When Jennie Allen saw her GP with abdominal pain and bloating, the symptoms were initially put down to a bladder infection, then coeliac disease.

But with a mum who had died of breast cancer aged 50, Jennie was determined to get to the root of her pain and constant tiredness.

Despite a second opinion from a different GP, who believed Jennie might have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), the then-51-year-old business owner insisted on being checked for ovarian cancer and was ultimately diagnosed with the disease.

“It may be easy to get wrong and testing can throw up false positives or negatives, but it’s got to be better than the alternative,” says Jennie.

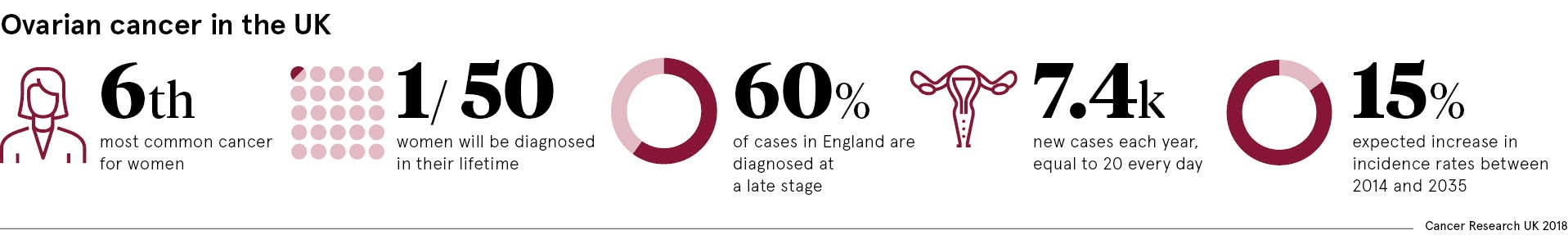

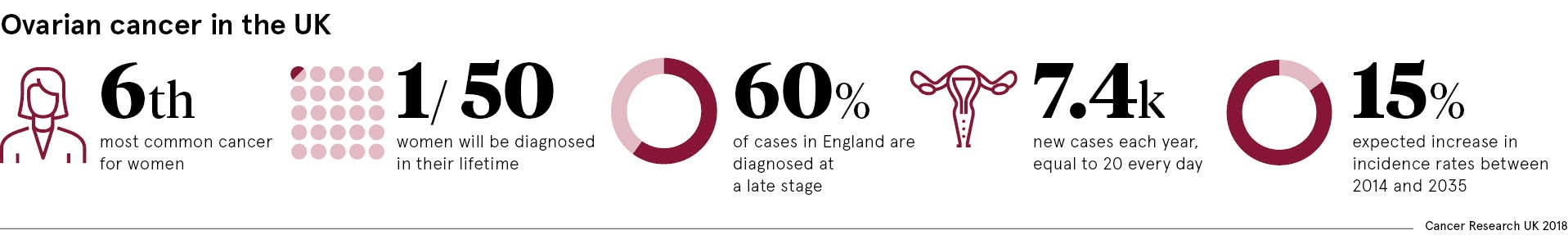

She is not alone. Almost half of women wait three months or more from first visiting their GP to getting a correct diagnosis and around 4,100 die each year from the disease.

Yet more than 90 per cent of women will survive ovarian cancer for at least five years if diagnosed early.

“It’s a difficult world for GPs because the majority of women present with symptoms that resemble IBS,” says ovarian cancer specialist Gordon Jayson, professor of medical oncology at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

“Improving survival comes down to awareness and education, early diagnosis, and not giving up on very sick patients. We need to develop a UK-wide strategy to deal with this.”

Steps being made to raise awareness, but not enough has been done yet

While a Department of Health spokesman said there are currently no plans for a dedicated ovarian cancer strand in its Be Clear on Cancer campaign, charities including Target Ovarian Cancer and the Eve Appeal are working to raise awareness of the disease and its symptoms.

Meanwhile, Target Ovarian Cancer’s education modules, developed with the Royal College of GPs and BMJ, have so far been delivered to more than half of GPs.

GP Vicki Barber’s own mother died of ovarian cancer in 2014 and she trains colleagues at national events to ensure symptoms like persistent abdominal bloating and pain, feeling full, and urinary issues are not misdiagnosed.

“No GP wants to miss a diagnosis of ovarian cancer,” says Dr Barber. “It’s important we all work hard to ensure more GPs are aware of the symptoms and correct pathway to diagnose ovarian cancer earlier.”

Progress made in life-changing ovarian cancer research

In the research community, potentially life-changing studies could make a difference to ovarian cancer detection.

Launched in August, the ALDO (avoiding late diagnosis in ovarian cancer) project will check around 2,000 women every four months using an algorithm known as the ROCA test to assess changes in blood chemical CA125, which typically rises in ovarian cancer.

Although the trial is specifically for women who carry faulty BRCA genes with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer, like actress Angelina Jolie, who underwent a double mastectomy and removal of her ovaries, the regular surveillance could give those women more choice about when to undergo surgery, says the project’s clinical director Adam Rosenthal.

Dr Rosenthal, consultant gynaecologist at University College London Hospitals, believes early detection through annual screening for the wider population could be just a few years away.

Almost half of women wait three months or more from first visiting their GP to getting a correct diagnosis

More evidence is needed before national programme is introduced

While initial results from the UK collaborative trial of ovarian cancer screening (UK CTOCS) of more than 200,000 women showed screening might prevent one in five deaths, the study did not reach the evidence threshold needed to make it scientifically significant.

However, the project has been extended to gather further evidence on the long-term impact of screening on ovarian cancer deaths.

“The whole world is waiting on this,” says Dr Rosenthal. “It’s very possible UK CTOCS will show a statistically significant mortality reduction and at that point the NHS National Screening Committee would have to accept that for the first time ever we have evidence that screening the general postmenopausal population for ovarian cancer once a year could save lives.

“The question then is whether introducing a national programme to every woman aged 50 to 70 is cost effective.

“We’ve chipped away at ovarian cancer survival, but the only way to make a big difference is by detecting it much earlier, preferably at a pre-cancerous phase like with cervical cancer screening. There needs to be a shift in emphasis and political-level realisation that prevention is cheaper than cure.”

Long way to go in raising ovarian cancer’s profile

Dr James Brenton, senior group leader at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, says: “When we look at the dismal outcomes for ovarian cancer, it’s important to realise there is a combination of early spread, genomic chaos and difficulty in diagnosis.

“Early diagnosis remains the Holy Grail. Blood tests are going to be key and, taking into consideration risk factors, are a relatively simple and cheap way to pick up ovarian cancer much earlier.”

Prime minister Theresa May announced plans this month for detecting three out of four cancers at an early stage by 2028, by overhauling screening, including same-day testing centres nationwide, providing new investment in diagnosis technology and boosting research.

However, statistics show ovarian cancer research funding has dipped over the past five years, despite the disease projected to rise 15 per cent in the UK by 2035 to around 8,500 new cases each year.

Annwen Jones, chief executive of Target Ovarian Cancer, concludes: “We need to change the nihilistic mindset about the disease, brought on by low awareness, low funding, late diagnosis and low survival rates, because if we don’t invest in more research then it is a vicious circle.”

Steps being made to raise awareness, but not enough has been done yet