When Boohoo was accused of modern slavery in 2020 because of the working conditions in one of its suppliers’ factories in Leicester, its share price tumbled by 18%, retailers dropped the brand and it faced the possibility of a US import ban. The case was an object lesson in the importance of supply chain due diligence – and handling the communications around it effectively.

Boohoo is far from the only high-profile UK firm to have been caught up in a scandal affecting a supplier. Dyson is facing compensation claims alleging that working conditions in a Malaysian factory were unsafe and exploitative. Tesco, meanwhile, is dealing with a class-action lawsuit brought by workers at a Thai factory that made garments for its F&F brand until 2020, and a number of carmakers are dealing with difficult questions about cobalt mining.

Companies have long been aware that the blowback from ESG-related failures in supply chains can eviscerate reputations, incur fines, trigger lawsuits and, in the most severe cases, end operations entirely. As consumers become more ethically conscious and regulatory bodies strengthen their rules, the stakes are rising. How, then, should companies communicate their ESG due diligence and if the worst-case scenario arises where an ESG-related failure is discovered in the supply chain, how should they respond?

Never hush up a problem

“Transparency and honesty are crucial,” says Helen Ellis, head of consulting at Team Lewis, a marketing and communications agency. “It’s important to own a mistake. Ultimately, it comes down to trust and honesty; it’s about trying to very quickly say, ‘Yes, this has failed’. Then it’s about communicating and explaining what you’re going to do differently going forward.”

Alex Harrison, co-head of projects and energy transition at law firm Akin Gump, agrees. “It’s not the crime, it’s the cover-up. At its heart, ESG is about integrity. A company that discovers a supply chain issue should look to be as open and honest as it can be about the problem.”

But Harrison counsels against rushing out a statement, beyond acknowledging the problem and a willingness to respond to it appropriately. “A company may not have all the facts, or its suspicions may be disputed or unfounded… the company may not be free to disclose all the information available to it for legal or regulatory reasons.” Instead, a balanced account of what a company does or doesn’t know (and is able to share), may be the best approach; what’s paramount is not burying one’s head in the sand.

Transparency and honesty are crucial. It’s important to own a mistake

How to communicate your next steps

Perhaps more important than acknowledging and communicating about the incident itself is the action that companies take afterwards – and how that is communicated. For instance, the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh, where an eight-storey building housing five garment factories collapsed, was a major turning point for not just one company, but for the whole fashion retail industry.

Companies banded together to create associations coordinating their efforts to address the problems highlighted by the incident. Some of the measures taken included overhauling supplier auditing practices, including broadening the scope of what was included in an audit to cover, for example, the safety of factory infrastructure and workers’ rights. Companies also started to invest more in their suppliers, transforming a purely transactional relationship into a more collaborative one.

Talking publicly about the steps you’re taking to improve, then, can be a good response in the weeks, months and even years following an ESG scandal in your supply chain. After all, the questions won’t stop once you’ve made a commitment to improve: companies will face scrutiny on whether they have followed through.

Take the Boohoo example. “Boohoo quickly sought to rebuild consumers’ trust,” says Ryan McSharry, UK head of crisis and litigation at international PR firm Infinite Global. “It launched a QC-led investigation of its supply chain, hired an independent factory auditor and announced the creation of its own ‘model factory’ that would demonstrate best practice in terms of workers’ rights.”

A 2022 report highlighted progress in Boohoo’s work on its supply chain in terms of sustainability and ethical compliance. But two years on from the scandal breaking, activists and shareholders are still criticising the company for alleged low wages, and the lack of repayment of historically underpaid wages.

Transparency isn’t a silver bullet

Some brands attempt to get ahead of supply chain-related accusations through complete transparency. But clumsy messaging can result in accusations of hypocrisy. When the self-billed ethical brand Tony’s Chocolonely publicised 1,701 incidents of child labour in its supply chain, it claimed that this openness was supportive of its aims of discovering and eradicating child labour and slavery in its business. Instead, the revelation resulted in criticism, such as from Ayn Riggs, founder of Slave Free Chocolate, who said that Tony’s was “pitching virtue to consumers” while engaging in bad practices.

