UK productivity languishes at the bottom of the G7 league table, 20 per cent lower than average, and falls behind many other Western countries.

“The gap has always been there, but it’s worse since the financial crisis,” says Anna Valero, research economist in growth at the London School of Economics. “We are about 30 percentage points behind France, Germany and the US.”

Labour productivity – output per hour worked – is critical to economic success. The government estimates if the UK could match the US’s productivity it would raise GDP by 31 per cent. But the UK’s productivity puzzle remains stubbornly unsolvable. Why? Several different pieces must be considered.

Engagement at the core

When chancellor George Osborne unveiled his Productivity Plan in 2015, it focused on tax systems, infrastructure and cutting red tape, as well as closing the skills gap via an apprenticeship levy. The plan addresses some of what Ms Valero calls long-standing problems, such as skills shortages and underinvestment in infrastructure, but doesn’t address other key areas, chiefly those related to people management.

Eugenio Pirri, vice president of people and organisational development at Dorchester Collection, feels Mr Osborne missed a critical point. “A fatal flaw is his lack of focus on engagement,” he says. “Businesses can never be productive if people are not productive; people can never be productive if they are not engaged.”

Nita Clarke, director of the Involvement and Participation Association and co-founder of Engage for Success, agrees. “High levels of engagement equal high levels of productivity,” she says. “If someone feels motivated, listened to and respected, they will be more agile, innovative and find ways around problems.” Autonomy and empowerment are key.

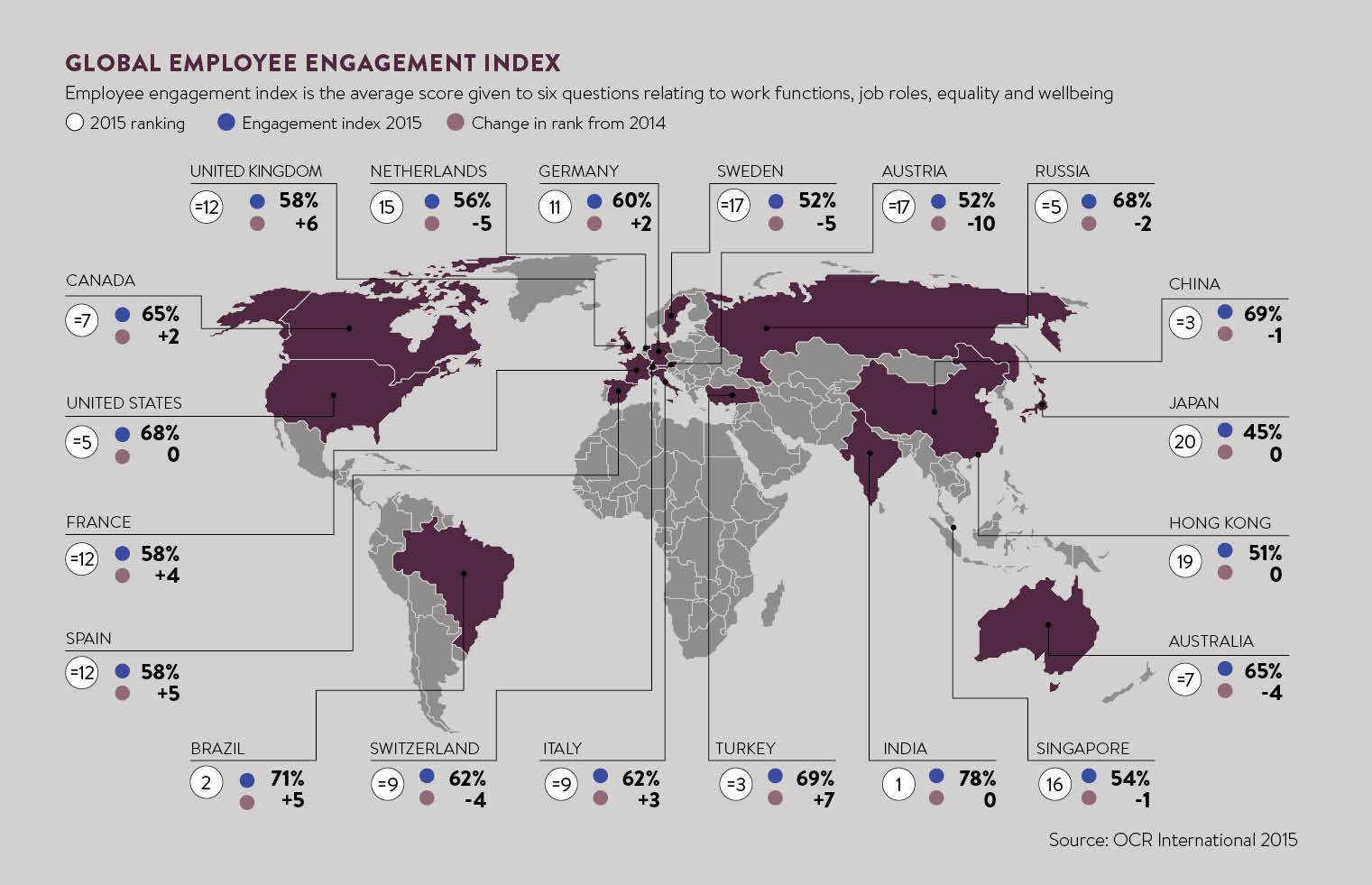

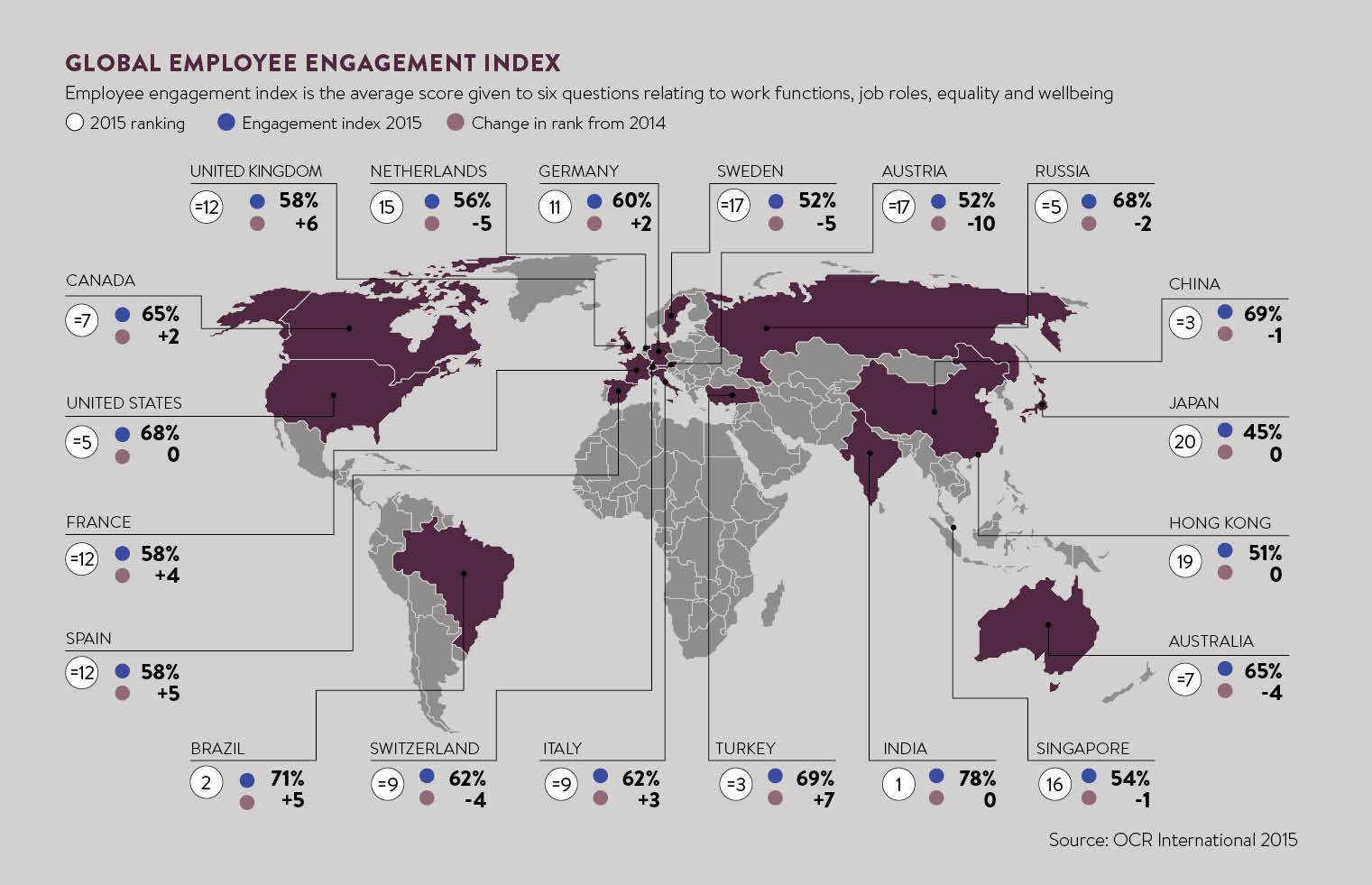

Research from HR consultancy Purple Cubed found 70 per cent of business leaders see a link between engagement and productivity. Yet the UK’s record on employee engagement is as bad as its productivity score. Only 58 per cent of the UK workforce is engaged, according to data from OCR International.

“The UK lags significantly behind,” says Sam Dawson, director and UK head at Hay Group Insight. “Where engagement is strong there is often a greater sense of company direction, leadership and employee buy-in. Companies with high engagement and enablement outperform others on productivity by 50 per cent.”

