“I was alone, isolated, lost in the midst of the immense sea, and I did not see anything on the horizon.” No, not Brexit punditry, but the words of intrepid French aviator Louis Bleriot upon landing his aircraft in Dover on July 25, 1909, following a foggy 37-minute flight from Calais.

The significance of this? It was the first time the English Channel had been crossed by an aeroplane and, beyond ticking a box in the evolutionary timeline of European aviation, Bleriot’s pioneering achievement signified a catalytic moment, a genesis of aerial connectivity between the UK and mainland Europe.

That airborne linkage has morphed into the prime conduit for intra-European trade and tourism. “The UK is geographically very well placed, with only 11 per cent of European airspace, but 25 per cent of its traffic and with some 80 per cent of transatlantic traffic using our airspace to access Europe,” says Dave Curtis, head of future air traffic management and policy at NATS, the UK’s main air traffic control provider.

We are Europe’s transatlantic gateway and we need to build on that to consolidate our position as one of the leading global economic hubs

He points out: “We are Europe’s transatlantic gateway and we need to build on that to consolidate our position as one of the leading global economic hubs.” Moreover, a study published in April by the International Air Transport Association corroborates that European air connectivity supports 11.7 million European jobs and $860 billion of European GDP.

A history of collaboration

Not only is it a key protagonist in Europe’s airspace infrastructure, the UK also plays a dominant role in European aeronautical design, innovation, research and manufacturing. Since joining the European Union, or the European Economic Community as it was in 1973, the UK’s aviation expertise and aero-industrial resources have become deeply intertwined with their continental counterparts.

Initially, this was through the design, development, construction and service-entry of the Anglo-French supersonic airliner Concorde and subsequently through deeper integration with mainland Europe’s aviation ecosystem, particularly via the Airbus Consortium; the UK arm builds the wings for every Airbus airliner.

