A disease can be defined as “rare” when it affects fewer than five in ten thousand people. In the UK, this means that an estimated 3.5 million people will have a rare disease at some point in their life.

The number of medicines being developed and approved in Europe for treating rare diseases is on the rise, which is also increasing the volume of applications for funding on the NHS across the UK.

A number of funding bodies around the UK are tasked with assessing whether new medicines represent good value for money for taxpayers and should be funded for use by the NHS. In cash-straitened times, these are not easy decisions to make. However, assessing the “value for money” of medicines developed for small groups of patients has a number of innate challenges which these bodies are attempting to address.

Scotland and Wales have recently amended their reimbursement processes for rare diseases. One key change emphasises the importance of both the patient and the clinician’s experience in living with, or treating, rare conditions which decision-makers may often not be familiar with. The assessment processes also take into consideration the issues around interpreting data which can only be derived from small patient populations.

Whereas in England the assessment for the funding of medicines to treat rare diseases is fragmented, with a number of possible processes split between two decision-making bodies, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) or NHS England.

When a medicine is assessed by NICE, there are two main mechanisms for consideration of rare conditions. Firstly, the same technology appraisal process used by NICE to assess conditions with larger patient numbers can be applied. This can be problematic when looking at medicines to treat much smaller patient numbers as cost effectiveness, which NICE assesses, can be difficult to quantify. Secondly, the Highly Specialised Technologies programme, which was specifically designed for small patient populations of around 500 or fewer across the country, can be used. This programme was developed following recognition of the challenges inherent in the standard NICE processes being used for assessment of medicines in conditions with very small patient populations.

Being able to access medicines that help to slow the progression of pulmonary arterial hypertension is of the utmost importance

Medicines with a positive recommendation for use on the NHS by NICE will be funded, by law, centrally by NHS England.

