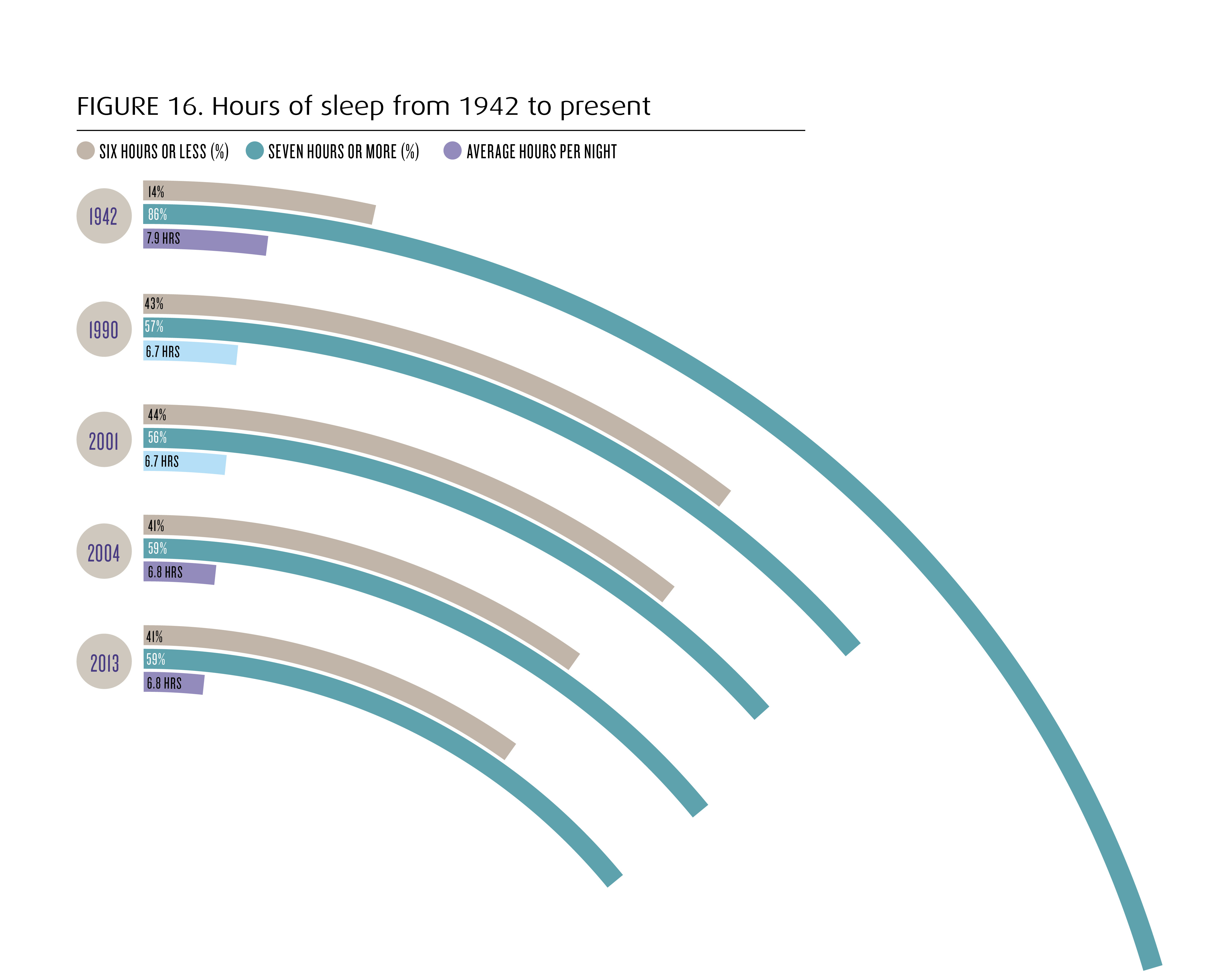

The old cliché that you need eight hours of sleep a night has proved hard to shake over the past century even though it has been consistently challenged. Even as far back as Napoleon – who famously said “six hours for a man, seven for a woman and eight for a fool” – the notion that the human body was designed to rest for a third of the day has been contentious.

The emergence of the smartphone, tablet and e-reader has added further weight to the argument as more and more people have ignored the warnings that those devices are fundamentally changing their sleep patterns. The blue light of the TV was once deemed to be disruptive to our sleep as more people installed sets at the foot of the bed but that now seems quaint with smartphones and tablets, held inches from the face, the new scourge of the insomniac.

Yet there is nothing new about technology causing havoc with how we sleep. The invention of first the candle and then powerful street lighting fundamentally changed the pattern of human behaviour. Prior to the 17th century, humans were prone to two bouts of sleep. One initial period immediately after a day’s labour and then another that followed a brief waking period of two hours when people would visit neighbours, copulate, visit the bath house or engage in prayer.

There is nothing new about technology causing havoc with how we sleep – the invention of first the candle and then powerful street lighting fundamentally changed the pattern of human behaviour

The emergence of the candle did not initially change much as few people would want or need to venture into the night where the streets were teeming with criminals and drunkards. It was with the advent of strong street lighting via lamps that evenings became fashionable and thought of lying around in bed all night was seen as a waste. That ushered in a period of the ‘eight hour sleep’ as segmented sleeping disappeared. That did however coincide with the rise of insomnia as a medical condition which academics and circadian specialists attribute to the body’s inability to adapt to one long slumber spell.

