When it comes to detecting oral cancers, dentists are on the frontline against these life-threatening diseases. That is why many consider it a major concern that the vaccine offering protection against the human papilloma virus (HPV), the leading cause of some throat and mouth cancers, is only offered free in the UK to school-age girls and not boys.

When it comes to detecting oral cancers, dentists are on the frontline against these life-threatening diseases. That is why many consider it a major concern that the vaccine offering protection against the human papilloma virus (HPV), the leading cause of some throat and mouth cancers, is only offered free in the UK to school-age girls and not boys.

The British Dental Association (BDA), other bodies representing healthcare professionals and patient groups have lobbied for a gender-neutral approach to halt the rapid increase in HPV-related cases. A recent poll found that the overwhelming majority of dentists and GPs would want their son to get the jab, and the government’s vaccine programme extended to boys.

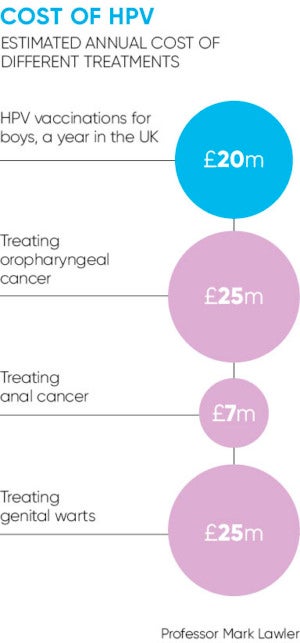

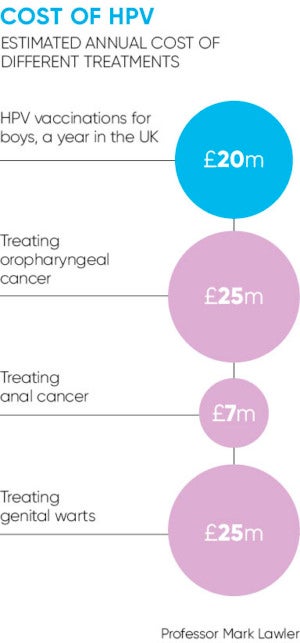

Yet any prospect of this happening is remote. The UK’s independent expert panel on vaccine issues, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), concluded this month that expanding the scheme was unlikely to be cost effective. A final decision will be made in six weeks, although the JCVI is unlikely to reconsider.

