It is impossible to define the size of the ideal city. Consider the Japanese capital Tokyo and its busiest railway station Shinjuku. The equivalent of the entire population of Australia, around 24.5 million people, passes through the terminal on a weekly basis. This proves a vast number of people can be accommodated in one place, so long as the right kind of planning and infrastructure is in place.

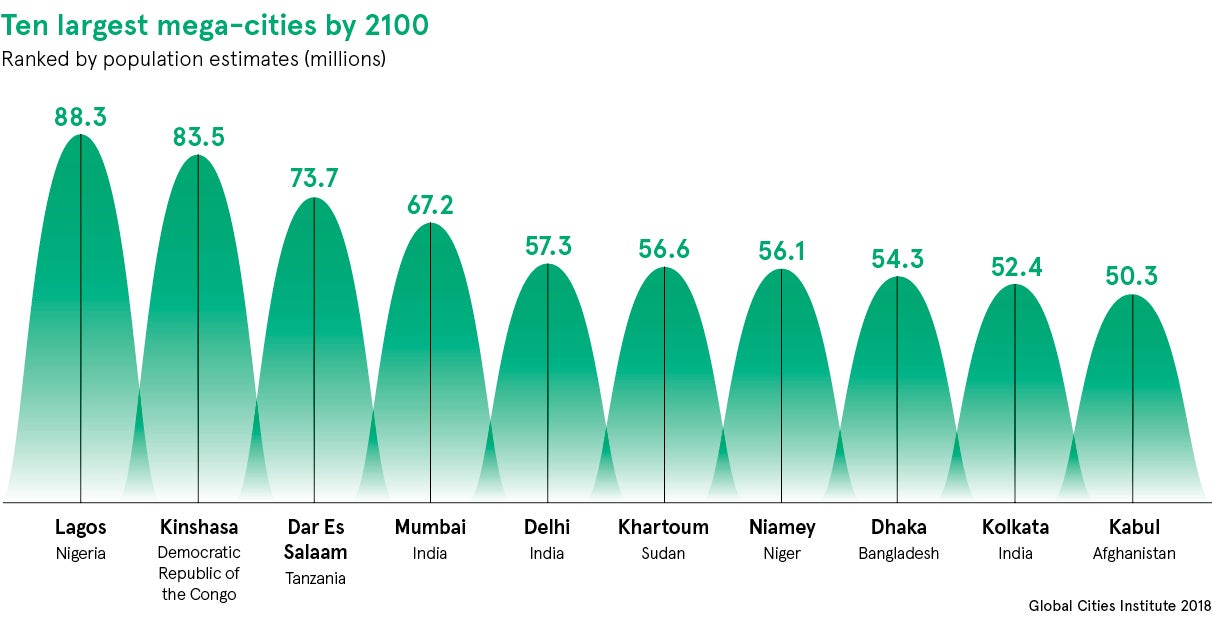

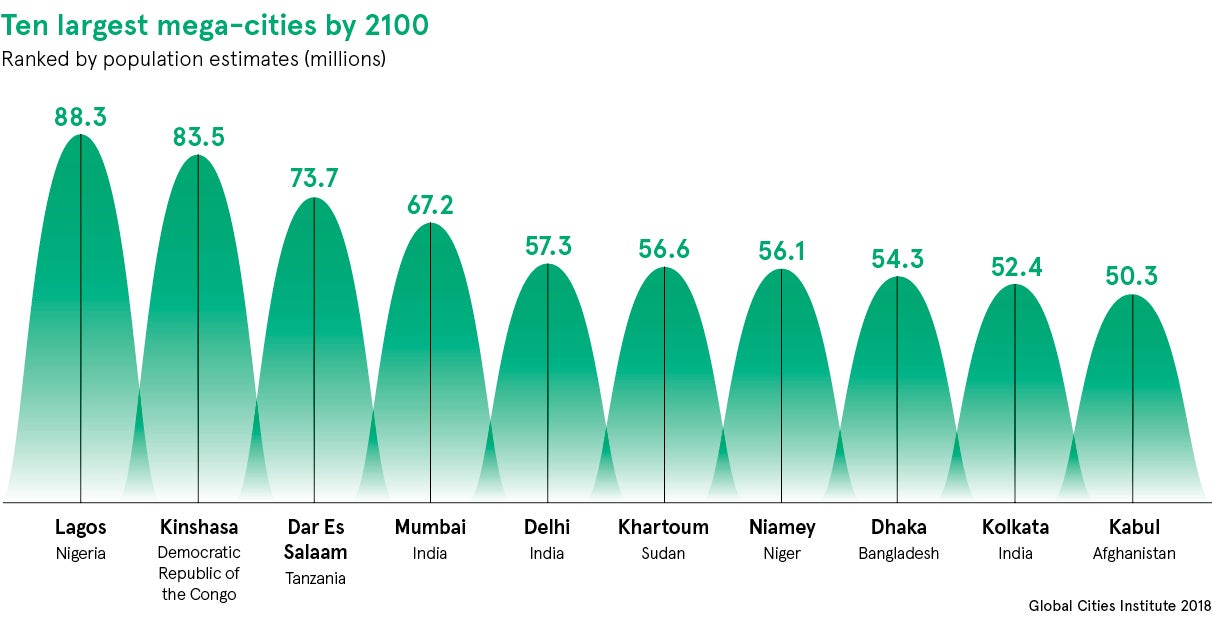

Rapid urbanisation does, however, pose enormous challenges. More than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas. According to the United Nations, the proportion is set to rise to almost 70 per cent by 2050. By then the planet is expected to be home to 43 megacities of more than ten million inhabitants. Those in charge of our ever-swelling cities have a huge amount of work ahead to make sure they can cope with this unstoppable influx of people.

Radical changes will be required to meet the demands on transport, housing and energy supply, to improve air quality and waste management processes, and to prepare urban settlements for extreme weather and the increased risk of flooding brought on by climate change.

Urbanisation offers new opportunities to improve our existing cities

The scale of action required is daunting, but urbanisation should, in theory, inspire innovation. So are we entitled to be optimistic about the chances to improve the way our cities function? What can the most imaginative and responsible businesses do to make cities more liveable and more ecologically sustainable?

Because emerging cities are still expanding, and because some areas are still a blank slate, it gives you a great opportunity to grow in a more sustainable way

Antonia Gawel, head of the Circular Economy Initiative at the World Economic Forum, believes many of the large, emerging cities around the world have the opportunity to learn from the past and do things differently from the planet’s long-established industrial cities.

“Because emerging cities are still expanding, and because some areas are still a blank slate, it gives you a great opportunity to grow in a more sustainable way,” Ms Gawel explains. “It’s about making sure the right infrastructure is in place, but it’s also about having the right systems, the right business models and the right kind of engagement with consumers to encourage behaviour change.”

New infrastructure at the top of the agenda

Many rapidly growing cities, especially those in Africa and Latin America, will have to bridge worrying infrastructure gaps. City governments will have to raise extra revenue and commit the funds to major transport, energy and telecommunications projects if they want to bring in businesses investment. But money is only one part of the urbanisation puzzle.

Ms Gawel believes that the partnership between government and business works best when they are both working towards clear and definite objectives. “The challenge is to make sure all the actors are trying to rethink a system, perhaps based on a particular target around food waste or whatever it might be,” she says. “You need vision to achieve a goal, otherwise it won’t happen.”

