Before any medicine can be made available to patients, it must undergo rigorous regulatory scrutiny, over a number of years, proving both its efficacy and relative safety. With common conditions, such as arthritis, colorectal cancer or hypertension, this rapidly becomes an exercise in managing big data. However, for the class of conditions considered “rare”, this is far from the case.

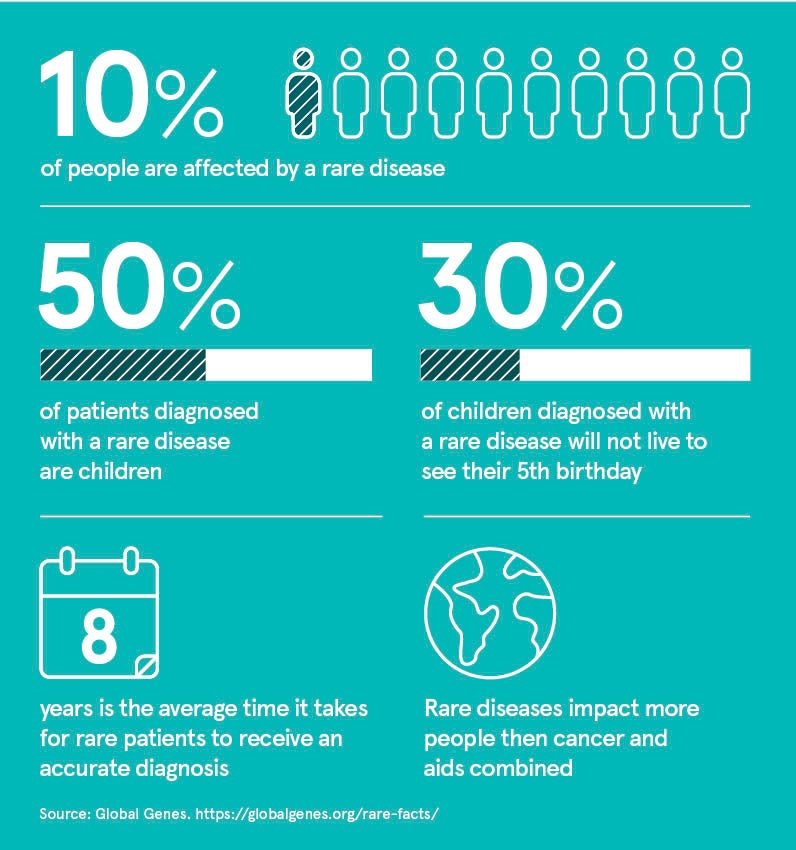

While 7,000 rare conditions affect more than 400 million people globally, who could form the world’s third most populous country, individually each condition has relatively few sufferers and developing treatments is consequently very difficult.

Lack of therapies for most rare diseases is an unacceptable reality for millions, with treatments only existing for 5 per cent of such conditions. Rare conditions mainly affect children, most are genetic in origin and three out of ten children born with a rare disease will not live to see their fifth birthday. The positive news is there’s a surge in interest to find medicines driven by new technology and scientific advancements, but issues exist.

The medicines of tomorrow are utterly dependent on the goodwill and hope of patients today

“The extraordinary challenge is that each rare disease affects a small number of patients. They are often frequently misdiagnosed. If new life-saving medicines are to enter clinical trials, it’s vital to engage with patients and multi-disciplinary medical professionals to fully understand their condition inside out,” explains Fabrice Chartier, chief operating officer of Simbec-Orion, a leading global, full-service clinical research organisation with a rare disease focus.

“The medicines of tomorrow are utterly dependent on the goodwill and hope of patients today, without their altruism and dedication we could not develop new medicines.”

It doesn’t help that those suffering from rare diseases are hard to find, they often have debilitating conditions and are geographically dispersed, many also have a limited ability to travel because of their ailment. Many are very young, which means taking part in clinical trials requires the consent of guardians, as well as their assistance; the odds are stacked against developing treatments.

“It takes a lot of experience when developing and managing these clinical trials. You need sensitivity, skill and expertise, especially in paediatrics,” says Dr Chartier, whose company has dedicated 23 years to this sector. “Regardless of the condition, this needs to be fully understood and catered for. We’ve even created comic book-style information packs to help engage younger patients.

“We are passionate about making trials as patient friendly as possible. We work with biotech companies developing new medicines to ensure all studies are patient centric, home based where possible or have travel organised to the hospitals involved and ensure the tests being measured are appropriate for the patients. We want to reduce disruption by bringing the study to the patient.”

One of the biggest issues with rare diseases is they do not benefit from the economies of scale that drug development relies on with more common conditions. It’s the reason why so-called orphan drugs must be developed with a frugal approach.

“This is not ‘big pharma’. The needs of smaller biotechnology companies are different. We have to be budget conscious, yet super-effective.

It often involves thinking outside the box, offering bespoke, modular and adaptive clinical trials,” says Doug Cookson, chief marketing officer at Simbec-Orion.

“We also have to be agile hence our lean, flat operational structure with hands-on senior management. We manage the whole clinical development process, allowing our clients to focus on the medicine,” says Mr Cookson, whose firm enrolled more than 3,500 rare disease patients in 34 countries on four continents in the last five years.

Rapid advances in science are transforming the treatment of rare diseases with an increasing number of promising drugs in development. “We’re going to be able to treat many more conditions, that’s why we are passionate about engaging with patients now about the value of their contributions,” Dr Chartier concludes. “The development of a new treatment for another life-threatening, rare disease could be just one trial away.”

For more information please visit www.SimbecOrion.com