The impact of technology

Nonetheless that pattern has persisted as lights have pervaded all facets of life. Tempur’s survey has found that the majority of people go to sleep between 10pm and 11pm and slightly less than half wake-up between 6am and 7am. A lengthy one-off sleep is near universal.

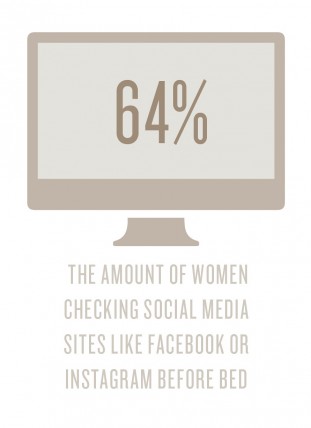

Yet what has changed is the preponderance of those gadgets. While the survey shows that nearly three quarters of men check e-mails before trying to get to sleep while nearly half of woman do the same. The roles are reversed in terms of checking Facebook, Instagram or Twitter with 64 per cent of women doing so compared to compared to 53 per cent of men.

Those devices are having as significant an impact as the street lights did in the 17th century however with the dreaded ‘blue light’ disrupting sleeping patterns. “Everyone says they won’t use their phones before they go to sleep but come on, we know it’s bad for us but we still do it,” said CCS Insight analysts George Jijiashvili who specialises in sleep gadgets.

Those devices are having as significant an impact as the street lights did in the 17th century however with the dreaded ‘blue light’ disrupting sleeping patterns. “Everyone says they won’t use their phones before they go to sleep but come on, we know it’s bad for us but we still do it,” said CCS Insight analysts George Jijiashvili who specialises in sleep gadgets.

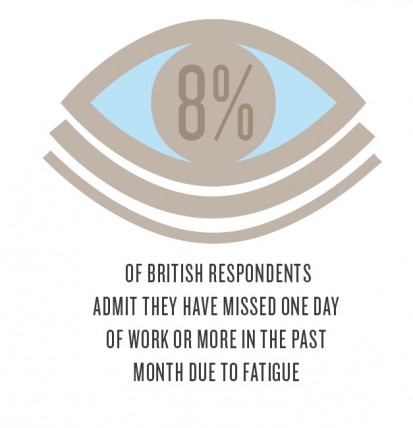

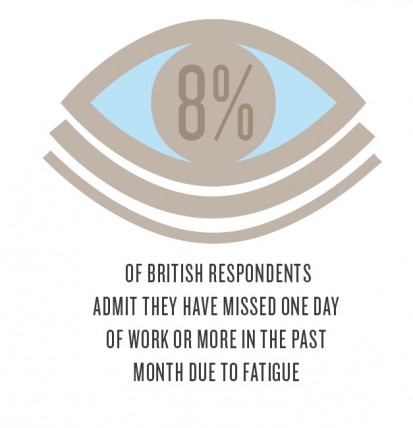

Britain is known to be technology obsessed so no wonder then that the Tempur survey shows the British are struggling to get enough sleep. They were the only country to score on the ‘often’ tired at work mark with bad sleep causing 8 per cent of British respondents to admit they have missed 1 day of work or more in the past month due to tiredness.

Perhaps naps when the smartphone has run out of battery are the answer with only 5 per cent of British people taking short sleeps compared to 16 per cent in Japan.

[embed_related]

Collating data for a better sleep cycle

Yet the saviour is more likely to be the technology itself. Mr Jijiashvili pointed to software called f.lux which cuts the ‘blue light’ out of laptops, smartphones and tablets and replaces it with amber colour. Screens are designed to look like the sun but that also fools the brain into thinking it should be awake. The amber colour helps to combat that natural instinct and helps when dozing off.

That may help us to get to sleep but it won’t change our sleeping patterns. What is happening is that hundreds of companies are now using sensors to collate information on how we sleep –everything from heart rates to moisture on our skin to how long we stay in deep sleep as opposed to REM.

Yet for all the investment in sleep technology, nothing has yet moved the dial for the better. “At the moment you go to bed, you wake up and check the app to find it telling you that you’ve slept terribly. It’s not really helping,” said Mr Jijiashvili.

Yet for all the investment in sleep technology, nothing has yet moved the dial for the better. “At the moment you go to bed, you wake up and check the app to find it telling you that you’ve slept terribly. It’s not really helping,” said Mr Jijiashvili.

That data could one day be invaluable in designing a better sleep cycle. We can set wristbands to nudge us to go to bed at an optimal time or set alarms to analyse the data to select the best time to wake up in terms of sleep cycles. The smart home usually focuses on energy use and entertainment systems but can also have a revolutionary impact in the bedroom by adjusting lighting to wake us up naturally and the sounds we hear when we do.

Small companies such as Kokoon are raising money on crowdfunding platforms to design products to improve our subconscious lives by adding aural stimulus to help us sleep and wake up.

The future of sleep may not be a return to the bi-modal days or yore, nor the eight-hour dream. It may instead be one where slumber can be designed, improved and controlled.

The impact of technology