The ambition of stroke science has created a golden age of treatment where some patients, who once faced a lifetime’s disability following an attack, can walk out of hospital within days.

The ambition of stroke science has created a golden age of treatment where some patients, who once faced a lifetime’s disability following an attack, can walk out of hospital within days.

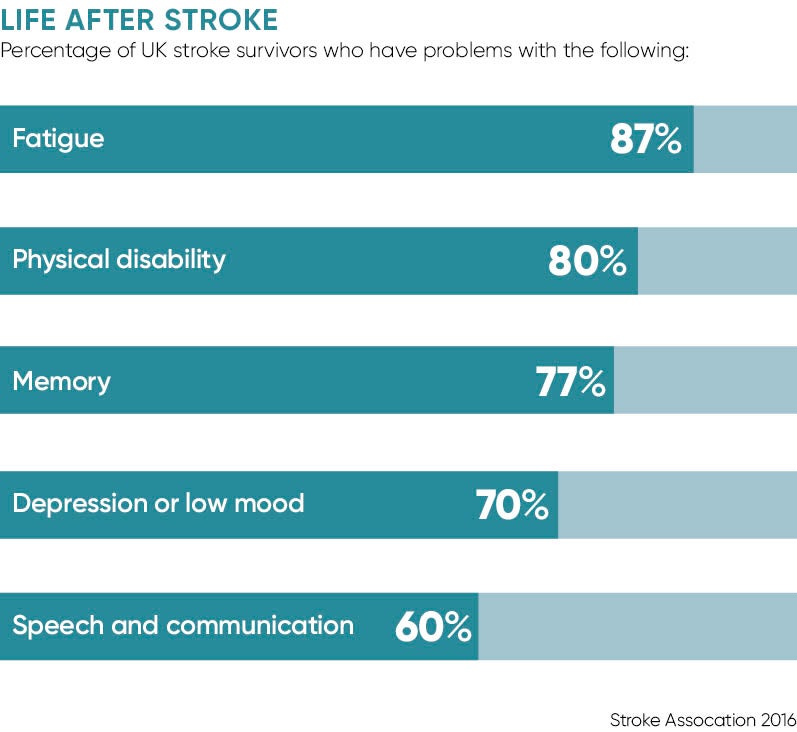

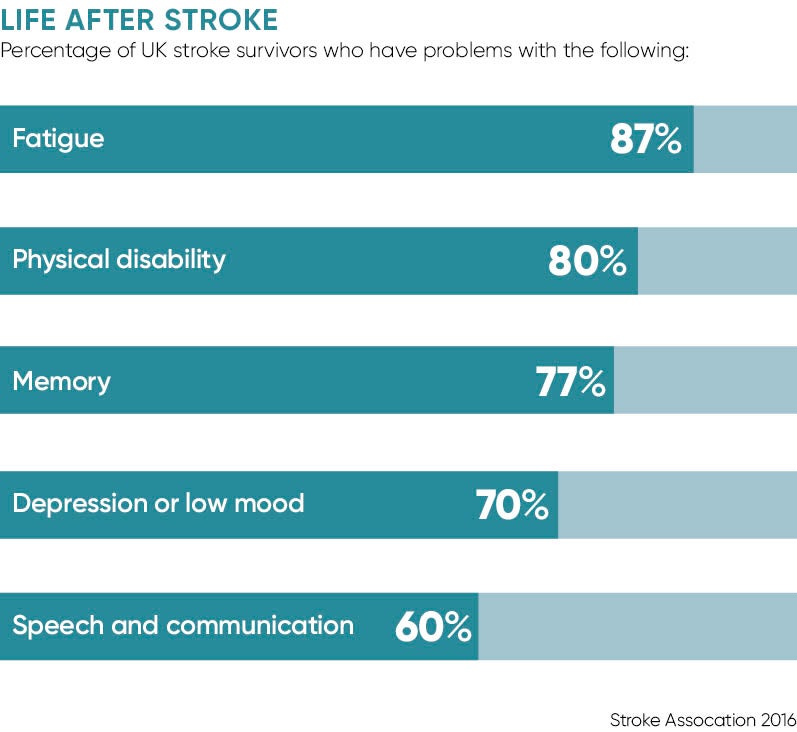

Advanced techniques and streamlined medical workflow are changing outcomes and it is easy to become hypnotised by the triumphs in the operating theatre. But four out of ten of the UK’s 1.2 million stroke survivors leave hospital requiring help in their homes where daily struggles can have a corrosive and expensive impact as almost a third receive no social service visits, according to the Stroke Association.

