Decarbonising commercial real estate by 2050

All new buildings must be net-zero carbon in operation and embodied carbon reduced by at least 40% by 2050 – how can this be achieved?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has set the target for Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions to plateau no later than 2025, halve by 2030, and reach net-zero by 2050. The built environment is a significant contributor, responsible for 39% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The World Green Building Council has therefore issued a challenge: by 2030, all new buildings must be net-zero carbon in operation and embodied carbon reduced by at least 40%, while all buildings must be net-zero by 2050.

For the commercial real estate (CRE) sector in particular, this is a difficult proposition. Simply replacing everything with brand new high-spec buildings is not feasible, either economically or environmentally. According to UKGBC, approximately 70% of the UK’s non-residential building stock was constructed before the year 2000. Put another way, more than 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 already exist today. As a result, much of the sector will have to retrofit.

To give just one example, according to David Bownass, head of UK Net Zero Design Consulting, JLL, “the pace of office redevelopment needs to at least double from levels seen over the last ten years”.

According to figures from UCL, the five largest UK CRE sub-sectors in terms of energy consumption are offices (27,620 GWh, 17 per cent), retail (27,340 GWh, 17%), industrial (25,740 GWh, 16%), hospitality (16,980 GWh, 11%) and health (17,380 GWh, 11%).

Energy benchmarking

To drive those numbers down, the BEIS and property industry groups are building on existing legislation such as Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) and Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES). Energy benchmarking for operational use “is extremely likely to come into force,” say UCL, “first for offices and then for other sectors.” At present buildings in the F and G rating category cannot be let and must be improved. UCL believe it likely that this will be lifted for D and E grades, but admit that this measure alone won’t get these buildings to net zero. The Government’s 2021 ‘Building Back Greener’ strategy sets a minimum energy efficiency standard of EPC band B by 2030 –better, but still not good enough.

“Real estate is fundamentally about creating better places for people, but we cannot thrive without a thriving planet”, argues Joey Aoun, net zero implementation lead at Savills Investment Management. “Adopting sustainable construction materials, circular approaches and efficient practices such as dismantling, adaptability, prefabrication and modularity [are needed] to minimise the embodied carbon emissions in the built environment.”

The pain points of doing so, however, include “works that are costly, and often require vacant possession, which again only adds to the financial cost”, says Chiara Essig, head of strategic sustainability services, EMEA, at JLL. But she adds that combining decarbonisation measures with existing capital improvements and refurbishment plans will reduce the marginal cost. Brett Ormrod, net zero carbon lead for Europe, LaSalle Investment Management, agrees that such “pain points contribute to delays on action towards decarbonisation”, including rising interest rates.

However, while action might be expensive, inaction is far costlier. Emily Hamilton, head of ESG at Savills Investment Management, points out that while $100 trillion is the estimated investment required to reach net zero by 2050, it compares to a $178 trillion cost of inaction: “It doesn’t take a maths genius to see the business case for scaling investment now… the initial investment required for energy-efficient retrofits can be recouped through a combination of energy savings and rental premium within a relatively short timeframe.”

Indeed, JLL’s 2022 Future of Work Survey found that 74% of organisations said they would be willing to pay a premium for leasing a building with leading sustainability or green credentials, and 22% said they already have. CBRE found a 21% rent premium for certified office buildings compared to non-certified assets over a five-year period. In Copenhagen, Barcelona and Amsterdam, the premium was as high as 29%, 27% and 26%, respectively.

Regulation

There are regulatory winds blowing, too. The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) has proposed European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). At the same time, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is moving to deliver global sustainability-related disclosure standards, while the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is proposing similar rules that would impact the CRE sector.

Deloitte comments that this is leading firms such as Brookfield and JP Morgan Chase to “help manage energy usage and carbon in the properties they occupy in anticipation of potentially increased disclosure requirements and to meeting ESG and sustainability goals.”

As the Deloitte survey notes, however, “it can be unclear whether this includes only landlord-controlled emissions or those controlled by both tenant and landlord.” The tenant-owner relationship is crucial to decarbonising the CRE sector, says Ormrod: “We must take steps to turn what has historically been a transactional relationship between tenants and owners into a collaborative partnership.”

The NABERS UK standard, which provides an efficiency performance rating from one to six for offices, recommends an energy split between “base building” and “tenant spaces”. The UCL report also highlights ‘green leases’ or ‘performance-based leases,’ which enable landlords and tenants to meet environmental targets cooperatively by sharing energy data and upgrade costs. As Essig comments, “landlords’ and occupiers’ sustainability objectives are usually well-aligned, so it’s just about getting the right people in the room.”

