The US Federal Reserve’s core monetary policies have become ineffective and incoming chair Jerome Powell must find radical new solutions to stop the world tumbling into another crisis, say economists.

Mr Powell will become head of the world’s most powerful central bank in February. But without a creative new plan, he could quickly run out of monetary tools if, as many predict, the US economy starts overheating next year.

The debate centres on whether the Fed’s core policy of using interest rates to boost inflation is still fit for purpose.

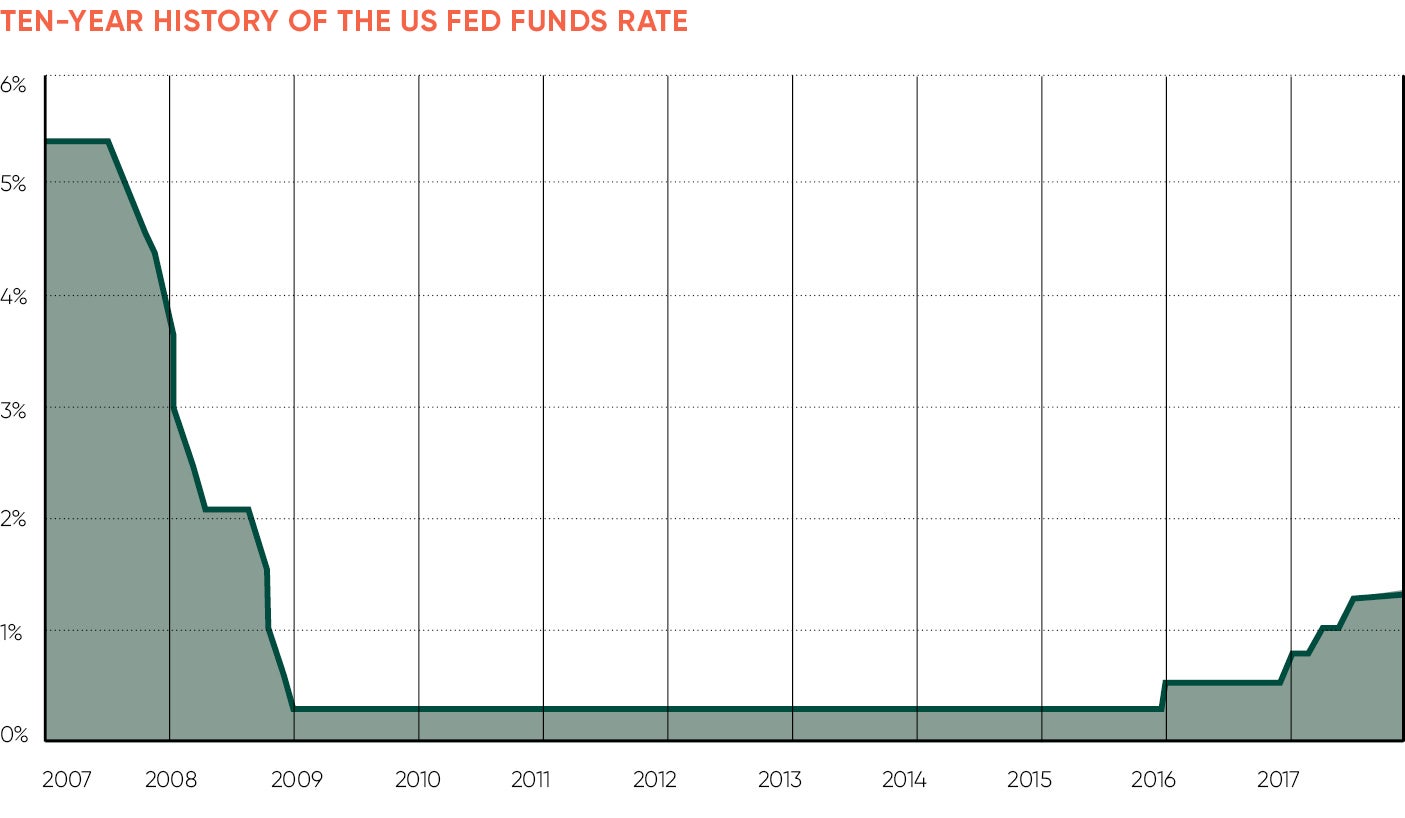

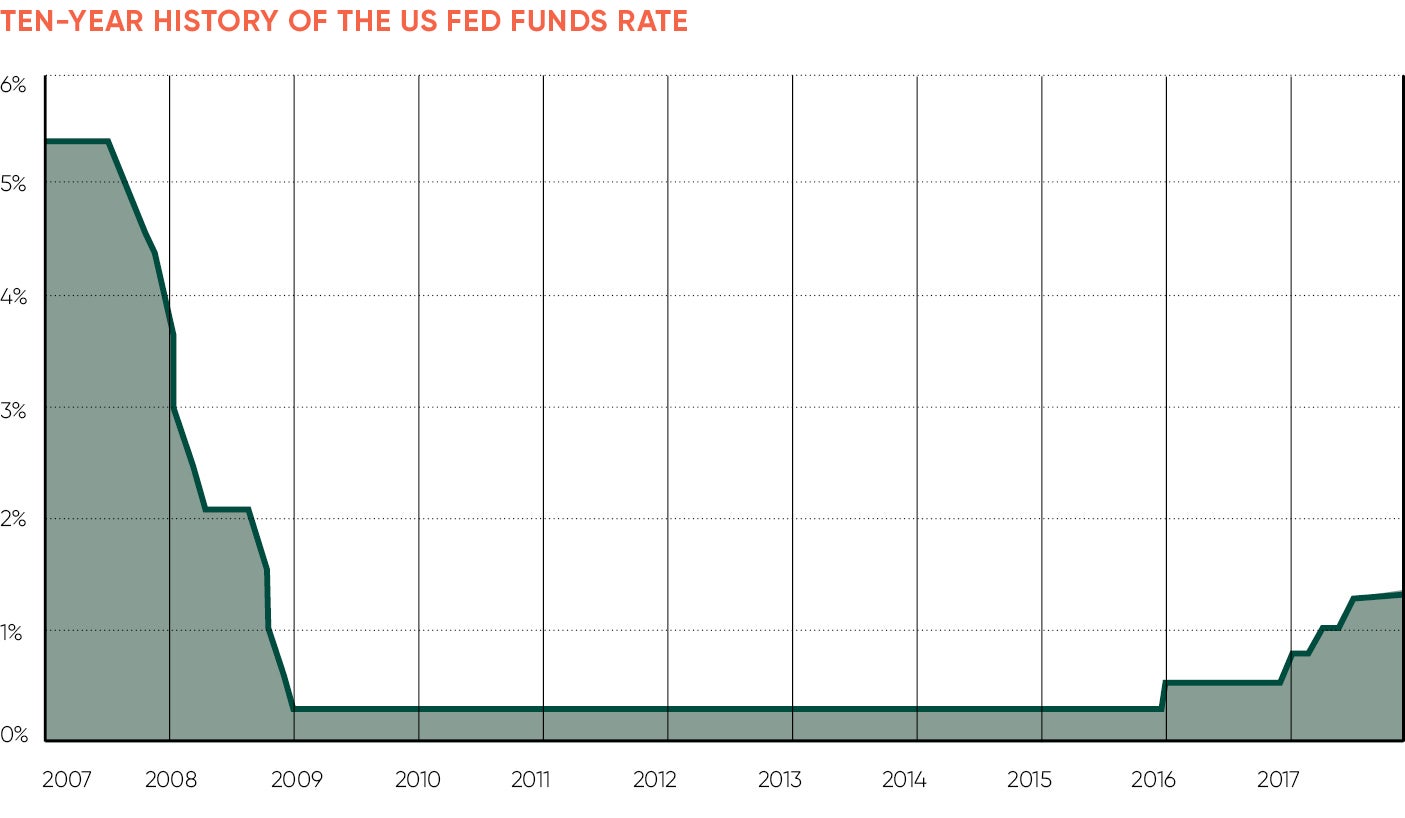

Since the 2008 financial crisis, central banks including the Fed have kept interest rates ultra-low in a bid to boost inflation, which has historically tracked other growth measures closely. Since 2015, the Fed has started raising rates gently again, which it says has kept growth steady.

