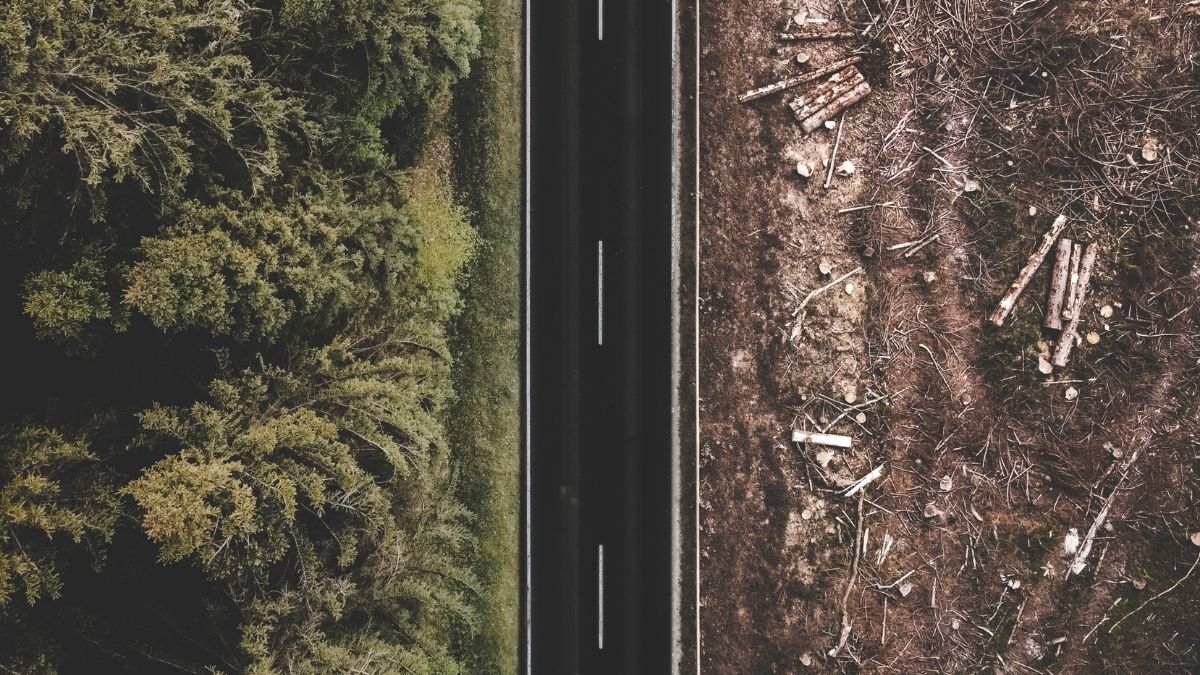

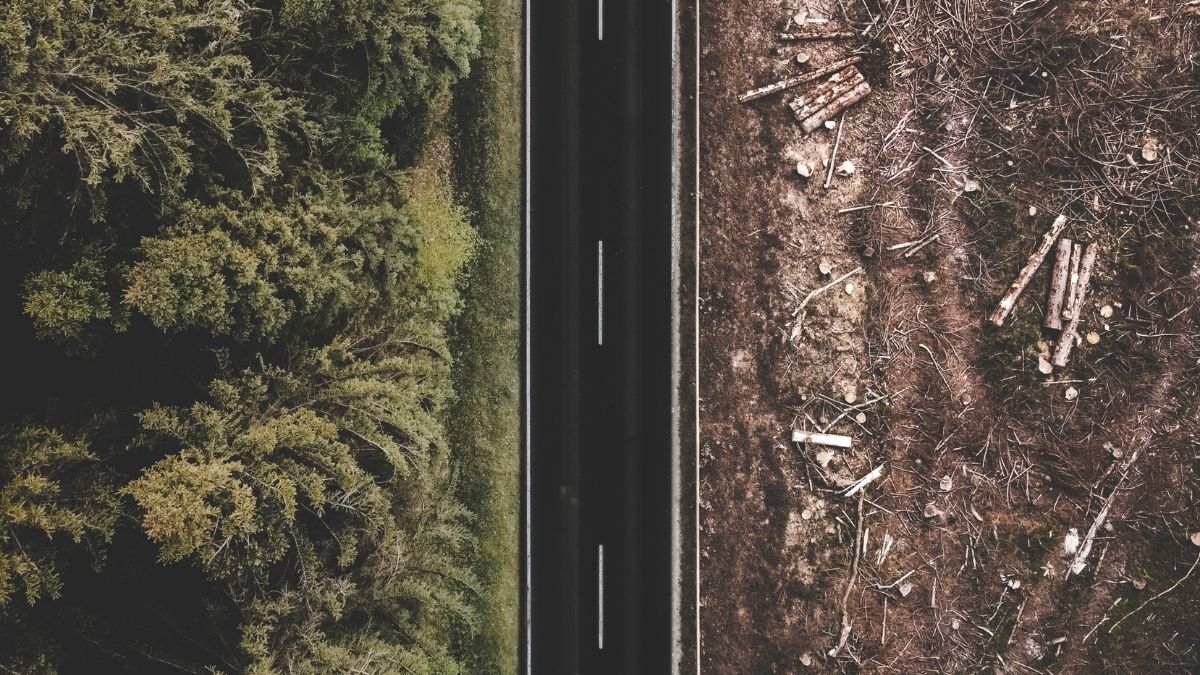

New EU legislation marks a global first in the battle against deforestation, targeting all aspects of the problem, not just illegal examples. The proposed law has been widely welcome by campaigners, though some wonder if it goes far enough.