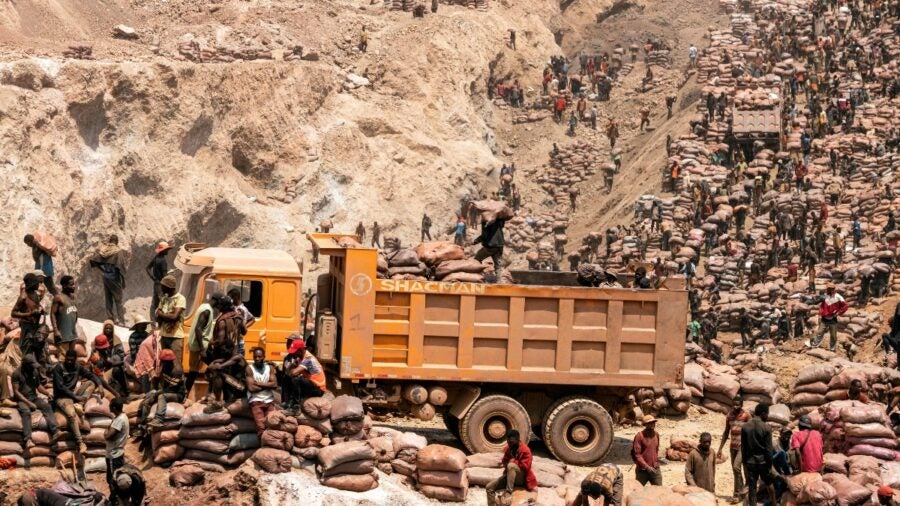

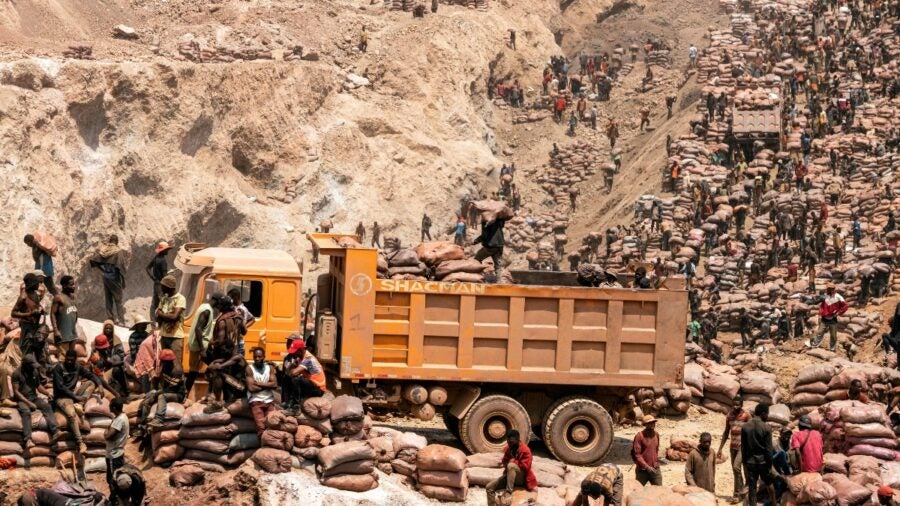

But transparency can only go so far. Mercedes-Benz has published information about its sourcing of cobalt – the element used in electric vehicle (EV) batteries – which is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) under conditions which often violate human rights guidelines. The company has claimed to be committed to the goal of only using “certified” mining sites that have undergone auditing, but in practice it is incredibly difficult to avoid this problem when buying cobalt from the DRC. Tesla has pivoted to focusing on the production of cobalt-free lithium batteries – although this appears to be largely driven by financial rather than ethical concerns.

Building regulatory pressure means that beyond the PR risks, companies also need to think about the legality of their business practices. “It’s an area where the risks for corporates are increasing substantially,” says Richard Reichman, a partner at law firm BCL.

Although the regulatory requirements around this are fairly soft in the UK right now, they are hardening, says Reichman. The Modern Slavery Act and the Environment Act are both being strengthened regarding supply chains. Other jurisdictions are going even further. France has introduced a Corporate Duty of Vigilance Law that requires companies to identify and prevent harm to human rights and the environment in their business practices. And now the EU looks set to follow suit in strengthening its rules, says Reichman.

“It’s crucial to implement and review due diligence procedures to respond to the increasing risk,” he advises. Get the comms right too, and there’s an opportunity for brands to stay on the right side of that threat.

When Boohoo was accused of modern slavery in 2020 because of the working conditions in one of its suppliers’ factories in Leicester, its share price tumbled by 18%, retailers dropped the brand and it faced the possibility of a US import ban. The case was an object lesson in the importance of supply chain due diligence – and handling the communications around it effectively.

Boohoo is far from the only high-profile UK firm to have been caught up in a scandal affecting a supplier. Dyson is facing compensation claims alleging that working conditions in a Malaysian factory were unsafe and exploitative. Tesco, meanwhile, is dealing with a class-action lawsuit brought by workers at a Thai factory that made garments for its F&F brand until 2020, and a number of carmakers are dealing with difficult questions about cobalt mining.

Companies have long been aware that the blowback from ESG-related failures in supply chains can eviscerate reputations, incur fines, trigger lawsuits and, in the most severe cases, end operations entirely. As consumers become more ethically conscious and regulatory bodies strengthen their rules, the stakes are rising. How, then, should companies communicate their ESG due diligence and if the worst-case scenario arises where an ESG-related failure is discovered in the supply chain, how should they respond?