If we are to keep our democracy, there must be one commandment: thou shalt not ration justice.

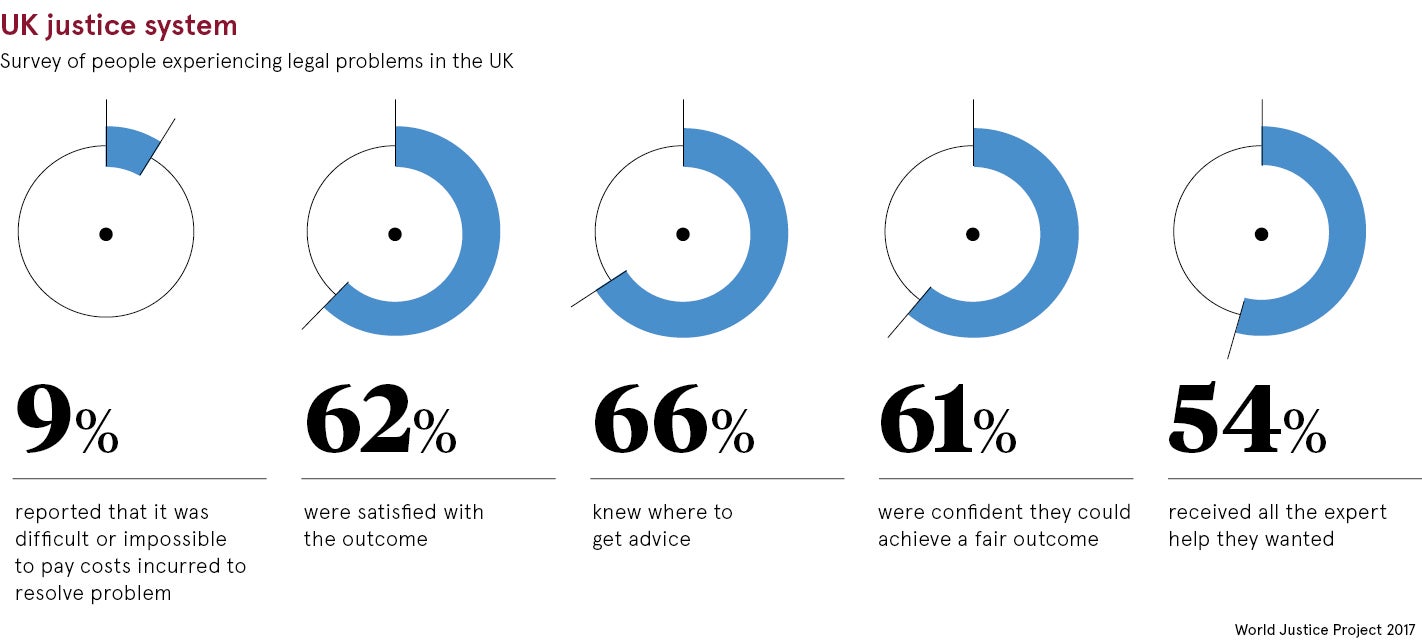

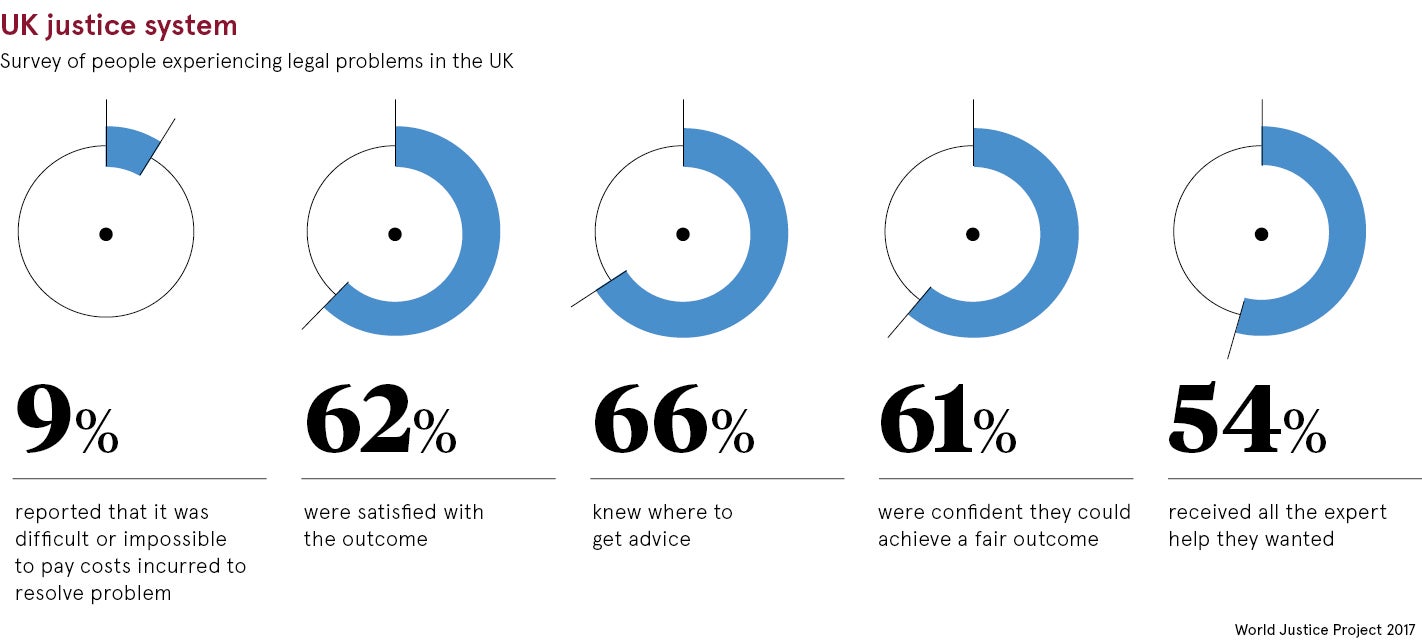

Yet some 2,500 years after Sophocles made his proclamation on legal equality, access to justice is still one of the most frequently raised concerns directed to the European Parliament, while on average only 54 per cent of people worldwide feel confident of a fair outcome to a legal problem.

A core part of access to justice is public access to the law itself, but it is also important that lawyers can access the law efficiently

Technology could play a pivotal role in changing that as jurisdictions across the globe are grappling with improving digital access to theoretically public court judgments, while chatbots provide signposting for everyday legal issues and civil tribunals are becoming available online.

Tech is already granting more access to public legal information

“The principle that tech can play a large role in getting access to justice to more people is clear,” says Lord Peter Goldsmith, chair of the Access to Justice Foundation.

Easy, free access to public legal information is a key concern for Daniel Hoadley, research and development manager at the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting.

“A significant number of [public] judgments are only accessible to paying subscribers, effectively creating a scenario where comprehensive access to the decisions of judges depends on the ability to pay for it,” he points out.

In the United States, a Harvard team has been tackling the problem and last month launched its Caselaw Access Project in partnership with Ravel Law, the culmination of five years of work to digitise 40 million pages of court decisions.

Adam Ziegler, director of the project, aims to encourage individual state jurisdictions to move to digital-first publishing of case law and believes it “can definitely be replicated”.

“It is expensive, but given the impact, it should not be prohibitive,” he says.

“A core part of access to justice is public access to the law itself, but it is also important that lawyers can access the law efficiently, so price does not become a barrier to lawyers serving the underprivileged and under-resourced in society.”

Europe and Canada leading the way in public access to justice

In the European Union, the Eur-Lex legal data platform’s freely available statutes and case law from EU institutions are now available in a mobile-friendly format, after revisions to the service in September.

Meanwhile, the £1-billion digital reform process being undertaken by the UK’s HM Courts and Tribunals Service will be in the spotlight alongside other international programmes during the inaugural International Forum on Online Courts next week, discussing the technological advances being made in justice systems globally.

