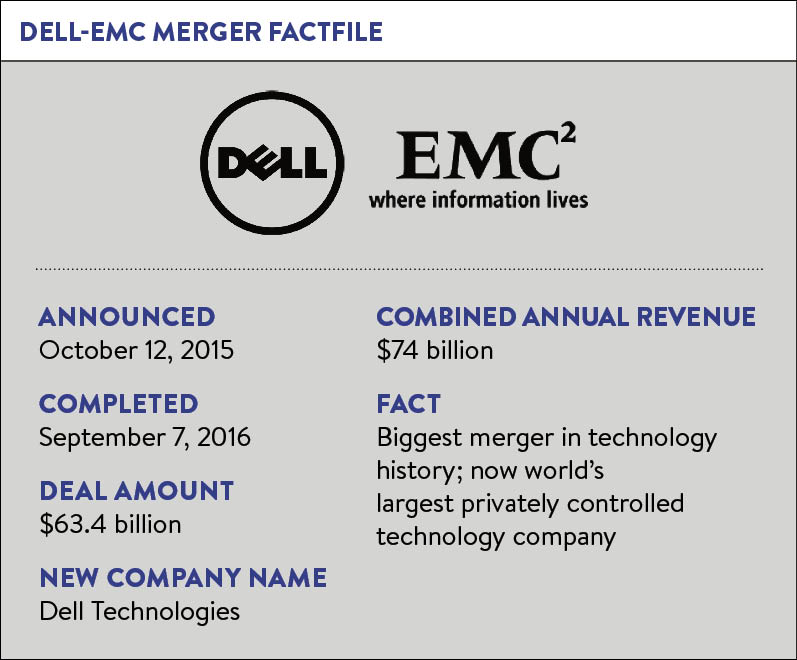

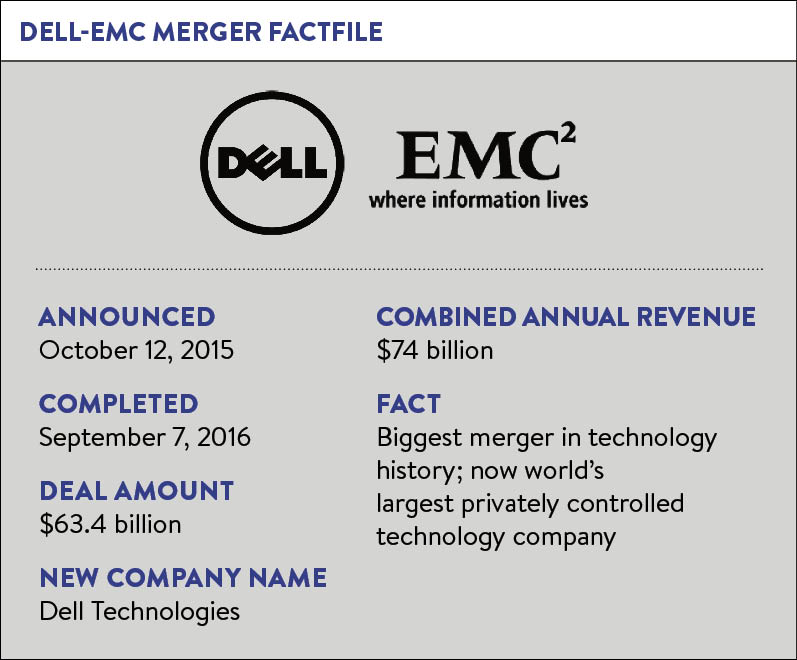

“It started with Michael Dell and Joe Tucci,” says Tom Sweet, referring to the $63.4-billion merger between Dell and Tucci’s storage company, EMC. “Joe and Michael go way back. They’re business colleagues and they’re friends. They’ve had an active dialogue over the years about the industry, how the companies might work together. And you know that EMC had a number of activist investors who had been advocating for change in the EMC structure over the last few years. So EMC was under some pressure to maximise shareholder value.”

Now, thanks to the biggest merger in technology history, some of the pressure is off EMC. The highly leveraged deal, which leaves Dell with almost $50 billion of debt to pay down, was made possible by the creation of an unusual “tracking stock” tied to VMware, an EMC subsidiary, which allows the newly formed Dell EMC to keep control of the business, despite owning less than 50 per cent. Having taken his eponymous company private again in 2013 in a $25-billion deal, Michael Dell has made no secret of how much he has enjoyed being free from the tyranny of the “90-day shot clock” that comes with being a public concern.

“That allows us to take longer-term views around investment decisions, strategic decisions and opportunities,” says Sweet. The hope is that the consolidation of Dell’s hardware business with EMC’s cloud storage capabilities will combine with the scale and expertise of its sales force and supply chain to drive a successful long-term strategy. But it’s worth noting that some in the industry aren’t so sure. The chief executive of one of Dell’s biggest rivals told the Financial Times (anonymously) that the merger merited the description infamously bestowed upon the ill-fated Hewlett-Packard purchase of Compaq of “two garbage trucks colliding”.