The significance of leadership

However, focusing on engagement alone as a panacea for our productivity ills would be a mistake, warns Professor Sir Cary Cooper of Manchester Business School, an expert in organisational psychology and health. “Engagement is only one piece of the puzzle,” he says. “We need to look at how people are managed. Do we have socially and interpersonally skilled managers from shop floor to top floor?”

Evidence would suggest not, says Ben Willmott, head of public policy at the Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development. “The quality of management and leadership in the UK falls below our global competitors,” he says, citing a Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) report, Leading the Way: Boosting Leadership and Management in Small Firms.

The FSB paper finds that while the UK has a “good share of businesses in the top quartile” for management and leadership, there is a long tail reaching well into the bottom quartile. In summary, the UK has a larger share of firms with poor quality management practices, resulting in lower productivity.

“Owner-managers often have little experience of leading and managing people, limited resources and limited time to think strategically about investing in people,” says Mr Willmott. “That leads to poor engagement and productivity.” He advises more government support for small businesses in this area, citing Germany’s Mittelstand as an exemplar.

Sweden is considering legislating for a 30-hour week to increase productivity

Professor Cooper also advocates the importance of emotionally intelligent managers. “We have fewer people doing more work, and we need managers not just with technical competencies, but people skills and high EQ [emotional quotient] levels,” he says.

Eliminating the ‘long hours’ culture

Another way to raise productivity sounds counterintuitive – do less to get more. “We work longer hours than our Western counterparts, but we are less productive and less engaged,” says Claire Fox, global HR director at Save the Children.

Professor Cooper adds: “Germany has the highest levels of productivity [in the G7] and only works 35 hours a week. In the UK we work between 45 and 60 hours a week.”

Ms Fox says: “Our working culture of long hours and unmanageable workloads is not sustainable, and it’s contributing to our lack of competitiveness. [UK leaders] are focused on doing more with less, but they need to understand this is not the same as productivity. Halving the team and doubling the work does not mean productivity will increase.” Sweden seems to have realised this and is considering legislating for a 30-hour week to increase productivity.

Tackling technology overload is also critical, says Professor Cooper. In Germany, some corporates already do so, including Daimler and Volkswagen, which delete e-mails received during a holiday and shut down e-mail servers during out-of-office hours, respectively.

There are many pieces to the UK’s productivity puzzle. Fitting them together will not be easy, but one thing is clear that good people management practices must be at the heart of the UK’s approach. In the words of Ingrid Eras-Magdalena, senior vice president of global HR at Belmond Hotels: “Without people, there is no productivity.”

PRODUCTIVITY LESSONS FROM AROUND THE WORLD

France

According to Ingrid Eras-Magdalena, senior vice president of global HR at Belmond Hotels, France is characterised by “high job security and relatively fewer working hours per day”. “The bond between employee and employer is stronger and long lasting,” she adds. The French government is also tackling e-mail overload.

Germany

The Germans are productivity exemplars, thanks to their longer-term business view. Family and small and medium-sized businesses in the Mittlestand benefit from professional management and collaboration. The apprenticeship system is the world’s best, resulting in a highly skilled workforce. Employees work the shortest hours in the G7.

The Germans are productivity exemplars, thanks to their longer-term business view. Family and small and medium-sized businesses in the Mittlestand benefit from professional management and collaboration. The apprenticeship system is the world’s best, resulting in a highly skilled workforce. Employees work the shortest hours in the G7.

United States

Ms Eras-Magdalena and Professor Sir Cary Cooper of Manchester Business School debate whether the US model of job insecurity and few workplace benefits is one to emulate, although it does lead to high outputs in the short term. However, investment in digital innovation, particularly in Silicon Valley, has helped the US stay ahead.

Ms Eras-Magdalena and Professor Sir Cary Cooper of Manchester Business School debate whether the US model of job insecurity and few workplace benefits is one to emulate, although it does lead to high outputs in the short term. However, investment in digital innovation, particularly in Silicon Valley, has helped the US stay ahead.

Norway

According to data from the Conference Board and Eurostat, Norway is the most productive nation in the world. Much of this is thanks to the Nordic leadership style, which a Hay Group report on engagement in those countries described as one where “trust, consensus, collaboration and autonomy are the norm”.

According to data from the Conference Board and Eurostat, Norway is the most productive nation in the world. Much of this is thanks to the Nordic leadership style, which a Hay Group report on engagement in those countries described as one where “trust, consensus, collaboration and autonomy are the norm”.

The Netherlands

The Dutch have long holidays and shorter working hours, yet are more productive than the British, backing up Professor Cooper’s view that “getting rid of our long hours culture is the answer”. One technology company has even made it impossible for employees to work late, winching their desks to the ceiling at 6pm.

The Dutch have long holidays and shorter working hours, yet are more productive than the British, backing up Professor Cooper’s view that “getting rid of our long hours culture is the answer”. One technology company has even made it impossible for employees to work late, winching their desks to the ceiling at 6pm.

Engagement at the core