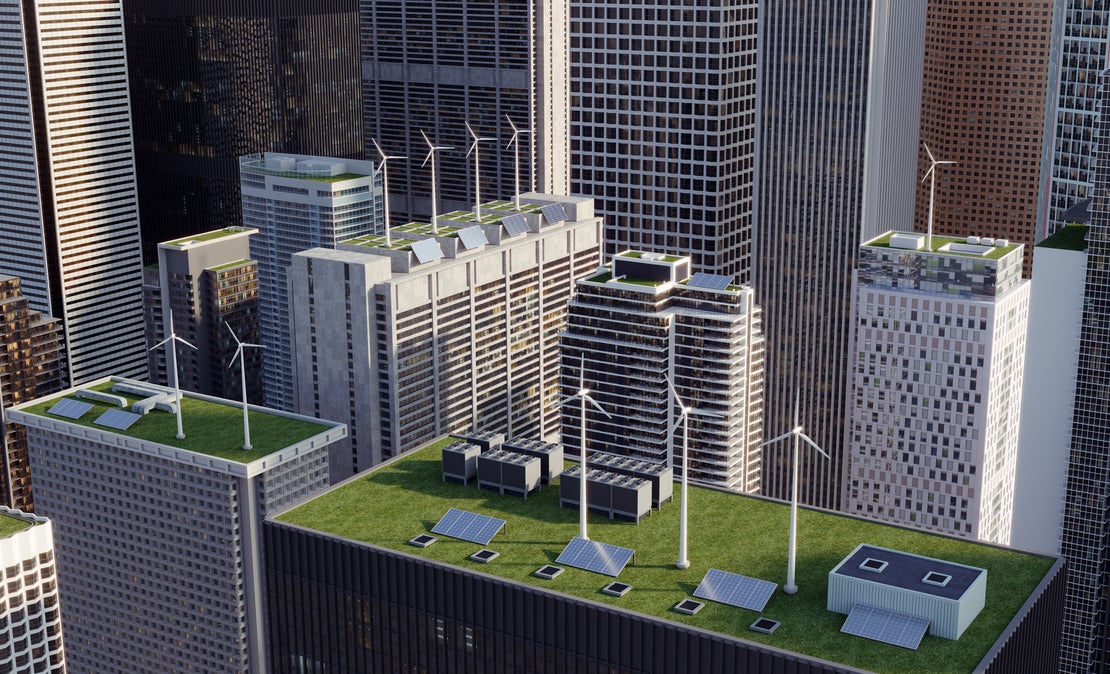

The ultimate goal is worth keeping top-of-mind, too: what a zero-carbon built environment will look like in 2050. For Aoun, it will be “a sustainable and resilient future. Buildings will be energy efficient, powered by renewable sources, and constructed with low-carbon materials and efficient techniques”. Similarly, says Ormrod, “we can hope to have re-imagined our buildings’ relationships with nature, realising a true balance between the natural environment and technology both operationally and physically.” It is a future worth building for.

The technology powering commercial real estate’s net-zero strategies

Every building can be decarbonised by gathering and analysing the data needed to improve their design, retrofit and operation

Against a backdrop of recent climate disasters, from Brooklyn to Libya, the need to decarbonise the commercial real estate (CRE) sector is increasingly hard to ignore. Buildings are a major contributor to climate change, responsible for 23% of all UK carbon emissions, 30% of which come from non-domestic buildings. Yet, writes Professor Paul Ruyssevelt of University College London, “Despite the importance of the sector and the significance of its emissions, it has been little researched by comparison to the domestic building sector in the UK. What we do know is that little progress has been made in decarbonising.”

The overarching goal is clear: achieve net zero carbon by 2050, as stipulated by the Paris Agreement and written into UK law. However, it’s easy to view 2050 as a distant horizon. “If we don’t act to decarbonise our buildings now, we won’t achieve our climate goals,” warns Ben Pettitt, sector lead for Real Estate UK & Europe, at IES, the global climate tech company. A key target year, he says, is 2030, when emissions need to be reduced by at least 43% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels to keep the climate within the 1.5°C limit. “That’s around six years away“, says Pettitt. “We need continuous year-on-year emissions reductions from now on.”

The CRE sector has a long way to go on its decarbonisation journey, so it’s good to start with the low-hanging fruit and quick-wins. IES believes that every building can be decarbonised by gathering and analysing the data needed to improve design, retrofit and operation. “You need to understand where you are right now, and data is central to that,” says Pettitt. “When looking at the efficiency of buildings, how buildings are performing and the potential for buildings to decarbonise – data can give us the answers. But we need to consider the quality of that data and where it comes from.”

