Leonardo da Vinci’s sumptuous Portrait of an Unknown Woman, known by its French title La Belle Ferronnière, is one of the proudest possessions of the Musée du Louvre. So far, anyone wishing to see it has had to make their way to Paris, where La Belle lives. Soon, however, the Renaissance lady will be taking up residence for a year in Abu Dhabi, where the Louvre is opening a satellite museum.

For the first time in its history, France is opening outposts of its national museums on foreign soil. As the government earmarks less and less money to culture every year, museums in France, as elsewhere, are having to come up with evermore creative ways to raise funds. Opening offshoots abroad is a path that more than one museum is taking.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi

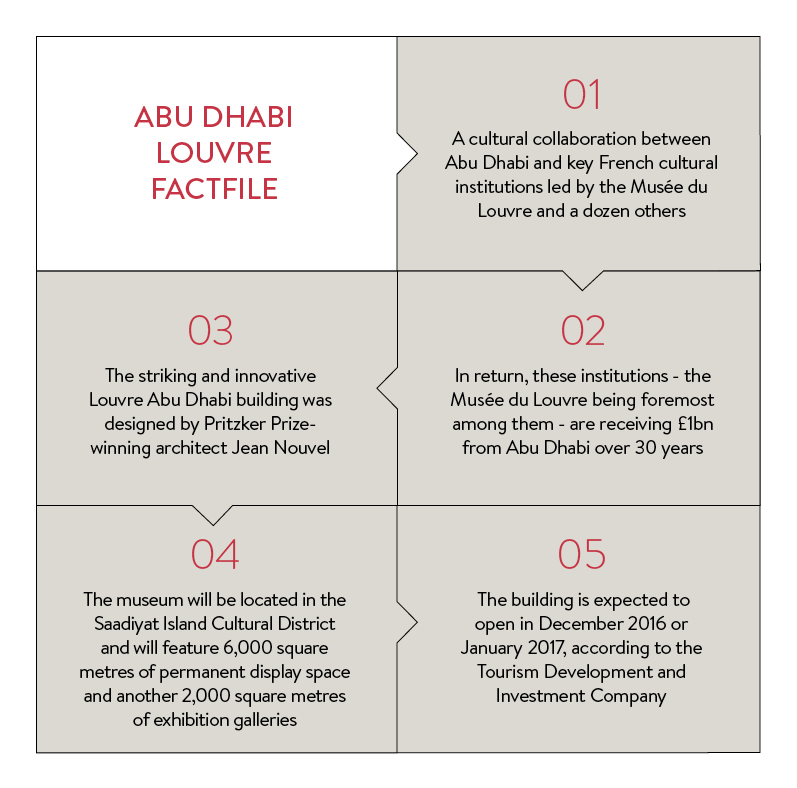

The Louvre Abu Dhabi is the most spectacular example. Following a 2007 agreement between the governments of France and Abu Dhabi, skillfully negotiated by the Louvre’s then general administrator Didier Selles, a consortium of French cultural institutions, led by the Louvre, but also including the Musée d’Orsay, the Pompidou Centre, the Château de Versailles and a dozen or so others, are lending their savoir faire and, for the first ten years, works of art to the nascent Gulf institution.

In exchange, these institutions (the Louvre being foremost among them) are receiving €1 billion (£774 million) from Abu Dhabi over a 30-year period. The money will help open up new wings, manage and maintain collections and buildings, pay for restorations, and buy works.

The Emirates’ version of the Louvre museum is being built on a new artificial Island of Saadiyat in the United Arab Emirate of Abu Dhabi

The architect of the Louvre Abu Dhabi is the Pritzker Prize-winning Jean Nouvel. The building he has designed is recognisable by a vast, discus-shaped dome, with perforations that cast speckled shadows on the ground beneath. With construction now more or less complete, the edifice will soon be handed over to the museum’s administrators, who will get it ready to host the art and the visitors. The date of the opening is yet to be set.

The money will help open up new wings, manage and maintain collections and buildings, pay for restorations, and buy works

Featuring 6,000 square metres of permanent display space and another 2,000 square metres of exhibition galleries, Louvre Abu Dhabi will, in its inaugural year, show 600 works, some borrowed, others acquired. Masterpieces flying over from Paris include not only the Leonardo, but also Edouard Manet’s The Fife Player (1866) and Vincent van Gogh’s Self-Portrait (1887).

Artist’s impression of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, due to open in late-2016

Pompidou Malaga

The Pompidou Centre in Paris already has a foreign outpost up and running. As of March 2015, and for a total of five years, residents of Malaga in southern Spain have had their very own pop-up Pompidou. The mini-museum is housed inside the Cubo, a cultural centre built on the harbour in 2013, where its glass-cube exterior has been given a multi-coloured casing by the French contemporary artist Daniel Buren.

A compressed version of its Paris parent, Pompidou Malaga has attracted a whopping 220,000 people in its inaugural year. On the Malaga menu are 90 works borrowed from Pompidou Paris, including paintings by Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon and Frida Kahlo, and two temporary exhibitions, one of Joan Miro’s works on paper and the other of women photographers of the 1920s and 1930s.

The Pompidou is heading to Asia next with museums planned in South Korea’s capital Seoul and China. There again, economics are a driving force. Pompidou receives a fee of between €1.5 million and €2 million a year from the city which hosts one of its mobile museums, not a negligible sum in these lean budgetary times.

The replication of French museums has not been to everyone’s liking. When the Louvre Abu Dhabi project was first reported, it was met with a ferocious backlash from senior figures in the French museum world. Françoise Cachin, ex-director of the Musée d’Orsay and one-time head of the French national museum authority, teamed up with the Picasso Museum’s ex-director Jean Clair and Professor Roland Recht, of the Collège de France, to publish an irate column in Le Monde.

Selling France’s soul?

“It’s our political leaders who went over to present this royal and diplomatic gift,” the trio wrote of France’s accord with Abu Dhabi. “Isn’t that selling one’s soul?” Ms Cachin and her fellow signatories were adamant that sending priceless artworks halfway around the world posed a grave threat to their safety. They had nothing but scorn for the Louvre Abu Dhabi project.

Another vocal critic is writer Didier Rykner, who edits the online magazine La Tribune de l’Art. When details of the Louvre accord first emerged, he started an online petition against Louvre Abu Dhabi that drew hundreds of signatories. He objected that politicians were dipping into the collections of the Louvre and France’s other national museums with no other aim than money, and that there was no real curatorial or artistic programme underpinning the exercise.

Nearly a decade later, he continues to express qualms about Abu Dhabi. He maintains that works of art are being rented out to the Gulf emirate, even though no one is brave enough to use that term. He worries that a set of extremely fragile paintings and sculptures is being sent into a region of the world where geopolitical instability and the risk of conflict are even higher than they were when the accord was signed. He is critical of the Pompidou Centre, too, for shipping its art abroad. “There is something absurd about this obsession with circulating works,” he says.

Still, with budgetary belt-tightening very much the order of the day, the future will probably see more, not less, museum replication. French art historians, critics and curators will doubtless continue to warn that masterpieces must be handled with care and displayed only where there is a valid scholarly purpose.

Yet French museums will be increasingly compelled to turn to outside sources for financing and to lend their brand, their know-how and collections to parts of the world where masterpieces of Western culture are all but inaccessible. In a century or so, Louvre Abu Dhabi and Pompidou Malaga will doubtless be singled out as the first of many French museum outposts.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi