For centuries banks have enjoyed an almost exalted status. Governments and regulators have allowed them to dominate much of the financial services landscape, including current accounts, deposit accounts, loans, payments, debit cards, credit cards, mortgages, pensions and insurance, on condition they keep money and credit flowing around the economy.

Barriers to entry have been so high and customer inertia so strong that the banks have been able to thrive despite offering what has often been a poor and anachronistic service.

Much of this will change on January 13, 2018 when the European Union’s second payment services directive (PSD2) takes effect. The legislation aims to give consumers better protection when they make online payments, to promote the development of innovative online and mobile payment systems, and to make cross-border European payment services safer.

The directive will effectively prise open the payments market, while compelling banks to release their tightly held customer data to third-party companies, which will be lightly regulated as long as they can prove their data defences are robust and that the customer has given their consent.

The banks’ reaction

Initially the legislative change, which was approved by the European Parliament in October 2015 and will apply to Britain despite Brexit, provoked wailing and gnashing of teeth in the executive suites of most of Europe’s banks. Bankers feared their institutions would be squeezed out of the market by Chinese apps such as Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu, cutting-edge businesses which have the advantage of having grown up in the digital age and have already managed to integrate social, commercial and financial into a single app, as well as Silicon Valley players, notably Apple, Google and Facebook.

Chris Skinner, chief executive of Balatro and author of Digital Bank: Strategies to Launch or Become a Digital Bank, says banks have been lobbying in Brussels and Washington to get the requirement to hand over their customer data blocked or watered down. In the United States, where legislation along similar lines to the EU directive is mooted, banks have been more successful persuading regulators and politicians that it is in nobody’s interest for them to lose control of their data.

But others argue banks have latterly been more accepting of PSD2 and “open banking”, and anyway the tech giants are less eager to become fully fledged banks than they were a couple of years ago as a result of the regulatory headaches this would entail and reduced profitability of the banking sector.

Jonathan Turner, payments leader at PwC, says the mood has shifted from fear of being disintermediated out of existence to enthusiasm for the opportunities ahead. “Banks now universally see it as a strategic opportunity, and are being very proactive and ambitious about it,” he says.