But many are now saying the lack of a more aggressive approach has allowed the economy to start growing too quickly. They argue that inflation has remained deceptively low and is no longer such a reliable marker of growth due to structural issues related to technology and globalisation. The dangers are another stock market bubble and an inability to address a downturn when it bursts.

Calls for a rethink on monetary policy frameworks are therefore growing, from outside bodies such as the Bank of International Settlements and from Mr Powell’s own colleagues, including San Francisco Fed president John Williams.

Some are urging the Fed to reassess its inflationary targets or reduce focus on inflation altogether. Some think that it may need to revert to quantitative easing (QE) again, because low interest rates will give it less space for manoeuvre come the next downturn.

Others, including Ken Rogoff, professor of public policy and economics at Harvard University, say Mr Powell should take the dramatic step of phasing out paper money, which would enable the Fed to also use negative interest rates.

Mr Williams has also suggested untried measures such as targeting income and prices instead of inflation.

Jeremy Lawson, chief economist of Aberdeen Standard Investments, is one of many who warn that the Trump administration’s planned tax cuts risk overcooking the US economy, which is already growing above trend.

“Central banks everywhere are having difficulty generating inflation, [supposedly] to improve the economy,” he says. “Underlying inflation has not budged, raising questions about whether monetary policy is fit for purpose. For example, should they put less weight on inflation and more on other financial factors? These debates will increase and likely become binding in the next downturn.

“How will the Fed respond when the downturn comes? Slow rate increases mean it may have less space to respond with rate cuts. So the question of whether to retrigger [QE] will come up again. That could create financial volatility.”

Keith Wade, chief economist at Schroders, says the potential for tax cuts to exacerbate overheating is not yet factored into Fed policy. He would have preferred a Fed chair that favours tighter monetary policy compared to Mr Powell who tends towards a neutral stance.

“The US is reaching the end of its cycle,” says Mr Wade. “Policy on interest rates and quantitative easing has been too loose, too long, creating potential bubbles.”

He believes inflation is lagging other data, such as employment. “Structural issues have pushed inflation down, but it will start increasing next year as these work through,” says Mr Wade. “You can see it already in some data.”

One major reason for Mr Powell’s appointment was that he is perceived to be more favourable towards financial sector deregulation. But rolling back regulation could also be a mistake, returning the economy to strong debt-led growth as banks increase lending, with more potential overheating.

Mr Powell might have to tighten policy more aggressively than he expected, says Mr Wade. Aggressive tightening typically leads to recession, but he will have less room for manoeuvre.

One of Mr Powell’s first actions should be to lay the groundwork for negative interest rates

“So there will be pressure on Powell,” says Mr Wade. “During the financial crisis, we were fortunate to have [previous Fed chair] Ben Bernanke, who could think outside the box with QE. I wonder, in a crisis, whether Powell will be able to reach for the rights tools.”

Professor Rogoff says one of Mr Powell’s first actions should be to lay the groundwork for negative interest rates.

After the financial crisis, cutting interest rates well below zero would have stimulated growth and inflation. But central banks have been unable to do this for fear it would drive investors out of banks and Treasury bills to stockpile cash.

“This is why negative interest rate policies in Europe and Japan only had modest effects,” says Professor Rogoff. “This constraint has paralysed monetary policy in advanced economies and is likely to be a recurring problem in future.”

The Harvard academic adds that, as explained in his 2016 book The Curse of Cash, phasing out paper money would solve the problem.

“That ensures that, in another deep recession or financial crisis, negative interest rate policy does not spark a wholesale run into cash,” he says. “Another idea the Fed should study is raising the inflation target, but this is a distant second best.”

The Federal Reserve board of governors were contacted, but declined to respond.