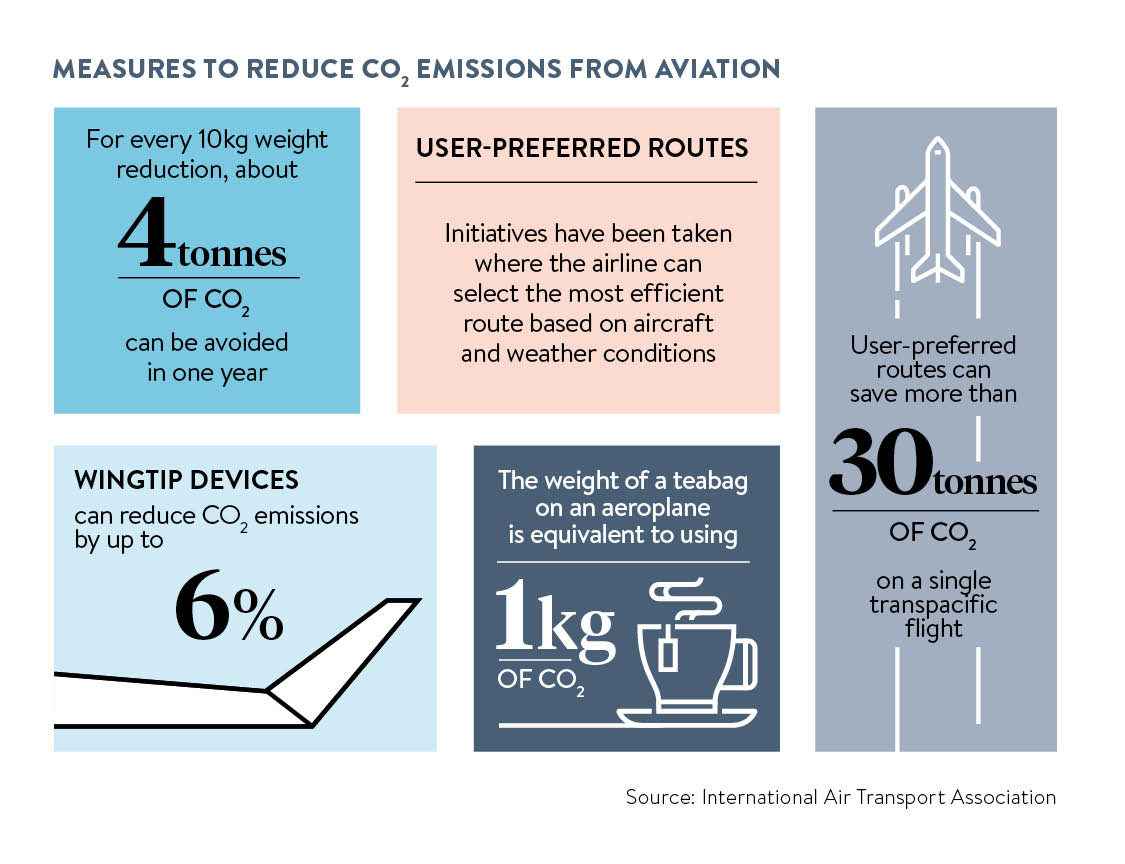

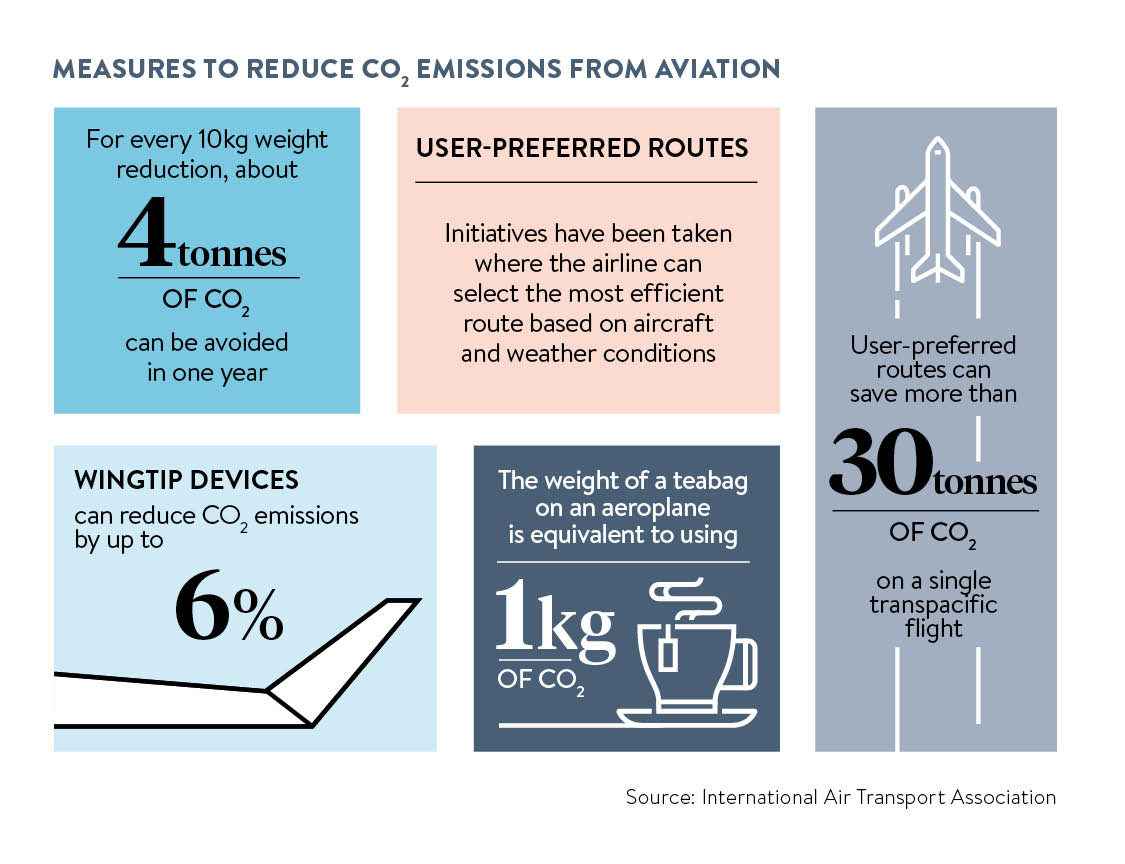

As air transport infrastructure and manufacturing have flourished through European collaborations, burgeoning passenger traffic, which is set to double by the early-2030s, continues to raise concerns about aviation’s environmental impact.

In unison with its European colleagues, the UK has been working to address aircraft noise and emissions as it tackles fuel efficiency and capacity concerns, using smarter air traffic control

innovations and by introducing greener aircraft. And it’s an effort supported by the airlines that strive to facilitate capacity growth while upgrading to environmentally friendly planes.

A case in point is the recent $4.4-billion order by Virgin Atlantic for 12 Airbus A350-1000 aircraft. “Sustainable growth and meeting our carbon targets is incredibly important to us and the aircraft’s environmental credentials were a genuine factor in our selection,” according to the airline’s president Sir Richard Branson.

The planes, powered by Rolls-Royce Trent XWB engines, are designed to be 30 per cent more fuel and carbon efficient than the ones they replace, while reducing the airline’s noise footprint at airports by more than half.

Clean Sky

Underpinning European aviation’s quest for greener aeronautics is a €4-billion public-private partnership called Clean Sky, funded jointly by the European Commission and Europe’s main aerospace entities. Airbus and Rolls-Royce are major players in this collaboration, which focuses on developing ecological technologies for tomorrow’s aircraft, and enabling deeper aero-industry engagement between the UK and Europe.

