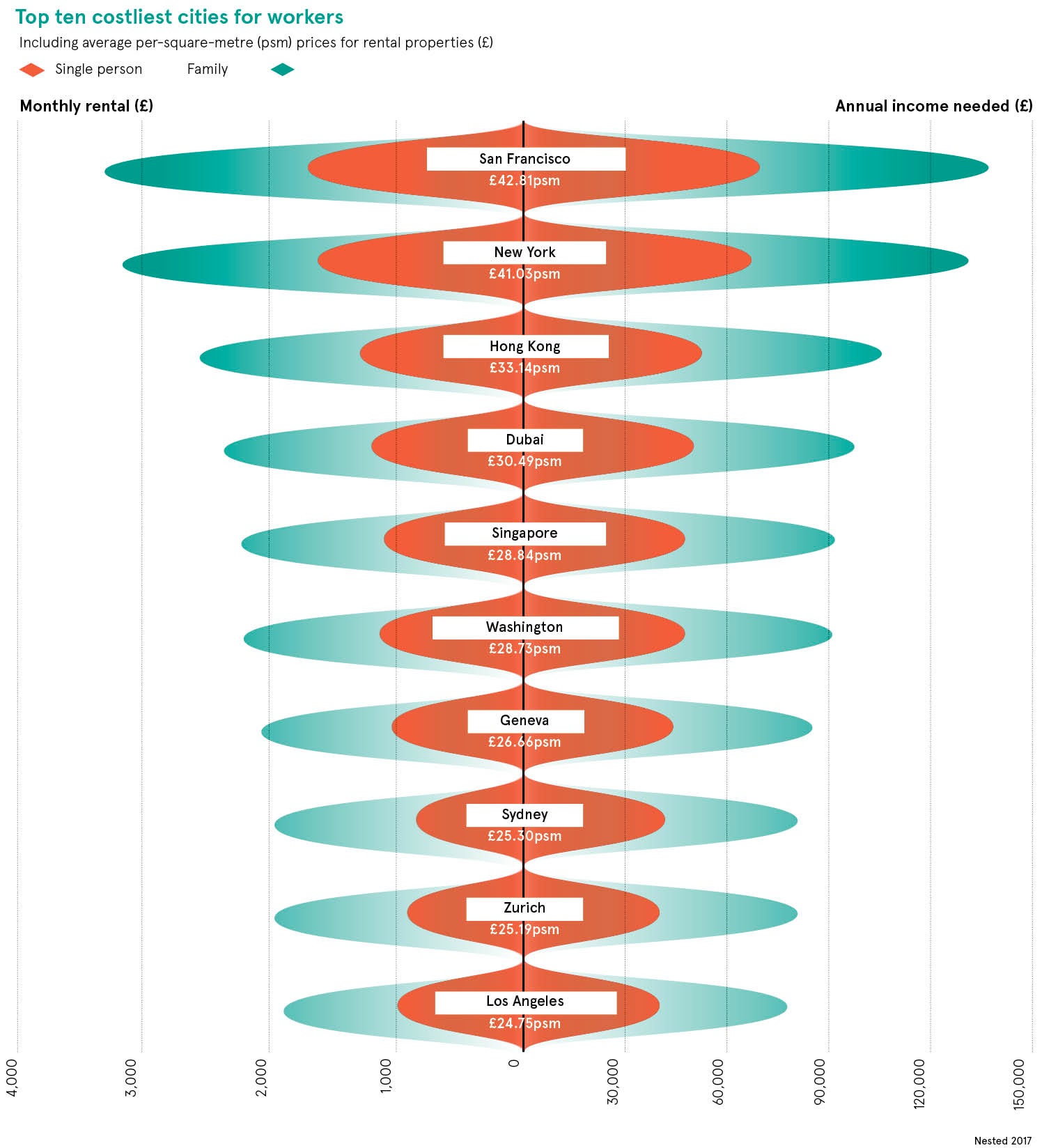

A dream job in the big city can come with complications. For many ambitious young graduates, the biggest headache attached to landing a role in London, Sydney or New York is finding somewhere affordable to live. If the lack of cheap housing in major cities has become a worry for the millennial workforce, it’s also a significant recruitment problem for companies around the world.

Leading employers have realised the most lucrative benefit they can offer is help meeting housing costs, whether it be loans, subsidies or mortgage deals

Housing pressures have forced the corporate world to rethink the perks used to entice top talent. With bicycle racks, free gym membership and paid volunteering leave now commonplace sweeteners, some leading employers have realised the most lucrative benefit they can offer is help meeting housing costs, whether it be loans, subsidies or mortgage deals.