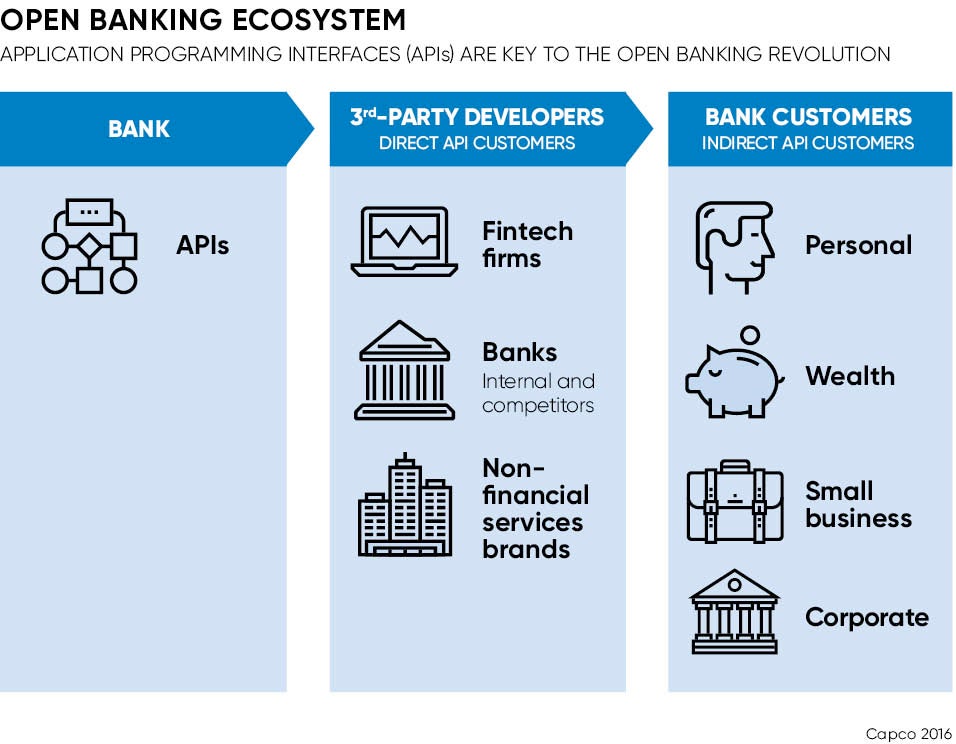

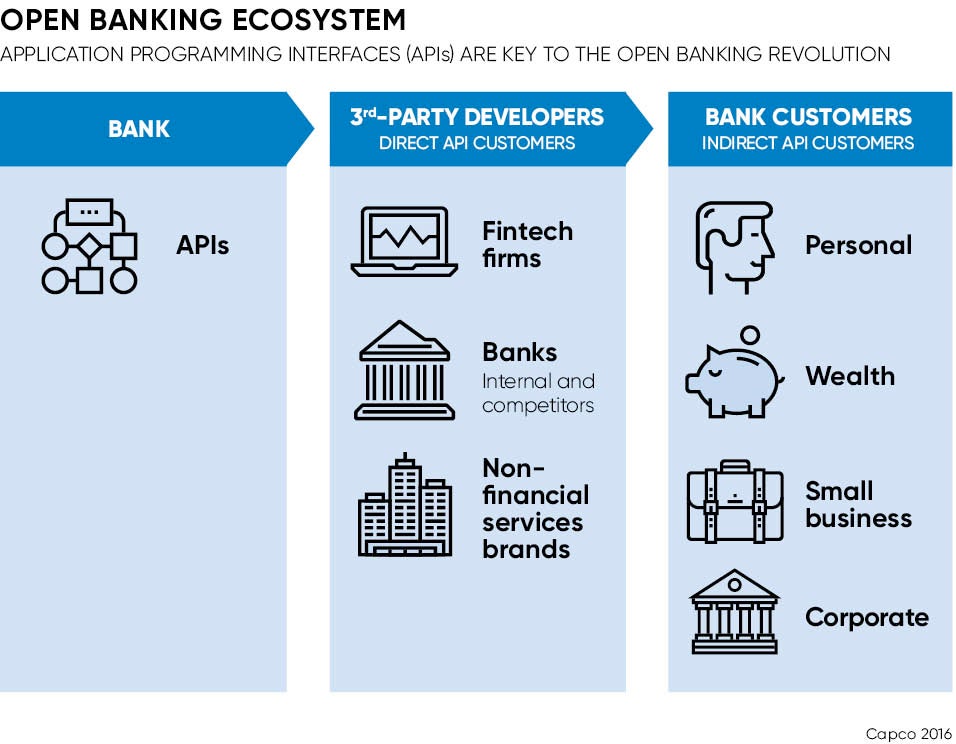

Application programming interfaces (APIs) are pivotal to banking’s brave new world. Danny Healy, financial technology evangelist at MuleSoft, describes these as the ”digital glue” that will enable incumbent banks and new payments players to interact seamlessly, share data, and offer more apposite and timely financial products to consumers.

“APIs allow banks and their partners to track a far greater portion of customers’ lives and day-to-day behaviour than currently,” says Mr Healy. “They help banks get closer to their customers and deal with many more niches than they’re capable of doing today.”

Under an “aggregator” or “marketplace” strategy, banks will in future offer a “catalogue” of APIs, he says, drawing parallels with the way apps are presented on a smartphone. “If they can make their APIs readily understandable and easy for developers to consume in a self-service, independent way, then they’ll attract those third parties,” he adds.

The role of startups

Acknowledging they are out of their depth in the new digital environment, many banks have been casting the net wide and getting into bed with large numbers of financial technology startups.

Mr Skinner says: “A common strategy is to support startups to ‘play’ with their business and, where those companies are successful, to take ownership of those companies.”

Recent tie-ups have included HSBC’s partnership with six-year-old Danish company Tradeshift, described as “a social market for invoices”. Spanish bank BBVA, widely regarded as being way ahead of the curve in digital banking, is a majority shareholder in UK-based digital startup Atom Bank. The Madrid-based bank has also acquired Holvi, a Finnish API-based fintech innovator, which specialises in small business payments, and US-based Simple, an established retail digital bank that uses APIs to analyse customers’ monthly expenses and assist them in managing their money to meet defined objectives.

Banks now universally see it as a strategic opportunity, and are being very proactive and ambitious about it

Unless banks radically modernise their systems, they risk being left behind and becoming little more than “dumb pipes” in the new environment, providing the back-office financial plumbing through which consumer-facing brands such as Simple channel their products and services to market.

PwC’s Mr Turner says: “If a bank decides to do nothing with PSD2, the danger is they slip into becoming a utility, in which case the brand would start to drift away and the added value the consumer sees starts to evaporate.”

According to Mr Skinner, silo-like structures, warring internal fiefdoms and the lack of technologists on their boards are also holding banks back. He says some British banks, including RBS, have tried and failed to move towards “enterprise data architecture”.

“If you don’t have enterprise data architecture, you will never be able to exploit artificial intelligence or leverage analytics for consumer relationships,” he says. Ultimately, banks without enterprise data architecture will be so weakened they are likely to fail or succumb to takeover, Mr Skinner warns.

Ewan Fleming, financial services practice leader at Grant Thornton, says the death of the current account, which he predicts will be in a decade, is another issue for incumbent players.

“Current accounts have been the hub and consolidating product for banks over the past many decades, so when they go we will see an accelerated fragmentation, with better informed and more price-conscious customers becoming much more willing to spread their business around. This fragmentation is going to destroy the economics of the way big banks run their businesses,” he says.

Branch networks will become even smaller than their current pared-back form and banks will derive less revenue from retail payments. Bob Graham, senior vice president at VirtusaPolaris, estimates banks will lose between 8 and 10 per cent of retail payment revenues to new payment competitors. In Europe that implies a loss of some $13 billion of revenues across the banking sector.

“Banks have a strong presence in terms of millions of customers, billions of capital and centuries of history, but that could be wiped out in ten years if they don’t adapt to opening up their capabilities for others to play with them,” says Mr Skinner. “The survivors will be the banks that can curate best-of-breed services to their customers.”