From politics and population to the environment, the water industry is facing greater and more varied challenges than ever before. Population growth is particularly pressing, with the UK population projected to increase by 9.7 million to 74.3 million in mid-2039. Compounding this is the increase in single-occupancy households, which tend to use twice as much water per head than a property with four people.

Added to these pressures, water companies around the country are likely to continue to see their revenues restrained, as seen in the 5 per cent average reduction at the 2014 price review, while there is a growing requirement to provide customers with a better service, protect the environment and consider the needs of society as a whole, still satisfying other stakeholders.

According to a number of industry thought leaders, such as AECOM, a fully integrated global infrastructure firm that advises a number of the largest water companies in the UK, to meet these challenges the water industry needs to think beyond purely financial considerations.

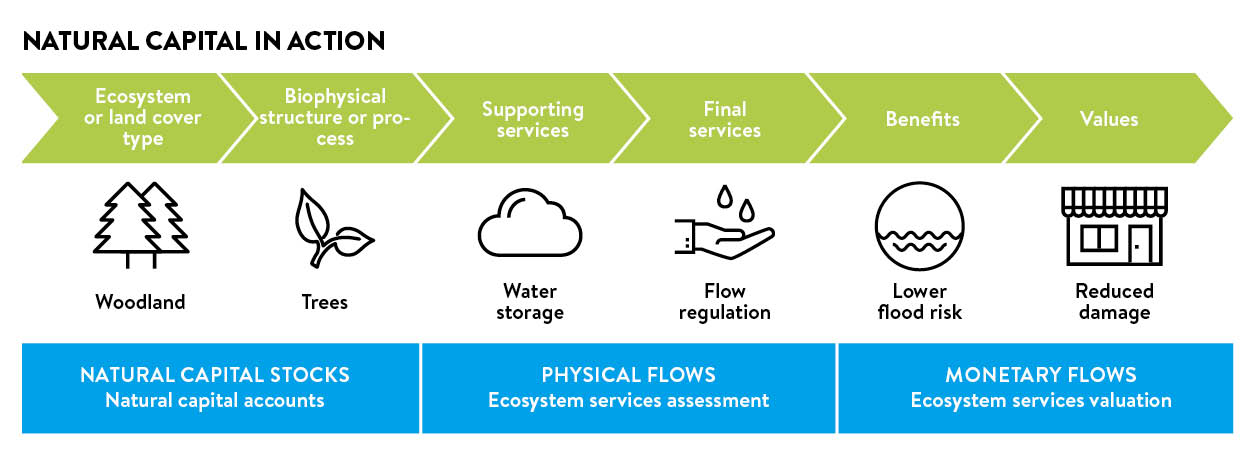

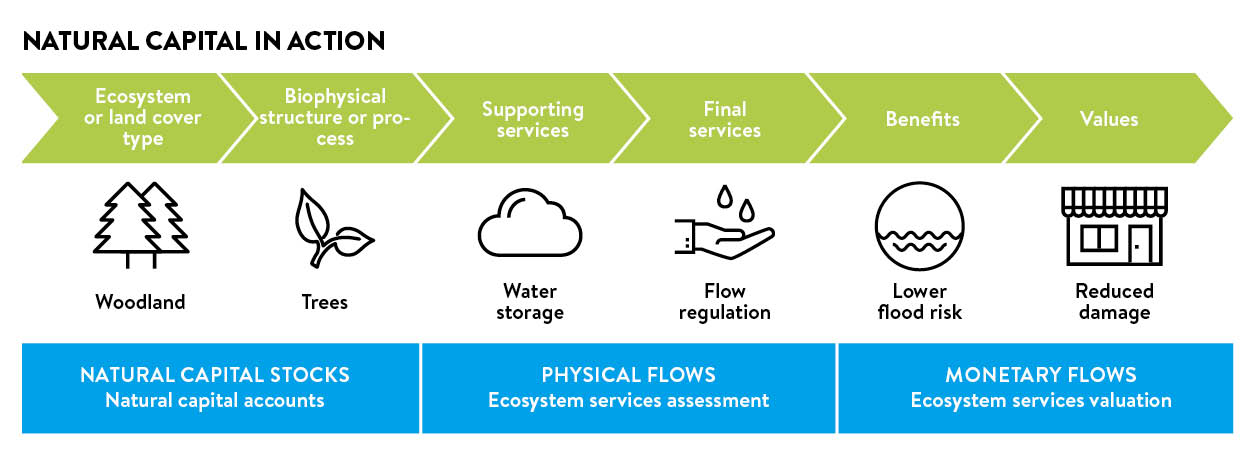

“The industry is doing a lot, but it needs to become more forward looking,” says Martin Williamson, government and public sector lead for water at AECOM. He argues that water companies need to consider natural, human and social capital, as well as financial, in their business planning. “These other capitals have been around for some time, but people have sometimes struggled to include them in their business cases. By making use of monetised values, which are becoming more accepted now for these other forms of capital, the leaders in the sector can realise long-term benefits that provide not only medium-term solutions, but a long-term legacy. Invest now and you will see the outcomes.”

Thinking beyond just the traditional financial-capital model and exploiting natural, social and human capital is helping to build a more sustainable, more financially secure water industry

An adviser to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) on ecosystem services, AECOM also leads the Natural Capital Coalition’s operations group focused on the practical application of the Natural Capital Protocol.

Mr Williamson’s colleague Adrian Rees, director of asset management for water, offers an example of these other capitals in action: “Installing a sewer will prevent flooding and that will have an immediate effect. However, you could opt instead for a more sustainable drainage system that creates more green spaces and provides activities and involvement for local people. This has much wider benefits – natural, social and human capital. Anglian Water, for instance, is quantifying the social benefits of its volunteer programmes in beach and river care.”

Employing natural capital requires longer-term, more holistic thinking. “You might have a water treatment works that’s treating discoloured water to remove discolouration,” says Mr Rees. “One of the reasons for that discolouration will be runoff from peaty catchments. So if you use a number of techniques to manage those upland catchments, you reduce the discolouration and you reduce your capital and operational expenditure by not having to treat that water as intensively. But you also get collateral benefits because the flow from those uplands is slowed and so downstream areas are less prone to flooding.”