Airbus is involved in multiple Clean Sky projects, including a new focus on advanced engine and aircraft configurations to explore and validate the integration of fuel-efficient propulsion concepts for next-generation short and medium-range aircraft, as well as new ways to integrate aircraft cabins, systems and structures to bring weight reductions which translate into fuel savings.

An unanticipated wall of fog between the UK and Europe has suddenly obscured the flight plan

“By taking part in the EU’s Clean Sky initiative, we will not only reinforce Europe’s industrial leadership and future competiveness, we will also help enhance the sustainability and efficiency of commercial aviation,” says Axel Krein, head of research and technology at Airbus.

Rolls-Royce, meanwhile, is engaged in developing and testing the next generations of engine technologies, such as Advance, which will reach market in five years, reducing emissions by 20 per cent, and UltraFan, scheduled for service-entry in the mid-2020s with 25 per cent less emissions. Increasingly, the company is looking to use additive layer manufacturing (3D printing) to achieve what it says is a “30 per cent like for like reduction in manufacturing lead time”.

Significantly, the UK has 69 organisations in the Clean Sky ecosystem with participation in 145 technology programmes. But as with Bleriot’s Channel crossing, an unanticipated wall of fog between the UK and Europe has suddenly obscured the flight plan, following the outcome of the EU referendum. Could Brexit affect the UK’s continuing involvement in Europe’s collaborative efforts for a greener skyscape?

“At Farnborough [International Airshow], Clean Sky was an active exhibitor, bringing some 20 innovative pieces of hardware representing different technology platforms, including engines, wings, systems and eco-design within our research programme,” says Eric Dautriat, executive director of Clean Sky.

Accentuating the UK’s contribution, he continues: “We celebrated, in particular, the participation of the University of Nottingham, which has been an important player from the beginning and has recently won several large-scale research topics.”

With regard to the UK’s future relationship in EU aerospace programmes, green and otherwise, Mr Dautriat declares: “EU law continues to apply to the full to the UK and in the UK, until it is no longer a member.” For the moment, at least, as far as European collaboration on creating eco-friendly solutions for air travel goes, it seems it’s business as usual.

CASE STUDY: NOTTINGHAM UNIVERSITY

A new approach to runways is paying ecological dividends. Reducing noise and fuel-burn as planes taxi from the terminal gate to the runway threshold are major environmental objectives at airports.

A new approach to runways is paying ecological dividends. Reducing noise and fuel-burn as planes taxi from the terminal gate to the runway threshold are major environmental objectives at airports.

Aircraft usually use thrust from their jet engines to push themselves along the taxiways in readiness for departure – a wasteful, noisy process, especially when planes get stuck in a queue for take-off. Multiply that unwanted environmental impact by more than 100,000 global daily flights and the scale of the challenge becomes all too apparent.

One of the UK’s leading aeronautical research centres, the University of Nottingham, has developed a solution in partnership with Germany’s DLR (national aeronautics and space research centre), and France’s Safran Landing Systems and Adetel Group.

Working together with Clean Sky funding on a programme called the Green Taxiing Demonstrator, designed for medium-sized airliners such as the Airbus A320, their solution is to integrate an electric motor into the aircraft’s landing gear, enabling taxiing without reliance on the aircraft’s engines.

A logical concept, but implementation requires elaborate technologies, after all the A320 weighs 78

tonnes. The benefits? Less fuel-burn means less carbon and nitrous oxide emissions, and quieter airports too. On a two-hour flight, fuel consumption could be reduced by 5 per cent, less engine use would reduce maintenance costs and expensive carbon brakes would no longer be required.

Now the tricky part: the system requires revolutionary new motor technology to move that kind of weight, but Nottingham University and its collaborators have come up with a peak torque density electrical motor, reaching values of 42Nm/kg and 184kNm/m³ – in plain English it’s a paradigm shift in electrical motor science.

Developed to technology readiness level 5 – industry jargon meaning prototype testing has been completed under realistic conditions, meeting environmental targets – Safran is now evaluating production options with a view to implementation into aircraft in the near future.

Nottingham University exhibited the Green Taxiing system at Farnborough Airshow and simultaneously announced it had secured £9.5 million of Clean Sky funding to develop further breakthrough aerospace technologies for leading European manufacturers designing the next generation of aircraft.

And Brexit? “There is a continued, strong appetite from industry and Europe for us to remain strongly engaged after Brexit. At present, nothing has changed,” says Professor Hervé Morvan, director of the University of Nottingham’s Institute for Aerospace Technology. “We encourage industry and academia globally to continue to see Nottingham as a collaborator of choice because of our strong research, training pedigree and innovation capabilities in aerospace.”

A history of collaboration