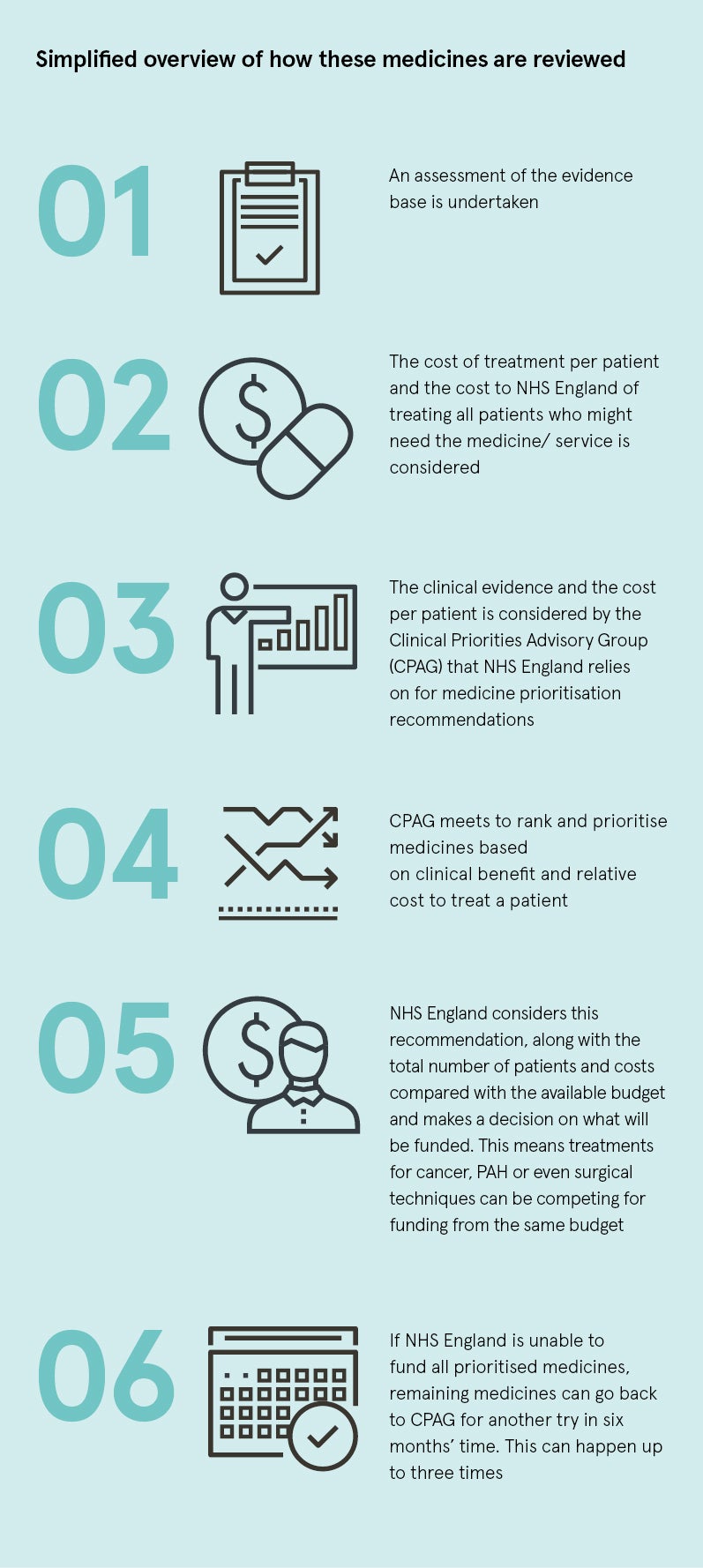

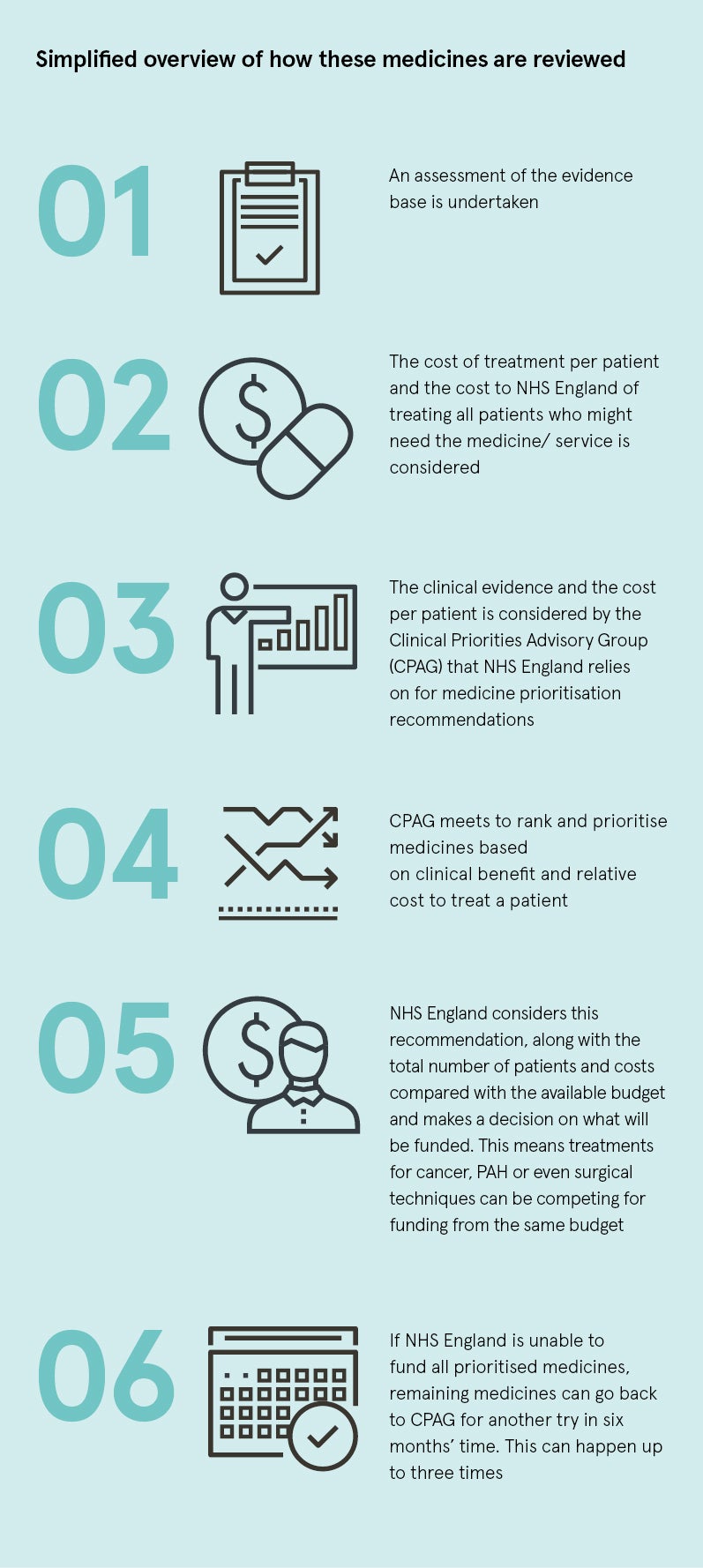

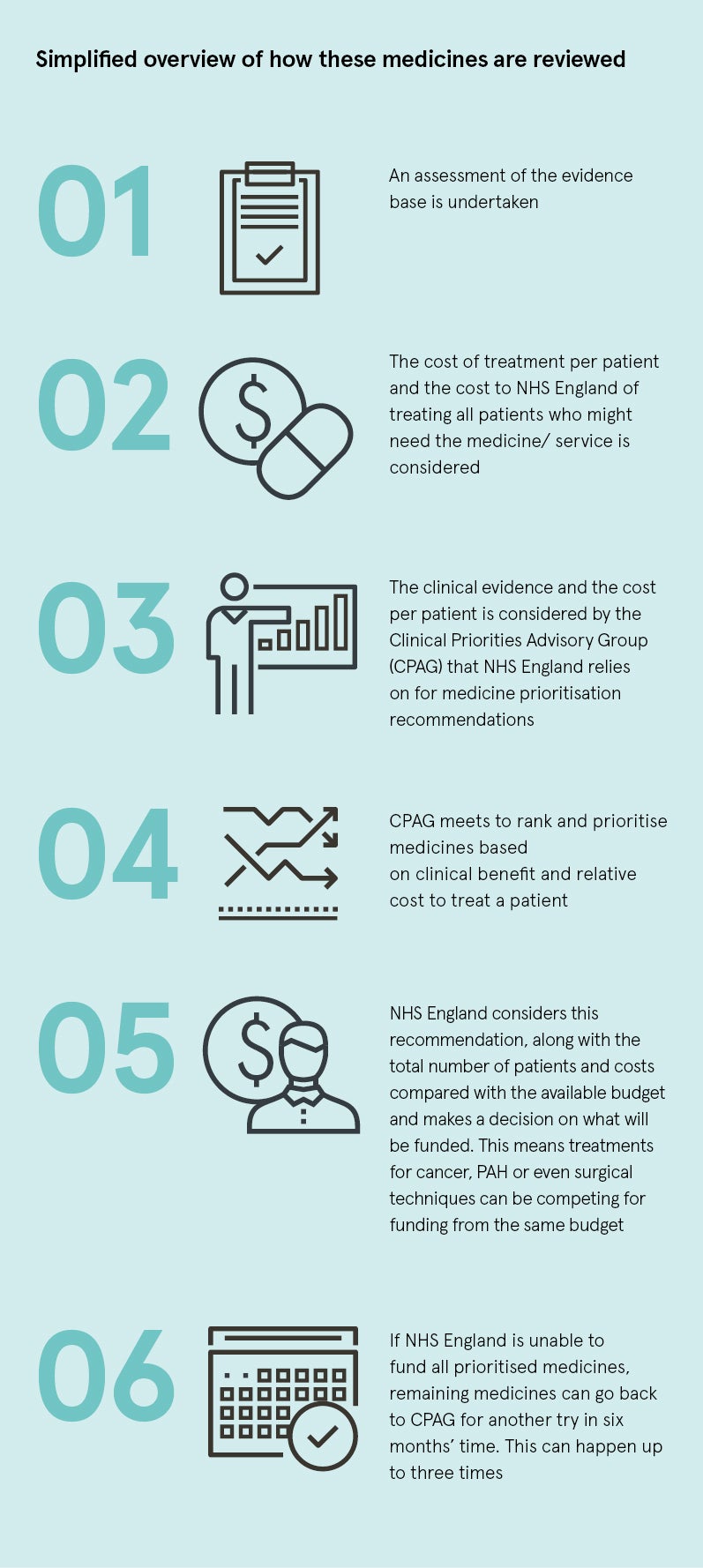

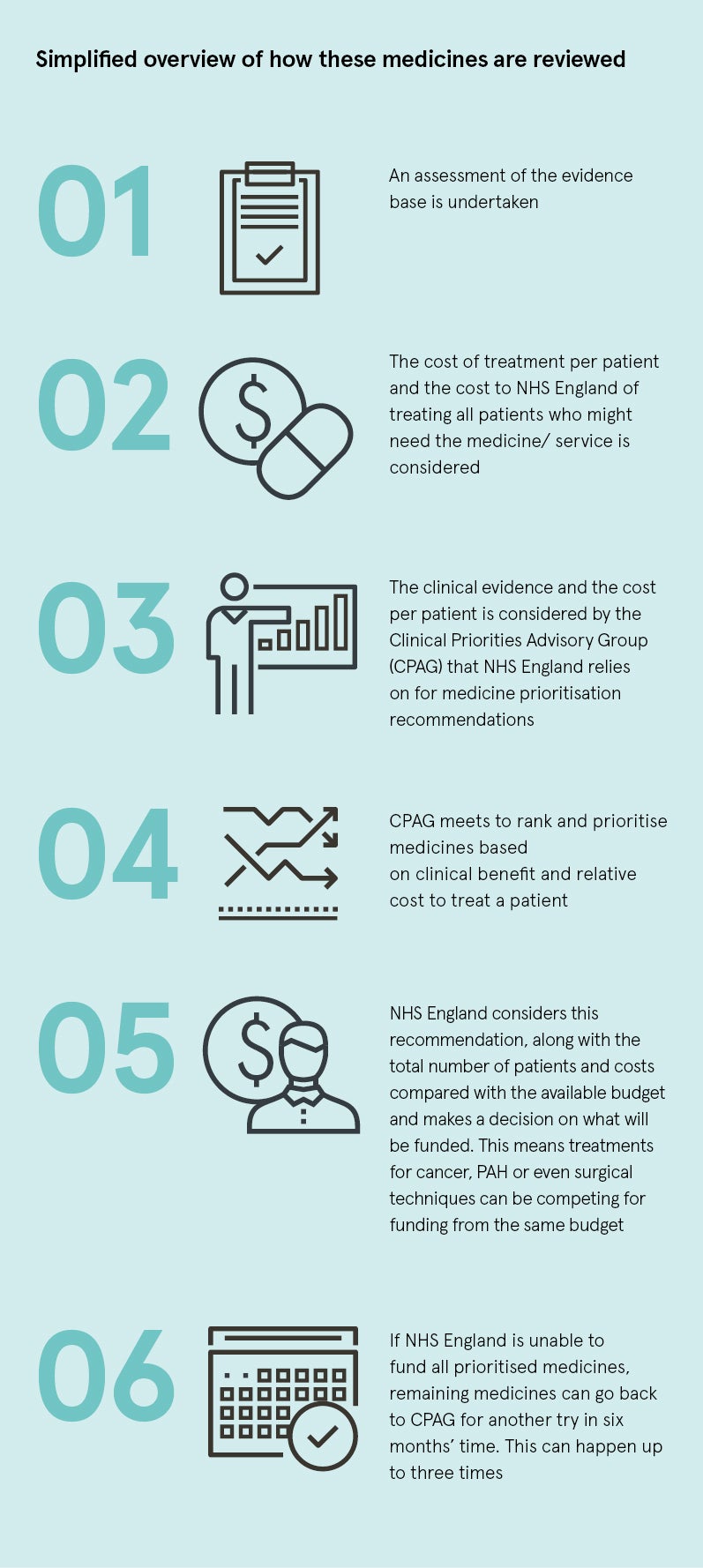

However, not all medicines for rare conditions meet the criteria to be assessed by NICE; these medicines are directly assessed and considered for funding by NHS England. In addition to medical devices and service developments, they are entered into a prioritisation process that takes place twice a year.

This year, NHS England had a total budget of £17.7 billion for the funding and delivery of specialised services, which are provided to people with relatively uncommon and complex needs. After prioritising a number of other statutory commitments and obligations, NHS England allocated a budget of £25 million to new interventions being considered in the prioritisation process. With a limited budget, NHS England then prioritises these new interventions to decide what it might be able to afford.

NHS England uses different methods to NICE; a simplified overview of this process is outlined in the graphic.

