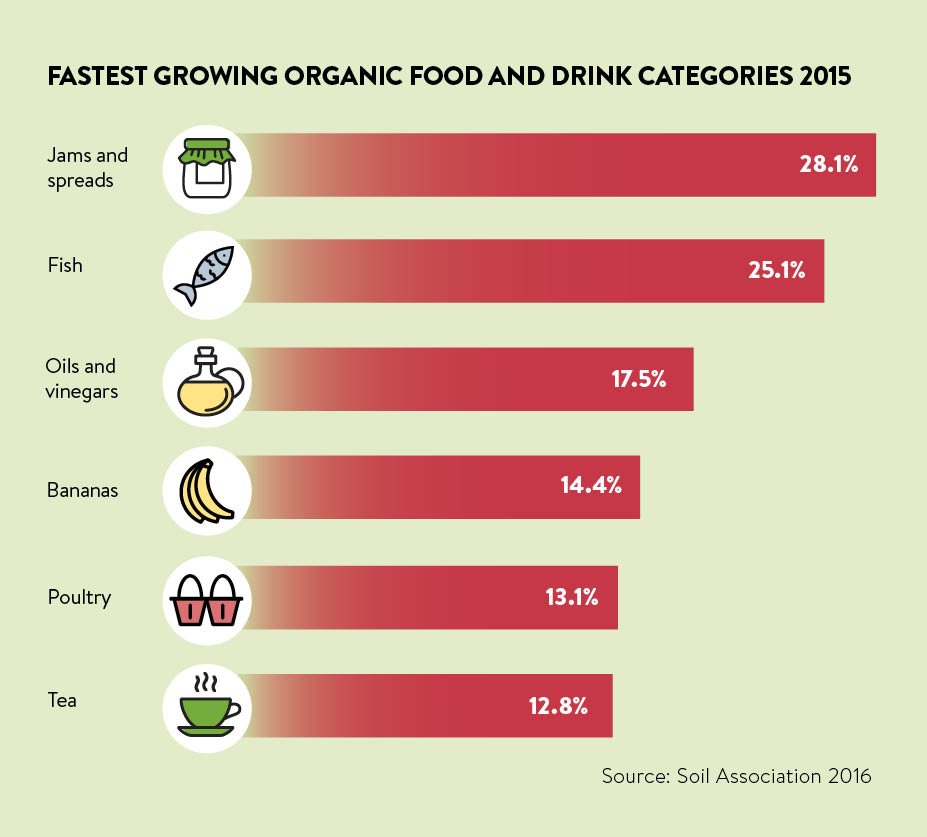

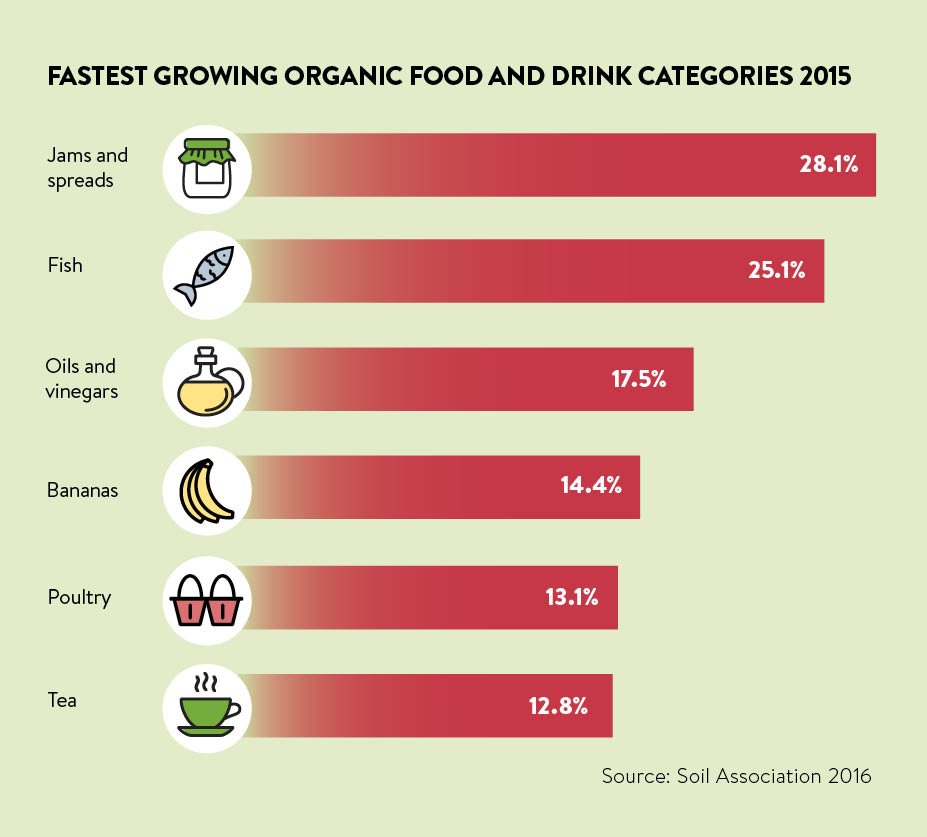

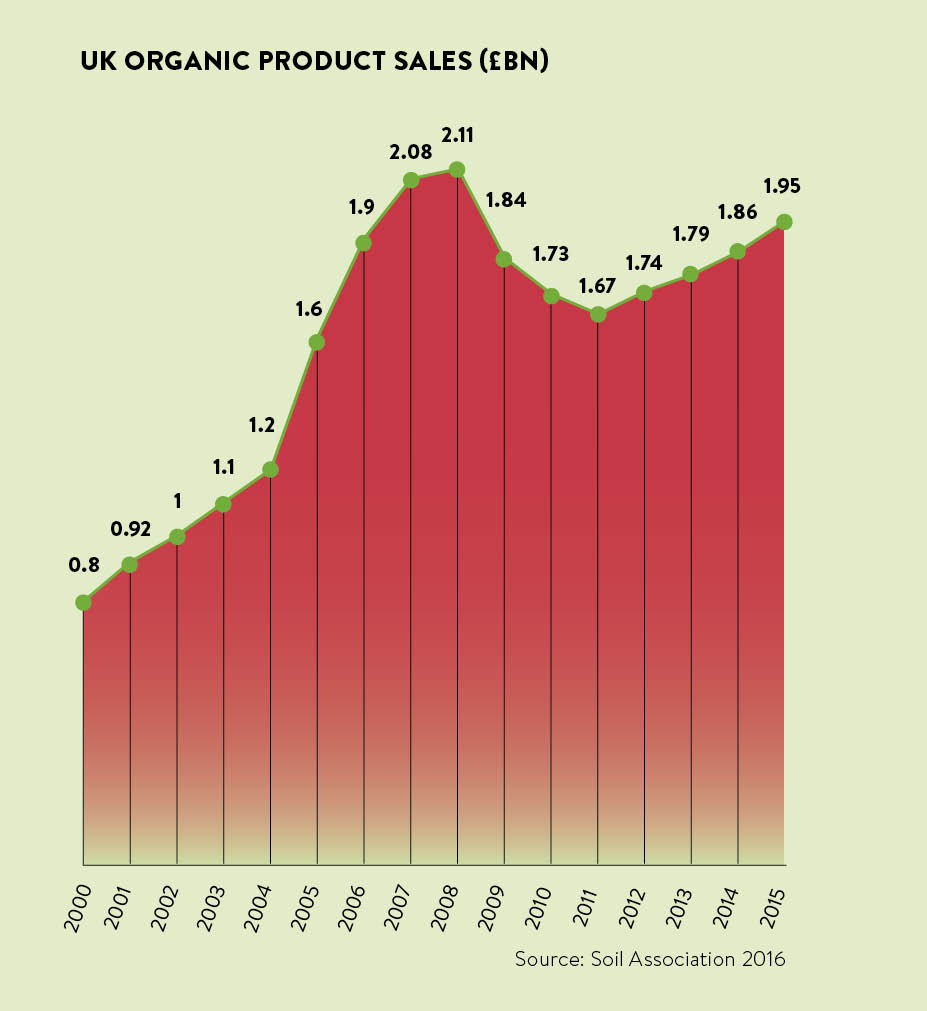

The organic sector in the UK is on a bit of a roll. While sales of non-organic food and drinks fell by 1 per cent last year the organic market grew at 4.9 per cent. But it was not always so. When the financial crisis hit in 2008, sales of organic goods plunged.

“The wheels came off and the market declined because of the recession,” says Paul Moore, chairman of the Organic Trade Board. The UK was the only market where this happened; in other strong organic markets, such as the United States, Germany and France, growth slowed but sales did not fall.

For the full infographic click here

Trends

In continental European markets with similar GDP per capita, spending on organic produce is about twice that of the UK, in part because government support for organic goods is much stronger.

The UK is the world’s fourth-biggest organic market after the US, which accounts for a massive 44 per cent of the $50-billion organic market, Germany takes 14 per cent and France 9 to 11 per cent.

I don’t think the consumers went away, it was more that the products were not available so people had to seek them out elsewhere

The sector is also growing fast in markets such as China, Japan, India and the Middle East. The UK makes up about 4 per cent of global organic sales, with organic food sales valued at about £1.9 billion in 2015, and natural and organic personal care products, including beauty, valued at about £225 million.

The reason for the UK organic sector’s woes, earlier in the decade, was that the vast majority of organic food – some 80 per cent – was sold through the large supermarket chains and, when austerity bit, they changed their focus to price and value brands.