The power of digital twinning

As the UCL research finds, many organisations possess only rudimentary data on their buildings, sometimes merely utility bills, which barely scratch the surface of a building’s environmental performance. This is where IES plays an integral role: by capturing, analysing and simulating data from a range of sources, it provides a foundational basis upon which informed decarbonisation strategies can be based.

Utilising IES’s industry-leading technology allows organisations to “digitise their buildings” – creating ‘digital twins’, or highly accurate digital replicas of buildings – to virtually test which measures will have the most profound impact. Pettitt explains that their technology uses a powerful physics-based simulation engine alongside the data to accurately predict “the carbon reduction and energy savings associated with hypothetical changes” and inform net zero investment and operational strategies.

Once you have the data, understanding how to act upon it is the next piece of the puzzle. Pettitt asserts that the first step in the energy hierarchy is “to reduce, and that’s about driving operational efficiency and reducing consumption as far as you can”.

However, energy reductions need to be carefully balanced against occupant needs. To navigate this, IES’ technology offers the ability to optimise operational energy efficiency of buildings whilst maintaining and enhancing the comfort, health and wellbeing of occupants through managing lighting, air quality and thermal comfort levels.

Data-based strategy

When it comes to the next stage of investing in building upgrades, heat pumps in many cases will be key to decarbonising the built environment, but currently their effectiveness is compromised “if the building fabric is really inefficient.” Therefore the underlying efficiency of the building, in terms of “its thermal performance” and “airtightness,” must first be thoroughly evaluated and optimised. Only then should subsequent steps be taken to install low-carbon technologies like heat pumps, augmented by onsite renewables such as solar PV and battery storage. “When it comes to such strategies, building owners need the ability to make investment grade decisions using data and technology they can trust,” states Pettitt. “That’s exactly what we aim to provide.”

Only 31.6% of office buildings across the UK’s major cities currently have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) of C or higher. However, it’s crucial that asset owners look beyond their EPC to gain a true understanding of how energy efficient their buildings truly are, with even those rated at the higher end of the scale potentially performing far worse than their rating indicates. Pettitt points to a number of existing industry metrics, such as the UK’s NABERS sustainability rating scheme for office buildings, as a more accurate way to benchmark building performance with operational data. The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) and the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) Pathways also “help people plot their buildings’ decarbonisation plans against these industry-agreed trajectories to make sure that they are on track”, says Pettitt.

In terms of the gold standard, “the UK Green Building Council have set targets for energy use intensity for office buildings of 70 kilowatt hours per metre squared per annum from 2030”, says Pettitt. “By way of comparison, the average new office building in the UK is 160 kilowatt hours per metre squared. So that gives you a flavour of what needs to be done.”

Act now to avoid future challenges

In the realm of CRE, taking action on emissions often boils down to a nuanced discussion between building owners and tenants. Pettitt argues for a collaborative model, whereby costs – and indeed, benefits – are shared in a manner that aligns with lease arrangements and acknowledges the roles and responsibilities of each party. “The tenant has a role to play in minimising the carbon footprint through responsible utilisation of the building, while the owner must be receptive to the tenant’s needs, investing in improvements and advocating for green operations”, he says.

While the route toward mutual financial and environmental benefits may lack a one-size-fits-all solution, there’s also a shared advantage. Both landlords and tenants alike can benefit by employing IES technology. “Where can we insulate the building? Is it the roof, the walls or the floor? Is changing the glazing of the window, or adding solar PV, right for this building?” asks Pettitt. “The only way you’re going to really know accurate answers is via a deep data dive. Our digital twins incorporate live dashboards to provide a single pane view of performance across the building, offering actionable intelligence to guide both short-term operational optimisation strategies and longer term retrofit investments.”

Kicking the can down the road to 2050 is not a viable option, for business or government. “Buildings with low energy efficiency are exposed to both climate and financial risk. Climate risk can take the form of physical risks such as overheating, wildfires or flooding. While high demand on grid supplied electricity and fossil fuels also leaves buildings exposed to financial risks such as volatility in the energy markets and ability to secure preferential borrowing rates of green finance or insurance premiums,” warns Pettitt.

Now, with 57% of the world’s listed companies now reporting climate risk in line with five or more topics recommended by the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), Pettitt concludes, “decarbonising and future-proofing buildings now simply makes business sense.”

