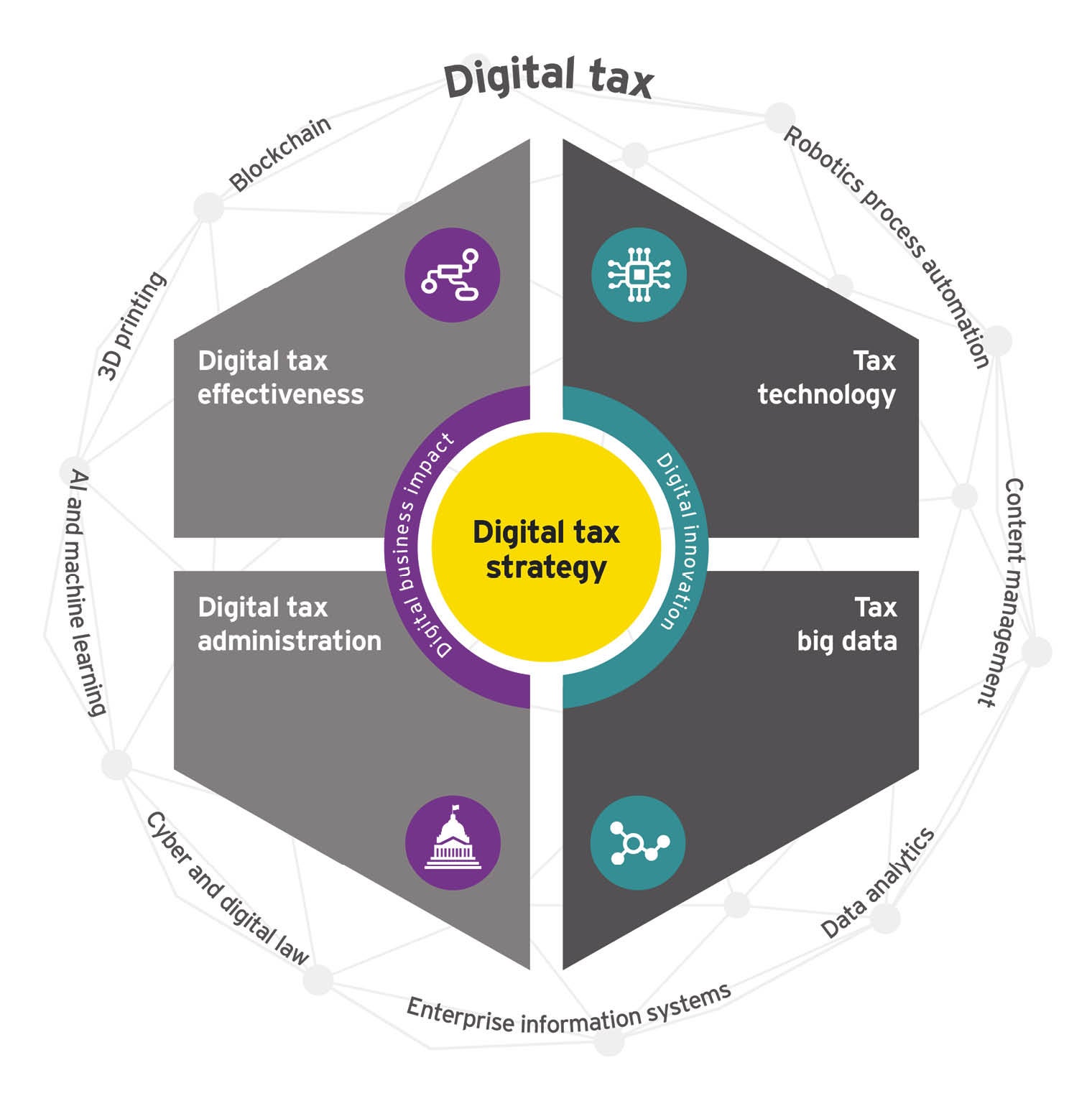

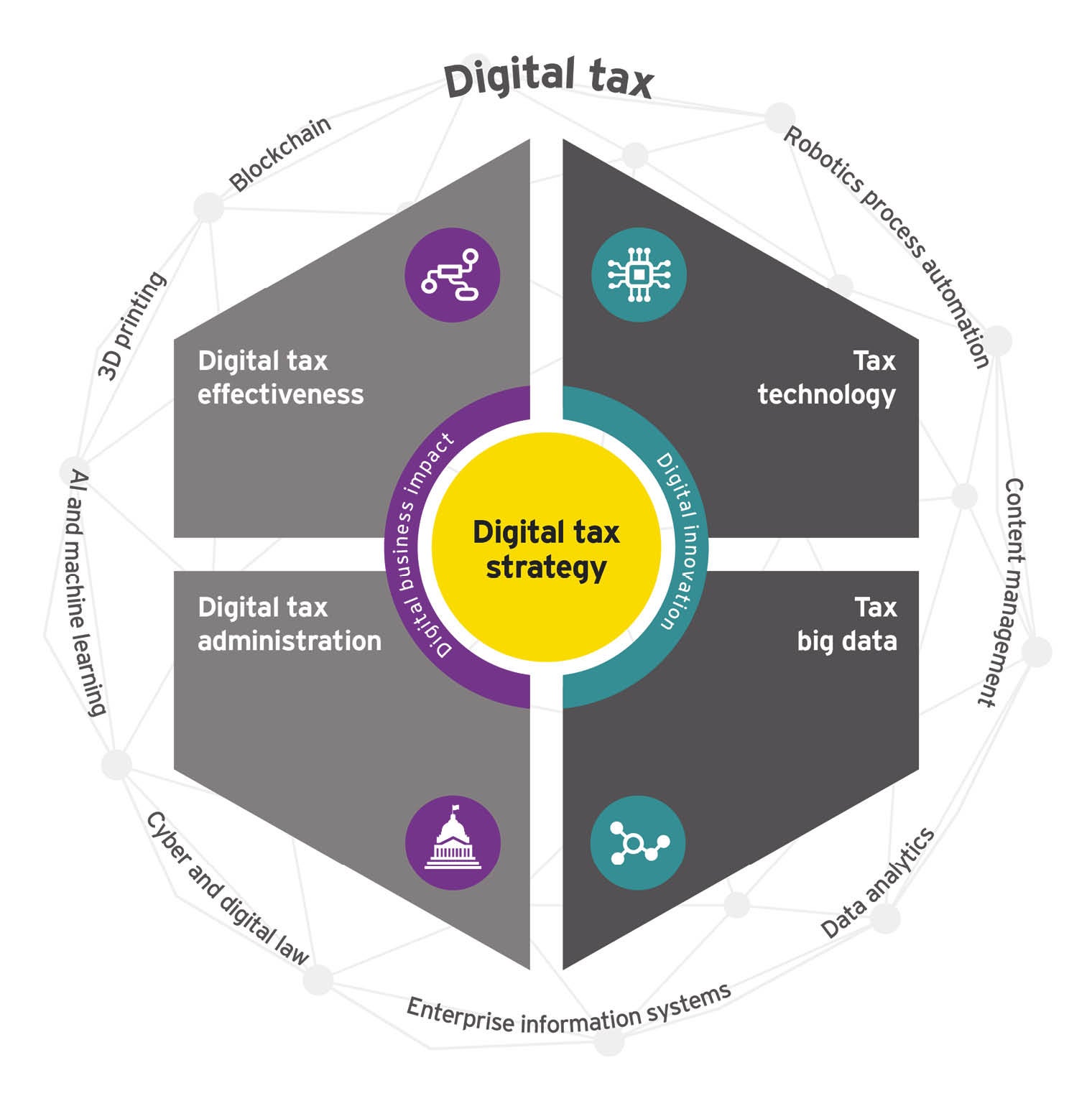

Having long been regarded as essential but rarely at the cutting edge of new technology, tax departments and tax authorities are suddenly undergoing enormous change as digital technology revolutionises the way they operate.

Digital technology in tax is rapidly moving up the boardroom agenda as it affects organisations both internally and externally. As businesses become more digital, governments and tax authorities are having to change the way they collect taxes. As the tax authorities themselves also adopt disruptive technology, including advanced data-driven auditing techniques, they’re forcing organisations to respond.