Now the share of the large retailers is down to 67 per cent and customers are looking elsewhere such as organic box schemes and online. “I don’t think the consumers went away, it was more that the products were not available so people had to seek them out elsewhere,” says Roger Kerr, chief executive of Organic Farmers & Growers, a certification organisation.

As a result, while sales of organic in supermarkets grew by 3.2 per cent last year, this rise was far outpaced by the 7.5 per cent increase for independent retailers, and the 9.1 per cent growth in box schemes and online sales.

And as more meals are being eaten outside the home, organic sales to the catering sector have grown by 15.2 per cent. Non-food sales have grown even faster – textiles by 16 per cent and health and beauty by 21.6 per cent, according to the Soil Association – although these sectors are dwarfed by the organic food market.

Organic still makes up only a small part of the overall market, but it is much stronger in certain sectors. UK baby food sales are 59 per cent organic, while the market share for carrots is 14 per cent and for yoghurt 8.3 per cent. Total sales of organic products are set to exceed £2 billion this year.

[embed_related]

Could demand exceed supply?

The prospects for the sector are bright, with sales growth of around 5 per cent predicted for 2016. One reason for confidence is the profile of those who are buying organic goods. While there was an assumption that buyers were older, with more disposable income and families that have left home, “there has been a shift to a younger group”, says Mr Moore.

“This is being driven by the millennial generation. They are very engaged with food. They want to know where their food comes from, how it is farmed and how production staff are treated. It’s much more than just something they put on the plate,” he adds. This is in part driven by the 2013 scandal over horsemeat and partly the increased focus on provenance, transparency and accountability that the social media revolution has brought about.

This suggests that the organic sector will be more resilient should the economy face another downturn, perhaps prompted by the UK’s decision to leave the European Union.

Indeed, one of the main worries for the sector is being able to meet increased demand. “We are fast reaching the point where demand for organic food could exceed supply, leading to increased imports,” says Liz Bowles, head of farming at the Soil Association. “For the last three years, organic food sales have been rising steadily, but the amount of land under organic production has not risen in line with the increase in demand.”

One reason for this failure to increase supply is farmers’ concern about their ability to manage their farms under the constraints of organic rules, particularly arable farmers, who have to manage without chemical fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides.

There is also a funding gap during the conversion period, when production is reduced. The government offers support payments to help people to convert from conventional to organic farming, but these are the lowest in Europe and their future is uncertain as the entire farming support regime is up on the air following Brexit. “No UK government has ever really shown much enthusiasm for organic,” Mr Moore claims.

Farmers, organic and conventional, receive much support from the EU in terms of the Common Agricultural Policy, the consultancy Organic Monitor says. “UK farmers receive about £2.5 billion to £3 billion in subsidies from the EU. Farmers also get grants to encourage them to convert to organic farming practices. The organic farming sector is expected to be adversely affected if conversion grants halt and if there is less financial support for farmers.”

The organic food sector would become more dependent on imports, mainly from European countries, but because of the fall in the value of the pound, these would be more expensive.

Despite the challenges, the sector is confident that organic is well placed to thrive in the years to come. “There is a broader trend of interest in provenance and health. People are looking for natural alternatives,” says Patrick Cairns, chief executive of Wessanen, a producer of organic snacks. “Organic is the best certification that a product has been produced well – and we are helped by the wired world we live in.”

There will be a continued acceleration in the growth of the market, says Mr Moore. He concludes: “We know consumers believe organic food is healthier, tastes better and, more importantly, is worth it. Organic has earned its place in the retail scene – customers want to see retailers doing the right thing and organic is part of that.”

CASE STUDY: BABY FOOD

Baby food is one of the real successes of the organic sector, indeed it dominates the market with more than half of all baby food certified organic – 59 per cent, according to the Soil Association – in a category that barely existed before the 1990s.

One reason for the success is the leading brands in the field, such as Organix, Ella’s Kitchen and HiPP, have a very clear position, says Anna Rosier, managing director at Organix. “We are organic and that’s it. It’s a very clear message to parents, who don’t want to feed their children anything they are uncomfortable with.”

Another advantage baby food has is that it is manufactured, so some of the extra cost of using organic produce is diluted through the supply chain.

The success of baby food has spilled over into non-food goods as well. Sales of organic baby clothes are booming, says the Soil Association’s Organic Market Report. “New parents have a strong tendency to opt for organic for their babies and toddlers,” the report says. “This is true for sales of food, beauty and, increasingly, in textiles. Parents feel that organic cotton that hasn’t been subjected to as many harsh chemicals and pesticides is a better choice for their little ones.”

However, while being organic is a good basis on which to build a business, it is not enough on its own, says Ms Rosier. “The organic companies have been very innovative with regard to issues like taste, variety and packaging. Some of the non-organic baby food companies have been more conventional in their approach,” she says.

Trends