How tech has decarbonised commercial buildings

Creating a digital twin of a building can help to identify inefficiencies and enable the most effective strategies to heat and cool it dynamically

Climate change is no longer a future concern. Record-breaking global temperatures were observed in September 2023, which was 0.5°C hotter than the former record set in 2020. This negatively impacts our built environment, too. Almost all respondents (97%) to Deloitte’s ‘2023 commercial real estate outlook’ said their companies have “already been negatively impacted by climate change”, and about half said their operations have been affected, including disruption to business models and supply networks worldwide.

Many are understandably turning to technology to provide the solutions. As Chiara Essig, head of strategic sustainability services, EMEA, JLL, argues, it “just makes commercial sense – future-proofing buildings now will mitigate unplanned costs in the long run.” Deloitte also advises, “Technology is not a place where the real estate industry should be cutting back on spending”, citing “better efficiencies in the long term.”

The question is, what technology – and how? Decarbonising the built environment starts with gathering real-time operational data. With expert help, this can be stepped up into a digital twin, providing an invaluable digital picture of a building’s performance.

Identify inefficiencies

Within the CRE sector, states the UCL report ‘Towards Net Zero in UK Commercial Real Estate’, “digital data is being used to drive sustainability, resilience, and profitability by making better use of buildings with less energy use”. Creating a ‘digital twin’ of a building for example “helps to identify inefficiencies and enable the most effective strategies to heat and cool buildings dynamically according to their use profiles each day… this helps to reduce energy use by 20% or more”.

The Riverside Museum in Glasgow, for example, was found to be performing poorly against other properties in terms of energy management. A data investigation highlighted major energy consumers such as the HVAC (Heating, Ventilation & Air Conditioning) system, Air Handling Units (AHUs) and Chillers – a subsequent series of operational adjustments saw gas and electricity savings of 26% and 18% respectively, saving £52,300 annually – easily recouping the costs of the project.

Joey Aoun, Net Zero Implementation Lead at Savills Investment Management, also offers the example of the Cathedral Hill Industrial Estate in Guildford, UK. Its regeneration project, completed in 2023, comprises 13 light industrial and trade units. The occupiers significantly improved their energy use via “roof mounted solar PV coupled with battery storage, reporting negligible energy bills with some occupiers returning surplus energy back to the grid”, says Aoun. “New leases include mandatory obligations around data sharing and require occupiers to operate on a net zero carbon basis to encourage the continued sustainable efficiency of the estate in operation”. The owners are happy, too. Rents have more than doubled thanks to the regeneration, informs Aoun.

The need for companies to comply with sustainability commitments is driving this movement in the market, writes Ramya Ravichandar, Vice President, Product Management at JLL: “Clean tech will play a big role, from providing insight into daily use of assets, to modelling demand cycles to lower consumption – and ultimately, to change how we source and use energy.” She gives the example of smart sensors that detect office occupancy and optimise lighting and heating accordingly. Similarly, AI-powered windows and smart glass can now enable greater control over daylight lighting and temperature, automatically tinting glass while reducing reliance on lighting and air-conditioning.

In the City of London, 1 Exchange Square, originally built in 1987, was recently the site of one such ‘deep retrofit’, with triple glazed windows added, passive solar control to reduce reliance on cooling systems, green roofs and rooftop rainwater harvesting. McKinsey also identify that “technologies also make low-carbon heating and cooling systems, such as heat pumps and energy-efficient air conditioning, more cost competitive in many markets and climates.”

But ‘light retrofits’ can have a significant impact, too, via tweaks to existing technology. The UKGBC report ‘Delivering Net Zero: Key Considerations for Commercial Retrofit’ cites a multi-let office building in Central London that used IoT sensor technology to improve the ventilation control of its current system, delivering significant energy savings. It began with the installation of IoT sensors to gather the data, followed by upgrades to existing infrastructure, all with minimal disruption to the office operation. The project uncovered “increased energy efficiency, carbon reduction, improvement to wellbeing, productivity and thermal comfort.” The first phase saw an immediate 5% to 10% reduction in the electricity bill, with the refurbishment stage leading to a 11% to 24% reduction, with a 1.5 to 2.5-year payback.

Integrating complex AI systems to measure data on the building’s efficiency has been vital to retrofit Brett Ormrod has seen, too: “As a consequence, building performance can be optimised, resulting in energy and cost savings, and reductions in carbon emissions. What’s more, we’re not just seeing cost and environmental benefits, but wellbeing and comfort improvements too”. Decarbonising, it seems, leads to improved climate control in more ways than one.