The way we build things will have to change. The construction industry is currently the largest single consumer of raw materials on the planet, so it’s vital old buildings are now viewed as a resource, rather than waste product. In Denmark, leading companies are recycling materials taken from abandoned buildings and using them to construct new ones in the capital Copenhagen.

“It’s exciting,” says Ms Gawel. “It’s an industry that has started thinking about the circular economy and how you begin to reuse materials. There is a chain of actors you need to bring along, from engineers to architects to construction companies, and the whole industry needs to be given the right incentives by government.”

Tackling waste and water in emerging cities

Rethinking waste systems remains another key priority for cities dealing with rising consumption. There are encouraging things happening in India, where there is a growing trend toward road-building using recycled plastic, and data intelligence companies are helping city authorities identify exactly what is happening to different forms of waste.

Cities such as Delhi and Mumbai still have a large informal sector of pickers salvaging reusable or recyclable material from rubbish dumps. Ms Gawel hopes waste management companies can work with these slum dwellers to make the separation of materials more efficient and provide new opportunities for those doing the work.

“If we want to professionalise and scale up the recycling, it requires a delicate collaborative approach,” she says. “You need government, companies, community leaders and social entrepreneurs to work together.”

Managing water resources more sustainably is another vital task related to rapid urbanisation. China’s “sponge city” initiative has seen the government partner with private developers to invest in projects to prevent flooding and ease pressure on groundwater sources. New wetlands, plant-covered rooftops and permeable pavements have been created to help absorb and reuse rainwater.

Urbanisation can be seen as a positive sign of growth

Ms Gawel hopes such projects can also make cities more resilient to climate change. “The current reality [of climate change] that is hitting home in certain cities means the conversation about resource conservation and infrastructure adaptation work is now happening in all sorts of places around the world,” she says.

Despite all the complications created by rapid urbanisation, it can also be a positive sign of economic growth. One of the biggest challenges, however, is making sure the benefits are widely shared. Failure to think about social cohesion and the needs of the poorest newcomers will result in growing inequality, burgeoning slums and even civil unrest.

More than ever, the urban environment will be the engine of the global economy in the century ahead. The planning challenges are immense, but the opportunities are just as big.

Urbanisation offers new opportunities to improve our existing cities

New infrastructure at the top of the agenda