The outcome is not, therefore, inherently based on the added benefit to patients or cost effectiveness and ultimately some patients will miss out.

Challenges facing the PAH community

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is an incurable and progressive illness, which ultimately causes right-heart failure and death. Breathlessness is the most frequent symptom, at first occurring with simple everyday activities such as climbing the stairs, and eventually patients can struggle to breathe even at rest. Left untreated, the prognosis is poor with an average life expectancy after diagnosis for some types of PAH of two to three years, worse than survival rates for some common advanced cancers.

Being able to access medicines that help to slow the progression of the disease is of the utmost importance, as it allows patients to live as normal a life as possible for longer, which is vital for a patient with a life-limiting disease.

In England, PAH medicines are considered for funding via NHS England’s prioritisation process. Despite demonstrating sufficient clinical benefit to be considered by this process, a PAH medicine failed to secure funding in May as the budget could only fund treatments in the first three of five priority bands.

This decision has created a disparity in access across the UK as eligible NHS patients in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales are now able to receive treatment with this medicine. It has created the situation where patients from Wales are treated in specialist centres in England, while patients residing in England are not yet able to access treatment with this medicine through the same centres.

Commenting on the reimbursement process challenges of the prioritisation process, Dr Jayne Spink, chief executive at Genetic Alliance UK, says: “The series of opaque and seemingly illogical decisions made in the allocation of funding to decision-making processes for rare disease treatments in England are demonstrably inequitable. A more strategic, consultative and transparent approach is called for.”

Improving care for PAH patients

A key part of addressing the unmet needs of people with PAH is ensuring all patients with rare diseases get fair and equitable chances of access to innovative new medicines. This may require reconsideration of the various assessment and funding mechanisms in England. In particular, NICE needs greater capacity to evolve its methods so it can appropriately assess more medicines for rare, and not just some ultra-rare, conditions.

With a vision for a normal life for people with cardiopulmonary disease, Actelion has a long-term goal to transform PAH into a chronic and manageable disease. We should all work together to ensure patients get timely access to innovative and beneficial treatments for all rare diseases, which often have devastating consequences for patients and their families.

SEL 18/0195

September 2018

Being able to access medicines that help to slow the progression of pulmonary arterial hypertension is of the utmost importance