7 steps to decarbonise whole-life performance of buildings

Whatever the stage of a building’s life, there are practical steps can you take to decarbonise it

‘Whole life’ carbon is defined by the UK Green Building Council as, “a building’s entire carbon impacts throughout its lifecycle”. This includes emissions from the “operation over the entire lifespan, and end of life impacts from replacement of materials and components.” So, whichever stage of a building’s life you are at, what steps can you take to decarbonise?

This is the “first step towards accelerating decarbonisation and optimisation for buildings”, says Brett Ormrod, Net Zero Carbon (NZC) lead for Europe, LaSalle Investment Management. From his work on LaSalle’s Net Zero Carbon Audit Programme, “we know that benchmarking and gathering granular energy data on our buildings and funds is vital to identifying where we can take low-cost, or even no-cost, measures for assets. For example, understanding the temporal demand for ventilation across a building has become crucial to optimise energy performance”.

Emily Hamilton, head of ESG at Savills Investment Management, also says that advanced technologies can aide the process, “including smart building automation systems, Proptech and data analytics, to monitor, optimise, and manage energy usage effectively… Data is the strongest ally in decarbonising the built environment.” As the old business saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure.

The UKGBC advises upskilling building facilities managers to help decarbonise building operations. This includes training on “in-use energy monitoring and reporting for the entire building portfolio and commit to sharing energy data regularly and transparently… disclosing on an annual basis the operational performance of assets.” Chiara Essig, head of strategic sustainability services, EMEA, JLL, adds that “good data is needed to really hold people to account… measures then need to be integrated into the asset business plans that the asset managers deliver. And property managers need to be engaged in such a way that buildings are used as efficiently as possible.”

Drive operational efficiency as far as you can with changes to user behaviour and the current systems that you have. “In other words, prioritising energy-efficiency improvements”, says Joey Aoun, net zero implementation lead at Savills Investment Management. These might include “upgrading HVAC systems, influencing occupant’s behaviour, and installing energy-saving lighting. These measures can significantly reduce a building’s footprint.” This is also known as ‘demand management’ – how people use a building can often be as important as the fabric of the building itself.

NABERS UK is a new system for rating the energy efficiency of office buildings. Like the efficiency star ratings that you get on your washing machine, NABERS provides a rating of office buildings from one to six stars. This helps building owners to understand their building’s performance versus other similar buildings – and tenants to make choices when looking for low carbon options. Design for Performance is the process whereby a developer or owner commits to design, build and commission a new office development or major refurbishment to achieve a specific NABERS Energy rating. Developers or owners need to contact a NABERS Licensed Assessor listed on GreenBookLive to register.

Given the split between landlord vs. tenant responsibilities – who decides who pays for decarbonisation upgrades and investments? The Better Buildings Partnership (BPP) describes Green Leases as “a lease with additional clauses included which provide for the management and improvement of the Environmental Performance of a building by both owner and occupier(s). Such a document is legally binding and its provisions remain in place for the duration of the term.” Clauses can cover metering, energy consumption, water consumption and discharge, waste generation and greenhouse gas emissions. Check out the BBP’s Green Lease Toolkit for more details.

Given that more than 80% of the buildings that will exist in 2050 already exist today, says Emily Hamilton, head of ESG at Savills Investment Management, “transform, reuse and retrofit projects have a key role to play in the decarbonisation of the built environment”. The UKGBC advises prioritising retrofit of existing assets over demolition and new build, given the substantial savings on resource use and embodied carbon. Industry guidance such as “PAS2038:2021 Retrofitting non-domestic buildings for improved energy efficiency” is available, covering a comprehensive set of recommendations for managing a retrofit process.

According to Kristy David, senior vice president, Clean Energy and Infrastructure, at JLL, solar power is the most popular choice of onsite renewables, but it’s “not one-size-fits-all. Often, we start by identifying the sites in a client’s portfolio with the greatest potential for on-site renewables… What’s more, we’re increasingly seeing tenants pushing their landlords for buildings that will help them deliver on their sustainability objectives. They’re making decisions on whether to stay or relocate based on issues such as the impact of premises on their scope 1 and 2 emissions, or whether a property has renewable energy provision.” She also advises combining the installation of on-site renewables with electric vehicle charging stations to drive down fleet costs and “help ready a business for the future”.

Data: the secret weapon to help commercial buildings reach net zero

The majority of businesses are poised to take action when it comes to complying with decarbonisation regulations in their country, but many lack the data or capabilities to comply