One of the fastest expanding financial services sectors globally is Islamic finance, which has consistently shown growth rates of around 10 to 12 per cent annually over the last two decades and has assets of around £2.5 trillion. Outside the Middle East and Asia, the UK is the leading hub for the sector and was the first non-Muslim majority country to issue a sovereign Islamic bond, known as sukuk, of £200 million in 2014.

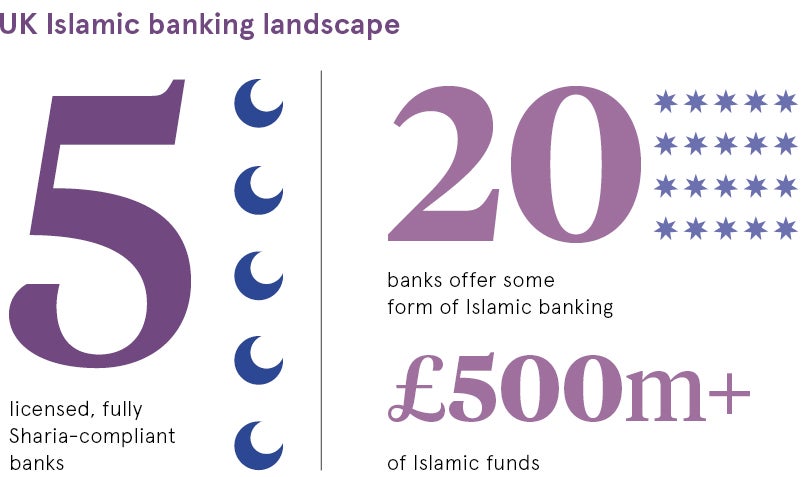

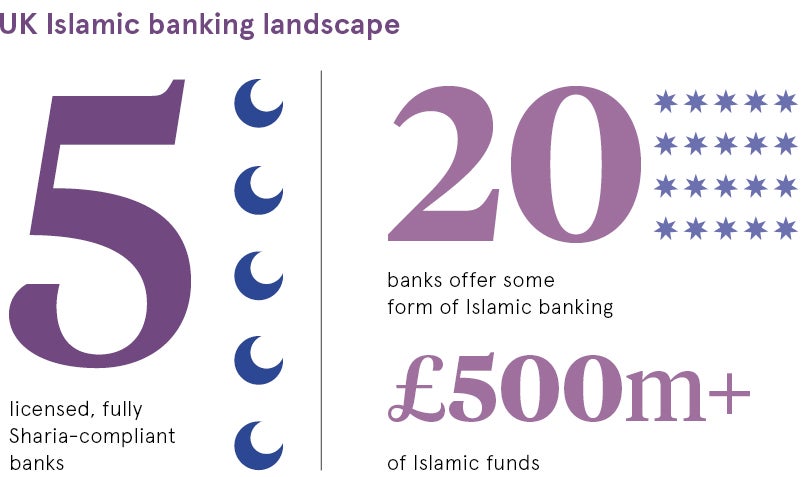

There are five licensed, fully Sharia-compliant banks in the UK, with more than 20 other banks offering some form of Islamic banking, and more than £500 million of Islamic funds, hosting the issue of 65 sukuk, worth £35 billion.

The UK, especially post-Brexit, may become an even more attractive destination for Islamic finance globally. As Dr Bandar M.H. Hajjar, president of the Saudi Arabia-based Islamic Development Bank, said recently at a sukuk conference held at the London Stock Exchange: “You have the necessary financial, regulatory and legal experts to develop the UK market into a thriving global hub for Islamic finance.”

However, even among the UK Muslim community, Islamic finance remains relatively unknown and misunderstood. The modern era of Islamic finance began in the 1970s in parallel streams centred on the Gulf States and Malaysia. Growth has mainly been in the development of Islamic banking services, the issuance of sukuk and provision of Islamic insurance, known as takaful.

Mohammed Amin, former partner and head of Islamic finance for PwC and currently an Islamic finance consultant, explains: “Islamic finance in reality fulfils the same basic function as conventional finance. It simply obeys a set of rules that are outlined in the Koran.” These rules include the exclusion of investment in the manufacture of arms, production and sale of pork, alcohol and tobacco, prohibition of speculation, which includes futures, options and spread-betting, and making money from interest.

Islamic banks are funded by non-interest bearing current accounts as well as profit-sharing investment accounts where investors receive a return that is determined by the profitability of the bank or the pool of assets financed by these accounts. Banks do not engage in lending, but in sales, lease, profit-and-loss-sharing financing and fee-based services. In many ways the prohibitions of Islamic finance are similar to those of conventional ethical or socially responsible investment companies.

Majid Dawood, chief executive of Yasaar Capital, the first Islamic finance advisory company set up in the UK, says: “The majority of Muslims are unaware or unclear what Islamic finance actually means. Islamic finance institutions aren’t run on a charitable or non-profit basis, they are commercial organisations in the same way that conventional banks are.”

Mr Dawood believes there is great development potential for Islamic finance in the UK, both in the sukuk and retail markets. Earlier this year, Al Rayan Bank, the UK’s leading Sharia-compliant retail bank, became the first financial institution outside the Muslim world to issue a corporate sukuk, raising £250 million in residential mortgage-backed securities.

Sultan Choudhury, the bank’s chief executive, thinks Islamic finance could have an even-greater influence in the UK, especially in the area of infrastructure development and regeneration.

There is potential for the UK to receive foreign direct investment for infrastructure from the Islamic finance market

“I know that in the last few years the government presented a number of UK development projects to Islamic finance and GCC [Gulf Co-operation Council] investors,” he says. “I think there is potential for the UK to receive FDI [foreign direct investment] for infrastructure from the Islamic finance market. But the government needs to understand how to structure these projects to make them attractive to Islamic finance investors and come up with more innovative ways to put these opportunities together.”

The global Islamic finance market could also help develop other parts of the UK’s economy. Harris Irfan, managing director of Cordoba Capital, argues that Islamic finance could be used to boost UK small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by creating a Sharia-compliant SME fund so that FDI from the Gulf and Southeast Asia would help plug the funding gap in the heart of the UK economy.

These are interesting times for Islamic finance as a picture forms around the potential effects of the UK leaving the European Union. As with most aspects of Brexit, at this stage it is impossible to predict exactly what those effects might be. However, there are indications that an exit from the EU may not have a detrimental impact on Sharia-compliant finance. Indeed, it could well create an environment that benefits it.

Wayne Evans, senior adviser for TheCityUK, a financial services lobbying group, believes the UK’s departure from the EU will have no bearing on its ability to realise its potential in Islamic finance. “Brexit is essentially a European issue. It should not affect the UK’s Islamic finance industry’s relationship with the rest of the world,” he says. “If anything, it will make London even more determined to build on its international business, so there should be increased opportunity to attract Islamic investment.”

Tariq al-Rifai, chief executive of the Quorum Centre for Strategic Studies, a think-tank specialising in Middle Eastern affairs, agrees. He points out that the UK has historically been a haven for Middle East investment and, more recently, Islamic investment. “A vote on leaving the EU will not change this,” says Mr al-Rifai. “In fact, at Quorum Centre, we believe that the UK would attract more foreign investment being outside the EU; having the flexibility to negotiate its own free trade deals with countries in the Middle East is just one example of how the UK would benefit.

“Brexit or no Brexit, Middle East investors will continue to invest in the UK and will continue to prefer Islamic finance over conventional finance for UK investments.”