As an innovation born of the 20th century, much of the UK’s current nuclear infrastructure is now in need of urgent attention. Cold War haste and a desire to spearhead the nuclear revolution meant that little thought was put into how these facilities would one day be decommissioned. This has left the UK with a number of sites that demand a carefully considered approach to deconstruct and remove the remaining hazardous waste safely.

As an innovation born of the 20th century, much of the UK’s current nuclear infrastructure is now in need of urgent attention. Cold War haste and a desire to spearhead the nuclear revolution meant that little thought was put into how these facilities would one day be decommissioned. This has left the UK with a number of sites that demand a carefully considered approach to deconstruct and remove the remaining hazardous waste safely.

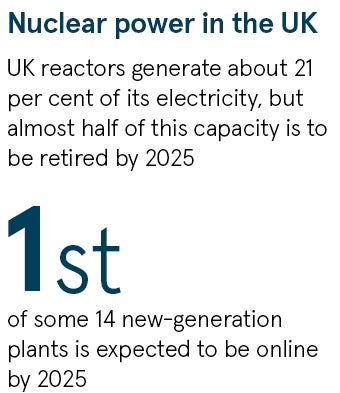

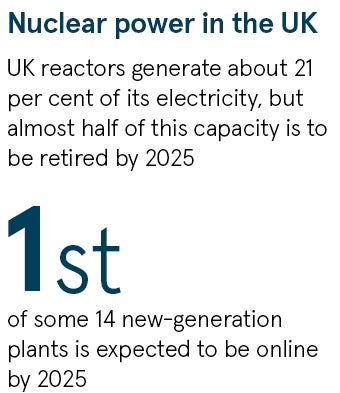

The nuclear challenge only becomes more complex when factoring in our 21st-century lifestyle expectations and energy needs. Many nations are now looking to phase out the use of fossil fuels permanently, yet energy demand surges due to population growth and increasing electrification. This has led the UK government to conclude that nuclear power should form part of the nation’s future energy supply mix as it strives to reduce carbon emissions.

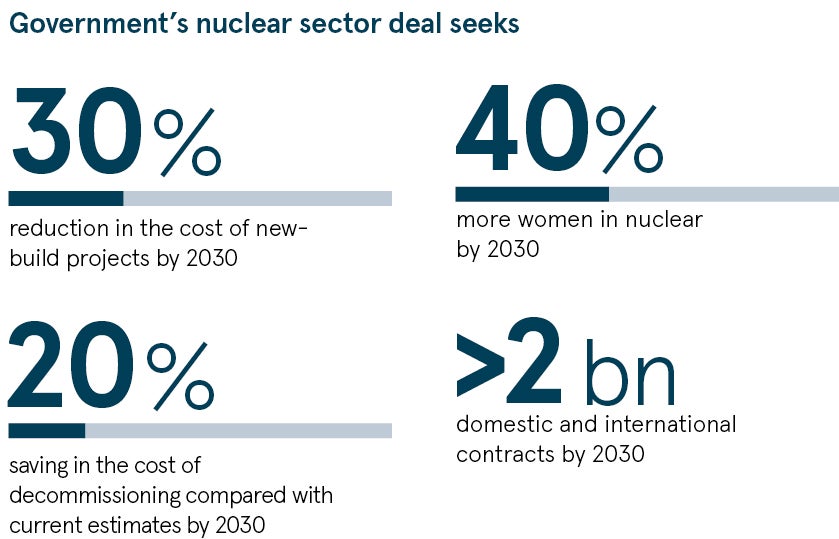

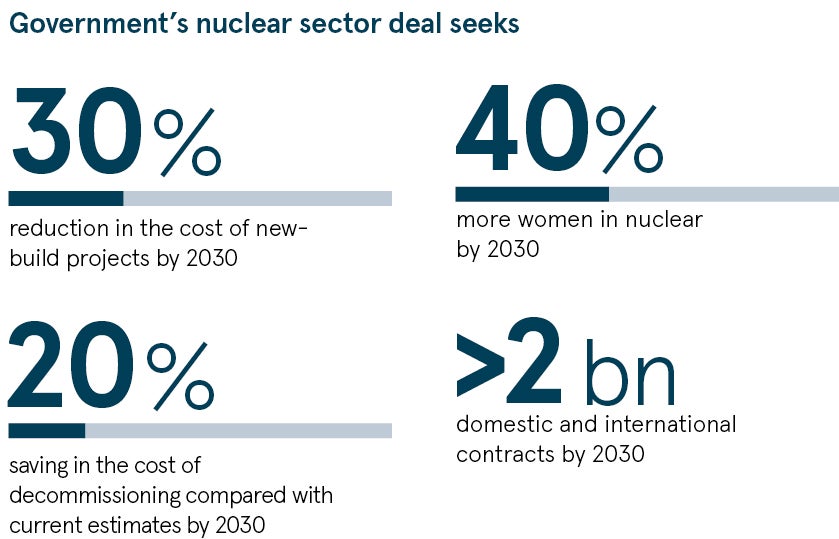

Through its Nuclear Sector Deal, the government seeks to achieve a 30 per cent reduction in the cost of new-build plants and 20 per cent savings in decommissioning costs compared with current estimates, all by 2030.