What being a CFO means

For his part as Dell’s chief financial officer, has been working hard to make sure that doesn’t happen. When he speaks to me from the company’s headquarters in Round Rock, Texas, he says the weeks since the finalisation of the merger have mostly been spent on integrating Dell and EMC as smoothly as possible, “spending time on policies, processes” and working out “how do we integrate to go to market?” Beyond that, Sweet runs off a list of responsibilities that fall under his “classic CFO role” such as financial reporting, accounting, business support, back-office transactional systems, investor relations, treasury and tax.

But he also heads up Dell Financial Services, which offers leasing and other forms of finance for customers, is taking control of a divestiture process that will see the company shed some

of its assets and is in charge of a strategy team, which “helps Michael and the business leaders think about position in the market and the strategic direction of the company”.

I’m providing inputs and thoughts, and my observations, helping Michael think through some of the strategic decisions he has to make

If it sounds like Sweet has a lot on his plate, then he may not be alone. In a report published by EY, the role of today’s chief financial officer was described as “a job that may be too big for any one individual to do well, given all the responsibilities and the incredible contrast between the day-to-day tactical controllership functions, and the very long-term, strategic, executive functions”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sweet doesn’t go that far, but he does echo a view, which has gained currency in recent times, that the role of the chief financial officer has become more strategic, rendering its holder a sort of de facto “co-pilot” for the chief executive.

“I do think that I’m providing inputs and thoughts, and my observations, helping Michael think through some of the strategic decisions he has to make and that we’re making as a company,” he says. “I have the strategy team underneath me and we’re tackling a number of issues about how we play in certain areas and certain markets. So I do think the role has expanded from a classic ‘close the books, report the results and manage the capital’ to a much broader, quite frankly more interesting, dynamic job, which is what interests me about it.”

Some financial chiefs’ remits, of course, have swelled more than others. Mark Evans joined the list of former chief financial officers to have taken the top job when he was installed as chief executive at telecoms giant O2 earlier this year. Anthony Noto hasn’t done the same, yet, but has managed to accrue power and influence at Twitter after buying more stock while other senior executives were only selling, taking on more responsibility and working alongside a part-time chief executive in Jack Dorsey, who splits his time between Twitter and payments company Square.

But even the chief financial officers who are content with the co-pilot’s seat are influential; it’s their hands on the purse strings, their say-so governing whether projects get the green light or are sidelined.

Understanding the business

As you might expect, Sweet, who has been with his current employer for just shy of 20 years, the last three of them as the financial chief, is full of praise for his boss. He cites Michael Dell’s knowledge of the industry, its trends and his thoughtfulness, and says: “I love working with Michael. He’s willing to debate points, he has a point of view, generally, as do I, generally.” He laughs. “I view my job as the CFO here to help enable his vision.”

Asked what he’s like as a boss himself, Sweet jokes that it’s probably a “dangerous question” and good naturedly inquires whether I have any inside knowledge from his team. A little more seriously, he admits to being demanding, but says he avoids micro-management. “I have an incredibly talented organisation and part of what I try to do is put the best people in the right jobs so they can maximise their capabilities,” he says. “So we lay out expectations – the stuff they need to get done to support the company and where we’re headed – and then turn them loose to let them run their function. It’s generally been a good formula for me.”

Sweet says that he “learnt the balance of driving a finance organisation within the context of enabling a business model” from two of his predecessors at Dell, former American Airlines chief executive Don Carty and Tom Meredith. Of his peers, he picks out Microsoft’s Amy Hood and Intel’s Stacy Smith, who recently took on a broader operations role, as operators who embody the strengths needed in a modern chief financial officer.

“I think you’ve got to understand the business – your own company and the industry,” he says. “So, do you understand your business? Do you understand the business model? Do you understand the levers that you have available to you? Do you understand how your business fits into the trends that are happening in the industry and the environment, and can you shape and influence the company to move in the direction that you think is appropriate?”

But he adds: “To become that strategic partner, you’ve got to do the basics well. Because if you screw up and you’re not filing your tax returns properly, or have a reporting issue or a recording issue, then the other stuff doesn’t really matter.”

Plans and predictions

Looking to the future, Sweet says that using data and analytics to make predictions is likely to become more important as the company invests resources and uses developments in the technology, even if limitations are likely to remain. “As you might imagine, the technology sector can be relatively volatile. So it’s not a case of saying ‘we’re going to grow at 1.5 per cent for the next 20 years’, it depends on demand and macro-economic circumstances. But trying to do a better job of predicting business performance and enabling business decisions is something that we’re pretty focused on. I think using predictive analytics is a huge win for us, but we’re just in the infancy of trying to do that,” he says.

Another of Sweet’s chief concerns will be managing the teams under his command and trying to ensure Dell’s global finance workforce of 7,500 people is enriched with the right talent, wherever it comes from. “Technology is enabling our people to work anytime anywhere,” he says. “So the workforce dynamics around my finance team are changing. You think about flexible working, work-life balance and things of that sort – I’m looking for the best talent, even if it’s not necessarily located somewhere I have an office. Workforce productivity tools are changing the shape of our finance function pretty rapidly.”

Sweet acknowledges that there have been times when this idea has been counter-productive. Marissa Meyer’s decision to completely axe flexible working at Yahoo! in 2013 is the most notorious instance of “modern” attitudes to such flexibility back-firing, but it’s not unique. Best Buy and Reddit are among the big names to have done the same. Sweet, though, believes it has a place at Dell.