The internet of things (IoT) has been hailed as ushering in a technological revolution that will transform our lives for the better. With every conceivable tool and device we use seamlessly interconnected through the cloud, everything we do from work to leisure will be increasingly automated, efficient and easily configurable in ways that were previously unimaginable. But even before the IoT revolution has fully arrived, associated costs are rising exponentially. A new Accenture report estimates that businesses could incur up to $5.2 trillion over the next five years in additional costs and lost revenue due to cybercrime “as dependency on complex internet-enabled business models outpaces the ability to introduce adequate safeguards that protect critical assets”.

According to the report, some 80 per cent of business leaders admit having a hard time ensuring their companies are protected. And it’s not just businesses. Government figures reveal that UK residents are more likely to be a victim of cybercrime or fraud than any other offence.

Even rudimentary cybercrime pays huge dividends

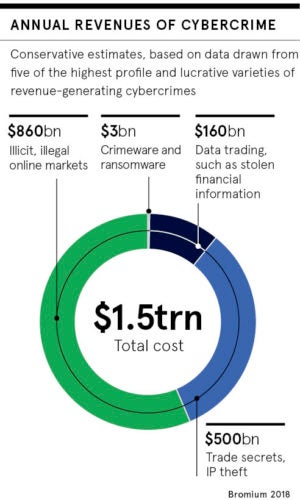

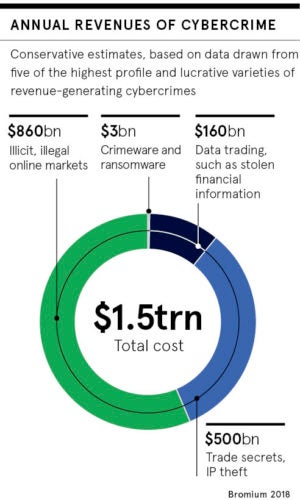

While the costs to legitimate businesses and consumers escalate, so do profits for cybercriminals. A 2018 University of Surrey study conservatively estimates that cybercrime carried out on well-known platforms such as Amazon, Facebook and Instagram rakes in a cool $1.5 trillion, equivalent to the GDP of Russia.

This is not even particularly sophisticated cybercrime. According to study author criminologist Dr Michael McGuire, these platforms are being used to evade tax, move money, trade illicit drugs and sell fake goods. As technology advances, the opportunities for such crime will transform.

“In a world where almost every instruction, process, transaction and secret is located in cyberspace, there could be a wealth of opportunities for criminals,” warns an October 2018 report from the UK Ministry of Defence Global Strategic Trends programme. With relatively low startup costs and potentially huge profits, organised cybercrime has an obvious business appeal, the report says, especially for “people in countries with limited economic opportunities”.

Cybercriminals rapidly innovating to improve their productivity

Most cyberattacks in the European Union, for instance, actually come from outside the region.

Most cyberattacks in the European Union, for instance, actually come from outside the region.

And like any other business, cybercriminals are rapidly investing in innovations and new techniques to improve their productivity. A report by the Tel Aviv-based global IT security firm Check Point Software Technologies highlights how cybercrime methods have become “democratised” and available to anyone willing to pay for them.

“Cybercriminals are successfully exploring stealthy new approaches and business models, such as malware affiliate programs, to maximise their illegal revenues while reducing their risk of detection,” says Peter Alexander at Check Point.

Maya Horowitz, Check Point’s director of threat intelligence and research, paints a picture of an increasingly corporatised approach to cybercrime. Attacks involve organised teams of programmers, corporate insiders, IT technicians and phishing experts. These teams even issue job ads for new roles for the next hack.

How the dark web is facilitating organised cybercrime

This sort of activity has been facilitated by the dark web, a hidden part of the internet where criminals can act undetected, using complex encryption and anonymisation tools. The dark web first hit the headlines in 2013 when the FBI shut down the notorious Silk Road website, which ran on online black market in illicit drugs. The dark web thrives as a treasure trove of automated software applications which can be used to troll and attack vulnerable accounts automatically.

“A cybercriminal can simply purchase any number of password-cracking programs and can rent or purchase exploit kits which contain many attack tools,” says Corey Milligan, one of the US Army’s first cyber operations technicians and now a senior threat intelligence analyst at Armor Defense, a cloud security firm in Texas. “The kits are designed to make it quite trivial for an average computer user to successfully attack various vulnerabilities and then distribute malware or potentially wipe a victim’s hard drive.”

Cybercrime in the dark web is thriving, especially as people can be hired through third parties to conduct attacks. “The greatest impact they can have is when they are hired to do something for somebody else,” adds Mr Milligan.

In effect, a whole new underground industry has emerged, dubbed “malware as a service”. And as the IoT expands, so too will opportunities for commercial and criminal growth.

According to Intel, we are moving from a world of two billion smart, wirelessly connected objects in 2006, to a world of 200 billion by 2020. By 2021, half a billion of these will be wearable devices.

Dr Janusz Bryzek, a Silicon Valley guru who pioneered sensor technology, predicts that within 20 years there will be 45 trillion networked sensors, devices which detect and respond to physical environmental changes such as light, heat, sound, moisture and pressure.

Connected devices are top targets for cybercrime

Already, attacks on connected devices, including routers, cameras, thermostats, electronic appliances and alarm clocks, are among the top cybercrime targets. But companies are not doing enough to protect these devices, preferring to get them on the market without delay.

“The risk is global. Regardless of the size of your business, or what sector you’re in, if you’re connected to the internet, you’re at risk, as anyone can find you and any of the assets you have connected,” says Mr Milligan.

Most businesses remain dramatically behind the curve on safeguarding against these heightened risks. In 2018, the Ipsos MORI Cyber Security Breaches Survey found that four in ten businesses and a fifth of charities had experienced a cyberattack. The findings led King’s College London’s Cyber Security Research Group this January to call on the UK government to name and shame companies whose cybersecurity measures fail to protect the data of consumers.

Complacency is not an option. In a taste of things to come, one of the largest electric power companies in America, Duke Energy, was hit with a $10-million regulatory fine in early-February for 130 violations of physical and cybersecurity standards. If companies fail to act now, governments will have little choice but to make them pay later.

Even rudimentary cybercrime pays huge dividends

Cybercriminals rapidly innovating to improve their productivity