Facebook and Google have even drawn up plans to construct housing for tech workers struggling with prices in the San Francisco Bay Area, a return to the days when philanthropic industrialists created company towns and model villages with the aim of improving the lives of labourers.

London prices becoming a barrier to entry-level recruitment

So what exactly can businesses do to ease the housing problems experienced by urban workers worldwide? Could the scale of the crisis push large employers into buying or building homes for staff?

In London the shortage of affordable homes is making business leaders anxious. Some 66 per cent of companies in the city said housing costs and availability were having a negative impact on entry-level recruitment, according to a recent CBI/CBRE survey.

Dozens of leading employers have agreed to a pledge drawn up by the Mayor of London to provide some form of housing help. Professional service giant KPMG has arranged preferential mortgage rates for employees with leading banks. Its rival Deloitte, meanwhile, has set up around 150 new recruits in East Village apartments under terms negotiated by the company, including free superfast broadband, free rent for two weeks, no deposit and no registration fees.

James Ferguson, partner at Deloitte UK, thinks big firms could go further in the years ahead. “In future, employers may want to look at longer-term leases or even decide to buy and own property that could be made available to employees,” he says.

Global organisations making strides in employee housing

If UK bosses are gently interceding in the housing market, companies elsewhere are making stronger interventions. Productivity is a motivating factor. A ready supply of accommodation close to the factory or office means employees aren’t drained or distracted by long commutes.

Swedish chain IKEA is constructing a 36-unit apartment building for its employees close to its store in the Icelandic capital Reykjavik, offering employees lower-than-average rents and an easy walk to work. In the Danish town of Billund, toy giant LEGO is constructing small apartments for workers as part of its revamped global headquarters, a place where the company hopes staff can “socialise both during and outside working hours”.

The company housing complex is already a familiar part of the landscape in South Korea. Electronics giant Samsung maintains a cluster of high-rise apartment buildings for its workers in the capital Seoul and Suwon.

In China, some major tech companies and multinationals are now providing housing assistance to employees faced with rising costs in urban hotspots. Shenzhen-based internet conglomerate Tencent has offered interest-free loans to help employees buy property in the city. Ecommerce company Alibaba has opted to build 380 apartments next to its headquarters in Hangzhou. And Starbucks now offers its full-time workers in China subsidies to cover part of their rent.

Lengthy commutes and high rent damage employee engagement

“There has been a lot of discussion about young workers who say they want to move back to their hometowns because the cost of housing in big cities is too much for them,” says Joe Zhou, head of China research at property group JLL. “But at the moment offering housing or subsidies for housing is not something many companies can afford to do.”

Despite the expense, top US companies hope housing subsidies can help them hold on to talent. Evolv research shows people with a commute of five miles or less stay in jobs 20 per cent longer. The need to retain valued workers explains why some employers are incentivising a move closer to the office.

Audiobook company Audible, for example, has encouraged staff to relocate from the hippest neighbourhoods of New York to its base in Newark by offering a $250 rent subsidy. Audible also introduced a housing lottery scheme and the 20 lucky winners had a year’s rent in Newark paid for by the company.

Silicon Valley housing could mean work-life balance takes a hit

Much more grandiose plans can be found in Silicon Valley. The supply of homes in the San Francisco Bay Area, home to Facebook, Google and Apple, has come nowhere near meeting the intense demand brought on by the tech boom. Property prices have skyrocketed and rental accommodation is hard to find.

In a bid to ease the pressure, Facebook has come up with a plan to build 1,500 homes next door to its Menlo Park headquarters. Not to be outdone, Google and its partners have won approval for almost 10,000 new homes around its base in Mountain View.

Silicon Valley may have a singular culture as a place where the work-life balance has not been cherished, and coders take their naps, meals and haircuts on campus. Outside the confines of the Bay Area, it’s unclear how many people would actually want to live in settlements shaped and dominated by their employer. There’s also scepticism about the long-term planning housebuilding requires from whoever commissions it.

“Corporate culture has changed so dramatically and the whole idea of a job for life has gone,” says Allison Arieff, editorial director at the urban policy think tank SPUR. “I’m not sure the company town where all workers are housed together is coming back anytime soon.”

No doubt most companies will continue to leave the creation of new communities to the politicians, planners and architects. But ignoring workers’ housing struggles is no longer viable. Businesses truly interested in their employees will have to be interested in whether they have a decent place to live.

London prices becoming a barrier to entry-level recruitment