“While tech is exciting, it’s important to map and redesign the system properly,” says Alex Smith, innovation manager at global law firm Reed Smith. “The people and process driving the justice system are probably more important in such sensitive areas as any technology.”

Online courts are already a reality in Canada, where the province of British Columbia launched its Civil Resolution Tribunal (CRT) service in 2016 and has dealt with more than 8,000 disputes to date.

Currently dealing with small claims and strata property, or apartment buildings, the CRT’s success is leading to its expansion and from April 2019 the tribunal will also tackle motor vehicle accident claims.

There are drawbacks to using technology to provide legal information

There are pros and cons, says Lord Goldsmith: “There is a risk that as tech is used more in wider delivery of justice, there will be an increased justice gap for people who don’t have that access or tech literacy.”

A combination of technology and face-to-face help is a model supported by Lucy Scott-Moncrieff, adviser to the International Bar Association’s Access to Justice and Legal Aid Committee.

Currently working on the pilot Jeanie Project, a triumvirate of civil society volunteers, a tech platform and pro bono lawyers, she believes information must be backed by specialist knowledge.

“Legal tech that gives people unjustified confidence is hardly helpful,” says Ms Scott-Moncrieff. “Knowledge is power, but pure information isn’t necessarily knowledge.”

As mobile use expands, the role of the legal chatbot, such as DoNotPay, is gaining ground, though access to justice expert Roger Smith questions the “hype” around the current “quite mechanical” processes.

How a chatbot is working to democratise law

This year saw the launch of the Global Legal Hackathon, with entrants competing to share their innovative tech projects.

Among winners was the Hong Kong-based Decoding Law project, a machine-learning browser plugin that has already gained the attention of the region’s Department of Justice.

The chatbot-style programme aims to democratise law, say its creators, and help people, especially unrepresented litigants, by breaking down complex legislative drafting into simple language.

Mr Smith believes the chatbot model has the potential to grow in sophistication, using more advanced artificial intelligence and facial recognition to deliver a more tailored service.

Lord Goldsmith concludes: “We have to look carefully and intelligently, so tech meets the need, but doesn’t exacerbate problems for those who are the most in need of these services.”

Tech is already granting more access to public legal information

Europe and Canada leading the way in public access to justice