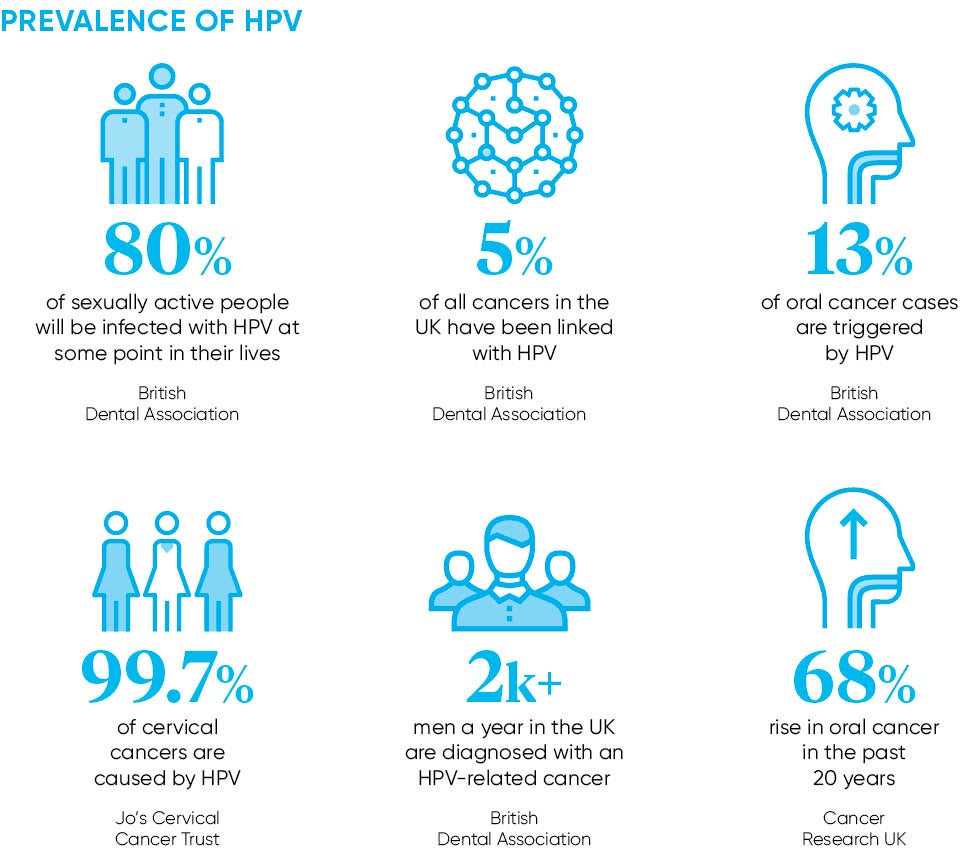

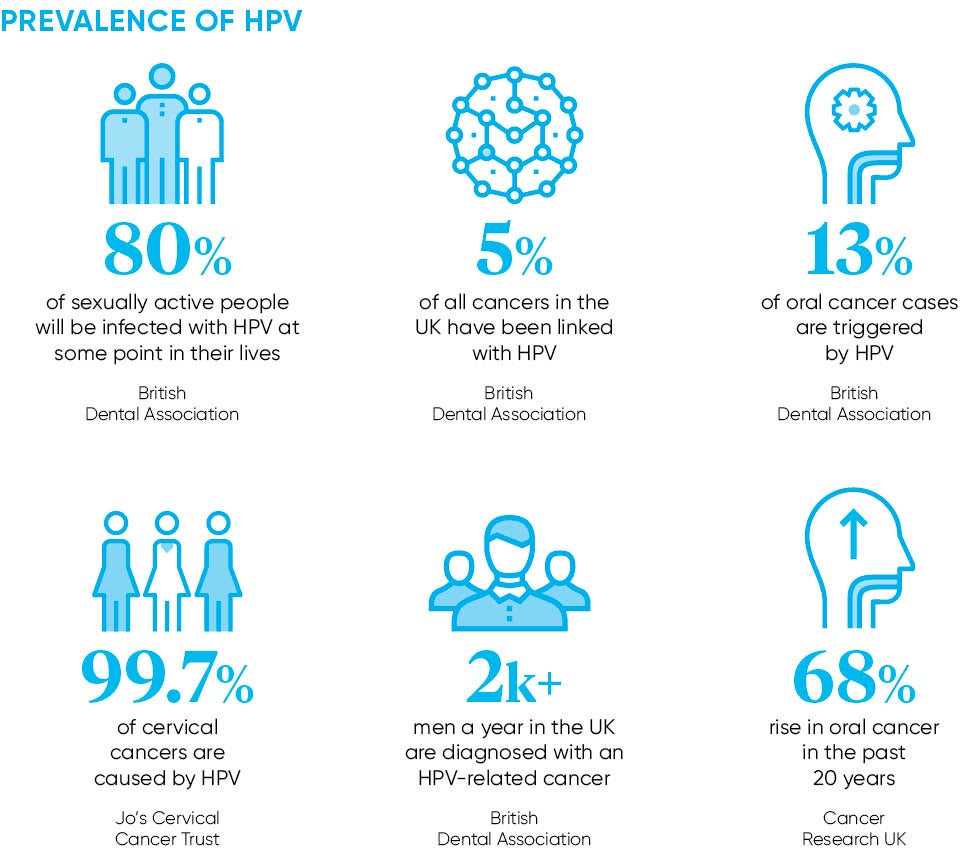

This is despite oropharyngeal cancer (OPC), a disease that starts in a part of the throat, being four times more likely to occur in men than women. Worldwide projections indicate that OPC will be more common than HPV-related cervical cancer in women by 2020, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In addition, HPV which is spread through sexual activity has been linked, according to the National Cancer Institute, to 5 per cent of cancers worldwide, including penile and anal. The virus is also to blame for 48,000 genital wart diagnoses in British men every year.

The outcome of the JCVI review effectively means that 400,000 school-age boys are left at risk, according to Mark Lawler, from Queen’s University Belfast. He says a universal programme could prevent cancer, and reduce the cost to the NHS and to the country.

“This is a huge wasted opportunity. We talk about preventing HPV-related cancer, but we’re not doing it with boys,” adds Professor Lawler. “It’s a health inequality when something that works in both sexes is only used in one. As well as a human cost, cancer impacts the economy because people can’t work.”

HPV policy

The HPV vaccination programme was implemented in 2008 with girls targeted on the grounds that protection was principally a female issue. The objective was to prevent infection from two high-risk types of HPV that cause at least 70 per cent of all cervical cancers. This was before the link between the virus and oral cancers, including in men, was fully known.

In theory, boys are protected by so-called “herd immunity”. Vaccinating women reduces the risk of men becoming infected. But this has potential limitations given vaccine uptake among girls has dropped over the past year and variations exist across the country. This approach also does not take into account men from ethnic communities where again the rate of take-up is low. Neither does it protect boys who will go on to have sex with men, although males attending sexual health clinics can now get the vaccine for free.

Dr Andrew Green, British Medical Association’s GP Committee’s prescribing lead, says: “It would be impossible and unethical to identify those boys who will go on to have sex as adults with other men. The only sensible way is to immunise all boys – it’s an equality issue.

It’s a health inequality when something that works in both sexes is only used in one

“Boys get the MMR jab to reduce the spread of the rubella virus, which is dangerous for pregnant women. It’s bizarre that this hasn’t happened with HPV.”

The policy not to extend the vaccination programme means parents with sons may go private. The pharmacy sector has been gearing up by extending availability of the jab. In March, Superdrug said it would be available in 62 stores for nine to twenty six year olds, then Boots announced it would offer the vaccination service in 68 outlets to males and females aged 12 to 44.

“This helps ensure more men and boys across the UK have access to this important vaccination,” says Richard Bradley, Boots UK pharmacy director. “It’s an example of how community pharmacists can use their clinical skills to support patients’ health in locations and at times convenient to them, and complements existing NHS vaccination provision.”

This service comes at a considerable price though. Boots is charging £300 for parents with sons aged 12 to 14 and £450 for 15 year olds or over, a cost only afforded by affluent parents. Therefore, a consequence of the NHS not funding the jab for boys will be a health divide between the haves and have-nots, says Oral Health Foundation chief executive Nigel Carter.

“Parents of boys could pay for the vaccine, but it will literally come at the price of increased inequality,” he says.

A possible way forward is a legal challenge on the grounds of gender bias. Campaign group HPV Action has indicated they are considering this step under equality laws, unless the JCVI changes its mind. The fight is not over, says BDA chair Mick Armstrong: “The state has a responsibility to offer the best possible defence against HPV to all our children – and that includes boys.”

HPV policy