Greg Dyke, former head of the BBC, once famously referred to the corporation as “hideously white” and over the past two decades the label of “pale, male and stale” has been regularly applied to UK institutions and businesses.

Fortunately, many in the corporate world have taken significant proactive steps to redress the balance and yet the thorny issue of social mobility has, in regard to diversity and inclusion (D&I), been something of a poor relation, often overlooked and disregarded.

Diversity in the workplace matters

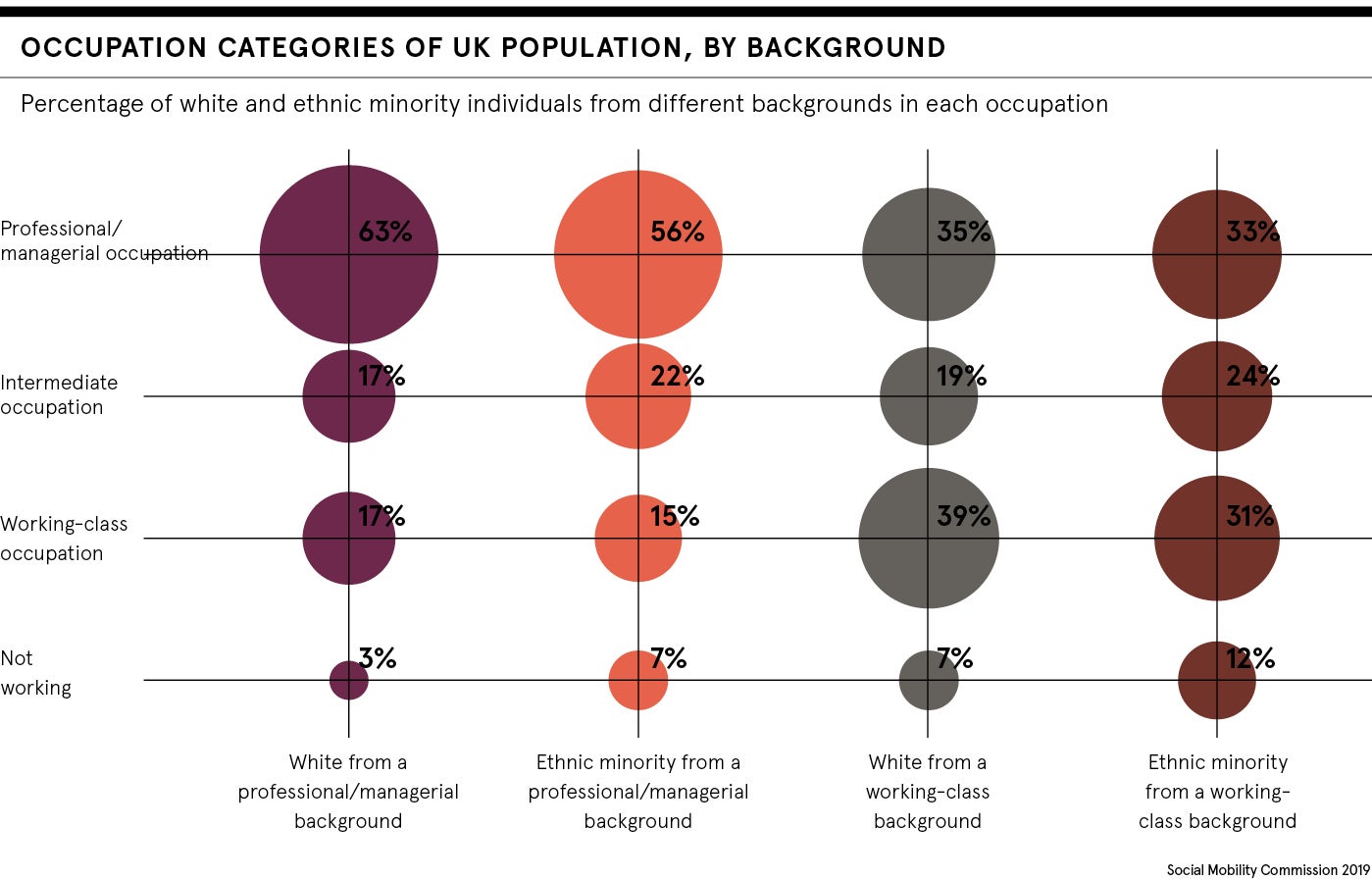

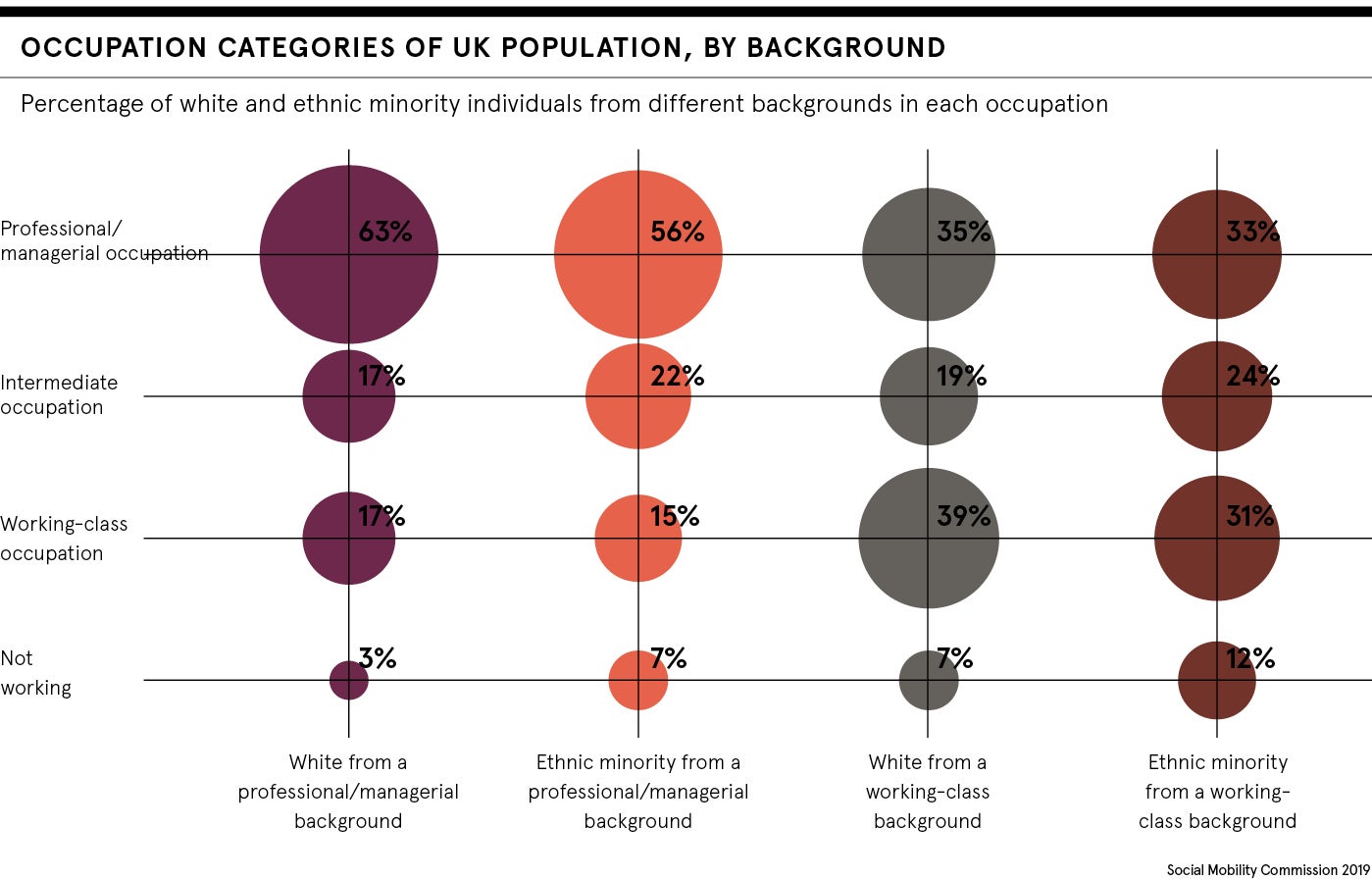

In 2019, the Social Mobility Commission reported that, over the past five years, social mobility in the UK had virtually stagnated and may have regressed, putting the UK’s progress behind only the United States and Italy as the worst in the developed world.