It is accepted that physiotherapy and support which covers speech, language and psychological help are most effective when delivered early and consistently, but a 2016 survey reported that 45 per cent of patients felt abandoned after they left hospital and only 31 per cent got the recommended six-month case review.

“What we see from reports is that standards in hospitals are steadily improving, which is great, but stroke survivors tell us that things fall down when they are discharged from hospital,” says Juliet Bouverie, chief executive of the Stroke Association.

“Sadly, aftercare is lagging behind and in some areas provision is shocking. It is disappointing how little support is there for them.

“Stroke is a recovering condition unlike a lot of neurological conditions, which are degenerative, so there is a real, compelling case for investing in support therapies early which reduce the cost to the state and enable people of working age to get back to work.

“We have people leaving hospital quite quickly after an incredibly life-changing event with very severe disabilities, who are not getting essential rehabilitation services and psychological support – in some parts of the country the waiting time for psychological help is five months when the target is 14 days. There are also huge regional variations.”

Stroke aftercare

Reports show a disconnect between hospital and community performances, and opportunities to reduce the £9-billion annual economic burden of stroke are being lost. Informal care costs are estimated to be £2.42 billion annually, while benefit payments for stroke patients have reached more than £800 million a year. Annual productivity losses due to care, disability and death are estimated at £1.33 billion.

Physiotherapy, the first step on the road to recovery, is limited in some areas. Karen Middleton, chief executive of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, says: “Patients feel abandoned after they leave hospital and have described it as like falling off a cliff. We hear a lot about progress in hospital treatment, but what happens afterwards? Too many people are struggling and suffering at home, hidden from view, because support and care packages are not there for them.

“It is an absolute false economy to do this because, without help early on, stroke survivors need more help long term.

“Physiotherapy is essential to that recovery and we talk about not just adding years to their lives, but also adding life to those years. But this part of stroke is not glamorous; it is not where you find the TV cameras.”

It is a view echoed by Dr Martin James, consultant stroke physician at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. He says: “There has been a lot of progress over the last ten years since the National Stroke Strategy was introduced and there is a lot of excitement at the acute end, but the caring for stroke survivors in the community has not really been implemented successfully.

Too many people are struggling and suffering at home, hidden from view, because support and care packages are not there for them

“It means that a lot of people living in the community with the disabling consequences of stroke still aren’t receiving the services they need. It is quite expensive long term to look after someone with disability in the community, so it is cost effective to have interventions that reduce their reliance on services, such as the number of times they see their GP.”

Dr James, clinical lead for the Royal College of Physician’s Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme, adds that the repercussions are being felt across the social care budget. “One in three people who end up in a residential or nursing home are having to go there because they have had a stroke, so it is a huge contributor to long-term social costs. Social care has not had its budget protected in the way healthcare has. A lot of this burden falls on individuals and families,” he says.

The early supported discharge scheme, which offers a full range of specialist support for six weeks, can save £1,600 on social care costs per patient, but its provision is patchy and campaigners believe too many patients slip through the net and their recovery is stalled, increasing the burden on families and the state.

“People cherish their independence after a stroke and we should be doing everything we can to give them that,” says Dr James.

Ms Bouverie concludes: “We are seeing a loss of momentum in stroke and long-term rehabilitation has been deprioritised when it is clear that if you intervene early the burden of disability is reduced and stroke survivors are less of a cost to the state long term.”

Stroke aftercare