This ambitious nuclear renaissance, however, hinges on a sector with a reputation for overspending, poor scheduling and unnecessary complexity. These problems are compounded by the UK’s generational gap in nuclear plant construction, with the last new build having been completed decades ago. This fallow period has reduced the nation’s supply chain, furthering its inability to complete projects on time and on budget.

Yet there can be little doubt that nuclear energy provision is still incredibly complicated, even for nations and developers that have the benefit of hindsight. New-build plants in Europe and the United States are experiencing severe delays and cost overruns, with power now expected to be generated several years behind schedule.

Irrespective of this apparent global tussle with nuclear programmes, our collective need for nuclear power continues apace. As such, we must address the hugely complex risks associated with legacy infrastructure and, for the UK especially, improve our delivery of new-build construction to keep the lights on at a cost we can afford.

If the aim is to save time, money and gain parity on the international stage, as the Nuclear Sector Deal highlights, then there is an urgency for innovative management expertise and collaboration to secure a lasting shift in the reliability of domestic nuclear projects. But what does this look like in practice?

Eliminate over-engineering

As decommissioning programmes are growing in scale and complexity, a cultural shift is needed to recognise that methods and processes designed for long-term operations are inappropriate for short-term projects.

For some time now, the nuclear industry has tended to over-engineer bespoke solutions to every problem rather than draw on commercially available products. More than this, every component will be designed to the highest integrity levels irrespective of its purpose. A drainage pump, for example, will not just be designed to function within its set delivery period, but for decades after its intended life. This propensity to gold plate is not just time and resource intensive, but also entirely unnecessary.

Some will quite rightly point out that in an arena where safety is paramount, the need for meticulous detail can only be a good thing. While it’s true that mitigating risk is always the top priority for nuclear, it’s undeniable that our approach is often overly cautious, even for non-critical components that have no contact with radioactive material. Providing a device is capable of functioning safely, it makes little sense to pursue the perfect design for a job that has imperfect requirements. Using tools and devices that are fit for purpose, and not ones for every purpose, will ease pressure on the supply chain and help keep finances and deadlines in check.

Modernise processes

Far from being an obstacle to success, the UK’s unfamiliarity with modern nuclear construction gives it an opportunity to update its processes and lead from the front. While each nuclear facility presents its own unique set of challenges, there is still much that can be learnt from commercial processes outside of the sector.

In constructing multiple oil and gas platforms in the Caspian Sea, and in constructing accommodation for the British Army throughout Aldershot and the Salisbury Plain, standardised designs and modularisation techniques have assured success on a large scale. In these multi-billion-pound programmes, manufacturers are engaged at the earliest stages to ensure that designs are realistic against the requirements, timeframe and budget set. In many cases, digital twins – computerised visualisations of physical assets and processes – are also used to assure certainty before arriving on site.

These designs are then frozen before construction starts, avoiding abortive work, and standard solutions mean that many activities and modular facilities can be replicated to reduce cost. This approach has driven double-digit percentage savings in the time taken to complete repeatable facilities.

Of course, these examples are not entirely comparable as nuclear is subject to highly rigorous regulation, but the general principles still apply. So long as safety is accounted for, programme management successes in other areas can be treated as solid guidelines for a more effective UK nuclear industry.

Collaborate

Finally, it’s critical to reaffirm the importance of a joined-up approach where all parties co-operate to manage project risk, share in the rewards, and combine talent to support supply chain growth and deliver economic benefit to local communities. An open book approach not only helps the numerous organisations involved in these large-scale projects to work more productively, but also reduces the tendency for companies to retreat behind contractual small print when things go awry.

The Nuclear Sector Deal stresses that time is very much of the essence. It’s therefore essential for the sector to adopt a collaborative mindset as it re-establishes itself in the 21st century. The nuclear sector is an exciting place right now and by building on the lessons from other sectors, we have the potential for the UK to take a leading role in this global market.

For more information please visit www.kbruk.co.uk/nuclear