But while the situation may seem bleak, some progress is being made. Organisations dedicated to improving opportunities for those from disadvantaged backgrounds are beginning to make a difference and to engage successfully with business to help create a diverse workforce in an inclusive workplace based on diverse talent rather than privilege.

One such organisation is Making the Leap, a London-based organisation dedicated to improving the life chances of socio-economically disadvantaged working-class young people.

It’s privilege gaslighting. If you aren’t part of the group that is in charge, you can’t change things. It is not a level playing field

Founder and chief executive Tunde Banjoko highlights factors which may have overlooked. He points out that unlike sex, physical disability, religion, sexual orientation, ethnic diversity and marital status, social background is not a protected characteristic, resulting in there being no obligation on business to tackle a problem which is difficult to measure.

Recruiting the brightest and best

Banjoko maintains that socio-economic background is the most important characteristic to look at when assessing the likelihood of an individual’s future success and, while acknowledging there remains much to be done, is quick to congratulate those businesses that are now beginning to gather socio-economic data among their workforce.

No business wants to limit its talent pool and many are now starting to realise that positive policies surrounding recruitment and employee engagement in respect of background increase their chances of recruiting and maintaining the brightest and best.

Brixton Finishing School is an organisation set up to drive diversity and social mobility by offering free training for young people keen to work in the creative industries. Founder Ally Owen believes the structure of society presents its own specific challenges.

Owen points out that British society has historically been structured to benefit certain “in” groups of people and to disadvantage others. These others, which Owen refers to as the “out” groups, include those excluded by race, gender, accent, physical ability, neurodiversity and, of course, class.

She continues: “Class is a huge factor in limiting talented individuals from breaking through to ‘elite industries’. We tell ourselves that education is the key to social mobility and advancement. This is partly a myth and one that protects our system from change to a more inclusive structure.”

Owen references work by Dr Sam Freidman at the London School of Economics, which shows that those at Russell Group universities from a privileged background who achieve a second-class degree are much more likely to end up in elite professions than contemporaries from less privileged beginnings who went to the same university and bagged a first.

“Dr Freidman’s point is a depressing indictment of what our labour market is rewarding which, by the nature of this anomaly, is not the same as what our education system is rewarding. This ‘busts’ some of the myths around how education can be a ticket to social mobility,” she says.

“An individual from a group looking for social mobility can succeed and outpace those from a privileged background by jumping through all the academic achievement hoops we set them and win accolades only to be dismissed from the race at labour-market entry. This creates pools of highly qualified underutilised talent from a range of ‘out’ groups.”

Myths associated with “elite professions”

Affinity bias is one of the causes of this anomaly; having a more favourable opinion of someone like us is common. In hiring, this often means referring or selecting a candidate who shares our same race or gender, or who went to the same school, speaks the same language or reminds us of our younger selves. As the majority type within elite professions is white, public-school educated, and in senior positions male, this leads to a systemic favouring of this “in-group” type.

Another myth is that young people from certain backgrounds lack aspiration. This myth protects the structures that favour “in” groups from change by placing responsibility for the social mobility barriers on those who are trying to progress rather than those who have the power to change the systemic issues that keep them from doing so.

Owen says: “It’s privilege gaslighting. If you aren’t part of the group that is in charge, you can’t change things. It is not a level playing field. It does not matter how hard you work or how talented you are, if you are from a less privileged background, your race to success will be longer, harder and more likely to fail.”

Why there is room for optimism

There is, however, room for optimism. Organisations like the Brixton Finishing School and Making the Leap are achieving measurable success, while recruitment companies specialising in social mobility, such as Rare Recruitment, are making real inroads into the highest echelons of the corporate world, boasting top law firms and corporate services companies among their clients.

Unconscious bias, that most insidious of prejudices, is being acknowledged and addressed, and an increasing number of D&I mission statements are conceding much more needs to be done to spread opportunity more widely.

Similarly, switched-on corporates with a commitment to diversity have the opportunity to be rewarded for creating an inclusive culture and improving social mobility within their organisations. The roll call of winners at the UK Social Mobility Awards includes leading employers from both the private and public sectors, while the long-established European Diversity Awards added a Social Mobility Initiative of the Year award in 2017, attracting entrants from across the continent.

While doling out gongs at a black-tie event may not speak directly to the disadvantaged, it does at least send the message that social mobility matters.

Diversity in the workplace matters

Recruiting the brightest and best

Myths associated with “elite professions”