Meanwhile, organisations’ finance and tax functions are using recent advances in technology to improve management of their tax affairs and obligations. They’re taking advantage of robotics process automation and machine-learning applications to improve greatly the accuracy and efficiency of their accounting and tax compliance activity, while at the same time achieving a significant reduction in costs. Leading organisations are also extending their big data strategies to the world of tax, using real-time analytics to understand both their global tax position and how they manage their tax risk more effectively.

The speed of change is accelerating, particularly as tax authorities adopt disruptive technology, so it is imperative that businesses are in a position to respond

“We’ve seen an explosion of new technology over the last six to twelve months alone,” says Tim Steel, UK and Ireland tax markets leader at EY, a global leader in assurance, tax, transaction and advisory services. “Digital transformation in tax is moving up the boardroom agenda rapidly because it’s no longer an option – companies need to get ready for it now. As well as technology, another big driver for boards is cost. Organisations are under cost pressure and the use of these disruptive technologies is a great way to drive down costs.

“In the past, tax has often seemed to lag behind other areas of the finance function, so tax professionals need to ensure that their department keeps pace. They also need to get ready because of the digital transformation of tax administrations worldwide.”

Tax authorities around the world are investing in new technology and developing new capabilities that allow them to look at taxpayer data in a new way. This presents a challenge for corporate taxpayers since authorities now demand more data and they want it quicker than ever.

“There’s a move towards real-time reporting,” says Charles Brayne, UK and Ireland digital tax leader at EY. “A growing number of tax authorities are moving away from periodic, summarised filings in favour of much more extensive data requests. If, as an organisation, you can’t satisfy these increased demands by the authorities, you’re more and more likely to be subject to investigations and possible fines.”

Financial services as a sector has been at the sharp end, driven by the demand for increased transparency and reporting responsibilities. Banks and other financial institutions in particular have been forced to invest in their digital capabilities.

In the UK, HM Revenue & Customs has a stated ambition to make tax digital by 2020, but other countries around the world, including Mexico, Brazil, India and China, are already further advanced in this journey. “The direction of travel around the world is clear – with new technology there is greater capability to analyse taxpayer data more comprehensively, accurately and quickly than ever. UK firms that trade globally are already exposed to these rapid developments,” says Mr Brayne. “They have to keep pace with the fastest-moving territories in which they operate.”

The speed and scope of these changes has caused some businesses to make mistakes as they try to adapt quickly. In particular, they often try to solve problems in isolation.

“You might find, for example, a multinational with headquarters in the UK and offices globally trying to handle the changes in the tax administration in Mexico with a purely local solution and without thinking globally. This means that they can’t scale up or standardise,” says Mr Brayne. “In other cases they simply aren’t aware of the tax requirements globally across their various offices and have little or no understanding of the risks and liabilities they’re exposed to.”

Organisations, Mr Steel says, need to have a clear digital roadmap covering the next three to five years, but they also need to look to identify quick wins in the short term. “We’re working with many companies that are already deploying robotics and artificial intelligence to handle the process-driven activities that are part of tax compliance, for instance making sensible tax decisions about allowable and disallowable items.” EY has built a pattern data machine-learning engine that can analyse thousands of lines of data in a few seconds, learning as it goes.

But with so much focus on technology and machines is the tax professional an endangered species? Not if they adapt, says Mr Brayne. “We’re seeing very different skillsets emerge. Digital tax professionals or tax technologists understand how to standardise processes and embed tax rules within automated systems. They are confident with data and comfortable with the high degree of automation achievable through the latest technologies,” he says.

There are other opportunities as more routine tasks, especially those relating to compliance, are undertaken by machines. Mr Steel adds: “Tax professionals need to move up the value chain. They have to focus on areas that require human judgment and interaction, for example partnering with the wider business and demonstrating their commercial judgment. Rather than just looking at the numbers, their work will be more about innovation, relationship building and providing advice on complex matters, and generally making a greater contribution to the business.”

The tax landscape will continue to become more complex, but technology will handle an increasing amount of this. “Meanwhile tax professionals can become involved in more interesting work,” says Mr Brayne. “Those organisations that use this new disruptive technology effectively will increasingly see the more routine elements of the tax professional’s responsibilities undertaken by machines, allowing them to enjoy the more interesting and challenging elements of the job.”

Mr Steel concludes: “The speed of change is accelerating, particularly as tax authorities adopt disruptive technology, so it is imperative that businesses are in a position to respond.”