Tackling deforestation is a central pillar of the EU’s plan to tackle the climate crisis. In November, the European Commission (EC) proposed draft legislation that would ban all beef, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, soy and wood products that are linked to deforestation – and those derived from them – from entering the trading bloc.

If supported by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU, it could become law by the end of 2022 or early 2023. It’s important because it would cover all deforestation, not just that deemed illegal in the country of origin, as was the case in the UK’s recent Environment Bill.

The response to the draft law from NGOs has been broadly positive. Nico Muzi is Europe director for the environmental advocacy organisation Mighty Earth. He notes that although the regulation has been a long time coming, having been first discussed in 2008, it is nonetheless visionary.

“It’s a world first in terms of addressing the responsibility of European consumers in driving deforestation, both legal and illegal,” he says. “That sets a big precedent, as it’s saying there is no ‘legal’ deforestation. Any deforestation is a violation … it goes beyond the legality of the [origin] country.”

Michael Rice, forest-risk commodities lawyer at environmental law charity ClientEarth, is also supportive of the draft law. “The EU is the world’s single largest market, so it’s a massive signal to the agriculture sector globally that we can’t carry on with business as usual,” he says.

Rice is impressed with the mandatory due diligence embedded in the regulation, which includes a requirement for companies to provide the exact locations of the farms where they source their products. “It’s a big step forward in terms of global environmental governance, what we call full supply chain traceability,” he says. It means companies can no longer get away with blind spots in their supply chain.

For Rice, it appears the EC learnt good lessons from previous EU regulation on illegal timber, which had some ambiguity in terms of compliance that made it harder to police. Enforcement will now be in the hands of the member states, each of which must set up agencies to monitor compliance with the law.

Challenges ahead

Despite the widespread support, there are some criticisms of the legislation. It doesn’t include other significant deforestation-risk commodities like rubber and maize, for example, and only applies to deforestation in actual forests.

“It doesn’t cover other types of ecosystems that are both high carbon stores and habitats for lots of biodiversity,” Muzi explains. Mighty Earth and other European NGOs “are pushing to extend this part of the regulation to cover specifically savannahs, wetlands and peatlands”.

Lots of Southeast Asian palm oil is grown in former peatlands, not forests, Muzi says. These are huge carbon and methane sinks, so it doesn’t make sense to leave them out of the legislation. The same goes for soy, which is grown extensively in the Cerrado Savanna in Brazil.

“[The legislation] was politically very complicated, so they want to get it right and address forest loss first, then move on to other ecosystems,” Muzi says. But he notes there is a review clause after two years, where the EC will test the impact and feasibility of including other ecosystems.

The law has also been criticised for not including the human rights fallout from deforestation. “Chopping down trees often goes hand in hand with land grabbing and very significant and long-lasting human rights impacts for indigenous people and local communities in forest areas,” says Rice.

Until now, companies trading in forest-risk commodities could rely on voluntary third-party certification schemes to vouch for their products’ sustainability. But the system wasn’t working well enough, hence the need for EU law.

Still, the companies that engaged with voluntary certification schemes until now and tried to make their supply chains more transparent and traceable will be at an advantage moving forwards.

“This law will level the playing field and the frontrunners will benefit because they now won’t be penalised for taking the step [to make their supply chains more sustainable] because everyone will have to do it on a market-wide basis, and that extra cost will be diluted by so many consumers [450 million in Europe],” says Muzi.

Business impact

Many businesses wanted the law and in fact lobbied for it. A Unilever spokesperson says: “We have long been calling for mandatory, EU-wide due diligence legislation covering environmental impacts, land, human and labour rights. The initiative is fully in line with our deforestation-free supply chain commitment.”

Cathryn Higgs, head of food policy at The Co-op, had hoped the UK’s Environment Bill would be more in line with the EU’s draft law in terms of including illegal and legal deforestation. “We have publicly urged the UK government to set robust due diligence requirements as part of the Environment Bill, reflecting some of the elements of the EU’s draft such as covering both legal and illegal deforestation and conversion across all ecosystems,” she says. “It’s vital to create a level playing field, so that all businesses of all sizes and sectors are expected to conduct meaningful due diligence when sourcing at-risk forest commodities.”

As a result of the EU law, companies will have more leverage with suppliers to make their supply chains more sustainable. “Every company in Europe trading in these commodities [will be] asking all of their suppliers to deliver that traceability at the same time and that is really going to drive change at the global level,” says Rice.

Does this mean we’re likely to see more regional boycotts or businesses banning certain products, such as palm oil, from their supply chain? Boris Saraber is director of operations at the environmental non-profit Earthworm, which works with large corporations including Nestlé and Colgate. He isn’t sure that’s the best approach.

“There is a point at which you need to take action to de-link from suppliers who are not engaged to build change,” he says. However, if you’re sourcing from a certain region, there are likely to be many raw materials sourced from that area, “so you’re much better off using responsible purchasing power to build long-term change in that region.”

New EU legislation marks a global first in the battle against deforestation, targeting all aspects of the problem, not just illegal examples. The proposed law has been widely welcome by campaigners, though some wonder if it goes far enough.

Tackling deforestation is a central pillar of the EU’s plan to tackle the climate crisis. In November, the European Commission (EC) proposed draft legislation that would ban all beef, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, soy and wood products that are linked to deforestation – and those derived from them – from entering the trading bloc.

If supported by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU, it could become law by the end of 2022 or early 2023. It’s important because it would cover all deforestation, not just that deemed illegal in the country of origin, as was the case in the UK’s recent Environment Bill.