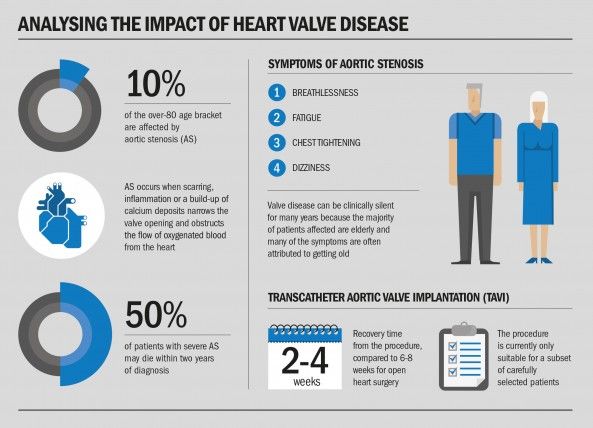

The most common and life-threatening heart valve disease is aortic stenosis (AS), which affects up to 10 per cent of the over-80 age bracket, while many more have other silent valve diseases.

Diagnosis is often only made at an advanced stage because its classic symptoms of breathlessness, fatigue, chest tightening and dizziness can be misinterpreted as a natural part of ageing.

AS occurs when scarring, inflammation or a build-up of calcium deposits narrows the valve opening and obstructs the flow of oxygenated blood from the heart.

Muscles in the heart-chamber wall are forced to stretch and thicken to push blood through the valve leading to an increased likelihood of heart failure, and up to 50 per cent of AS patients may die within two years of diagnosis.

It cannot be treated with medicines, but aortic valve replacement can save lives, and promote a longer and better quality of life.

This can be achieved by open heart surgery or transcatheter aortic valve implantation, known as TAVI, which enables valve replacement without opening the chest. The new valve is squeezed down into a balloon and positioned for implantation, via a catheter introduced through the femoral artery, or other keyhole techniques are used.

The procedure, currently suitable for carefully selected patients, is shorter than open heart surgery, involves less pain and recovery time is enhanced from six to eight weeks to two to four weeks.

But the key to treating AS is early diagnosis and getting the patient on a swift pathway of treatment.

“Surgical treatment of AS by means of open heart or keyhole valve surgery restores life expectancy back to that of the normal population, so timely intervention not only saves lives, but also improves quality of life over many years,” says Bernard Prendergast, consultant cardiologist and cardiology clinical director, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. “It is a major winner if the patient can get access to it before it’s too late.”

One million lives are at risk because of poor knowledge about the dangers from heart valve disease

He advocates greater public and GP awareness of the symptoms to boost the diagnosis rate, and allow patients the opportunity to access the correct surgery.

“Valve disease is almost always clinically silent for many years,” he says. “It may be insidious for a long time and, because the majority of patients affected are elderly, many of the symptoms are often attributed to getting old. The cardinal symptoms of AS are shortness of breath, chest pains due to angina and dizziness or blackouts.

“But they don’t develop until very late in the condition and might not be noticed without the use of a stethoscope to detect a heart murmur.

“Clinical suspicion needs to be raised. If elderly patients come with the symptoms of AS, a doctor needs to think about the condition as a possible diagnosis. The symptoms should not be brushed off as the effects of ageing or as lung disease, as you can easily waste six months sending the patient down the wrong pathway.”

Dr Prendergast believes that GPs have a difficult task assessing elderly patients, who may present with several conditions, in a tight ten-minute consultation time frame.

“As well as improved levels of awareness in primary care, the public too needs to have more awareness of the symptoms of heart valve disease,” he adds. “If GPs see a patient with these symptoms, they should suspect the diagnosis and listen to the heart. We then need to offer timely access to echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis and more specialists in valve disease, who know how to handle the information and offer the best treatments to patients.”

The recently formed physician-patient group Heart Valve Voice estimates that one million lives are at risk because of poor knowledge about the dangers from heart valve disease.

“It can have catastrophic consequences if the symptoms are mistaken or simply put down to being a sign of ageing. At the moment many people are referred to surgery too late and, as a result, they do not derive the optimal benefits from surgery and their future health may be compromised,” says Professor Ben Bridgewater, chairman of Heart Valve Voice and consultant cardiac surgeon, University Hospital of South Manchester. “It is important that we push for earlier diagnosis and treatment.”

Ivy Lovell, from Orpington, Kent, had no idea she had valve disease and it was not diagnosed even though she had suffered two falls from dizzy spells. She was eventually treated at King’s Hospital in London with a TAVI and says: “I’ve felt in perfect health. I’m 90 years of age and I can take long walks and drive to see my family. Effective diagnosis and management gave me my life back.”

For more infomation please visit

www.bhf.org.uk or alternatively the British Heart Valve Society

www.bhvs.org.uk