A catchment management approach can take a while to bed in and produce returns, but Defra, water services regulator Ofwat and others are encouraging it, whereas in 2004 there was just one example of sustainable catchment management in companies’ plans – United Utilities’ SCaMP project – ten years later there were more than 600 actual or potential schemes put forward to Ofwat.

Already some water companies are making changes to their structure to embrace natural, social and human capital. “Engineers aren’t environmental economics specialists and why would they be?” says Adrian Rees. “But we provide tools that in essence tell them ‘if you do this you’ll attract these benefits’. For example, at Yorkshire Water’s Rivelin Water Treatment Works, we’ve been able to show the economic benefits of partially burying the plant and incorporating a green roof in terms of natural and social capital. They’re applying this thinking to every investment decision across thousands of their assets – you can imagine the benefits this will generate.

“You need buy-in at senior stakeholder level. Yorkshire Water has the advantage that the finance and regulation director sits on the Accounting for Sustainability board and the Natural Capital Coalition board.”

Alongside this the human and societal elements require a change in customer behaviour and companies need to take a lead here, for instance, by reminding customers that foreign objects thrown down toilets lead to costly blockages. “It’s about using social and human capital available to them to deliver a financial capital benefit,” says Mr Williamson.

A growing number of water companies are appreciating the need to deliver more with less, not so much as a challenge, but as an opportunity. Thinking beyond just the traditional financial-capital model and exploiting natural, social and human capital is helping to build a more sustainable, more financially secure water industry.

For more information please visit www.aecom.com

SLUDGE ONCE UNWANTED IS NOW CREATING ESSENTIAL CAPITAL

Once unloved and unwanted, sludge is offering new and exciting examples of the circular economy at work. It’s long been a problem for water companies, but is now creating essential capital.

A new technology called thermal hydrolysis, which works like a huge pressure cooker, prepares the sludge so you can get increased production of methane from it. This also reduces the amount of solids that need to be disposed of.

“In a recent project we saw an increase in methane of 40 per cent over the traditional process – this biogas can be used as a renewable energy source, providing energy to power the treatment plant, making it almost cost neutral,” explains Steve Baker, utilities sector lead for water at AECOM.

“Fewer solids mean that you’re transporting less waste products which means fewer lorries. We can also look at removing phosphorus and using it in fertiliser. There’s even the possibility of removing precious metals from it. This is the circular economy and natural capital in action.”