What happens when Silicon Valley thinking comes to the world of money? One answer is Square, Inc.

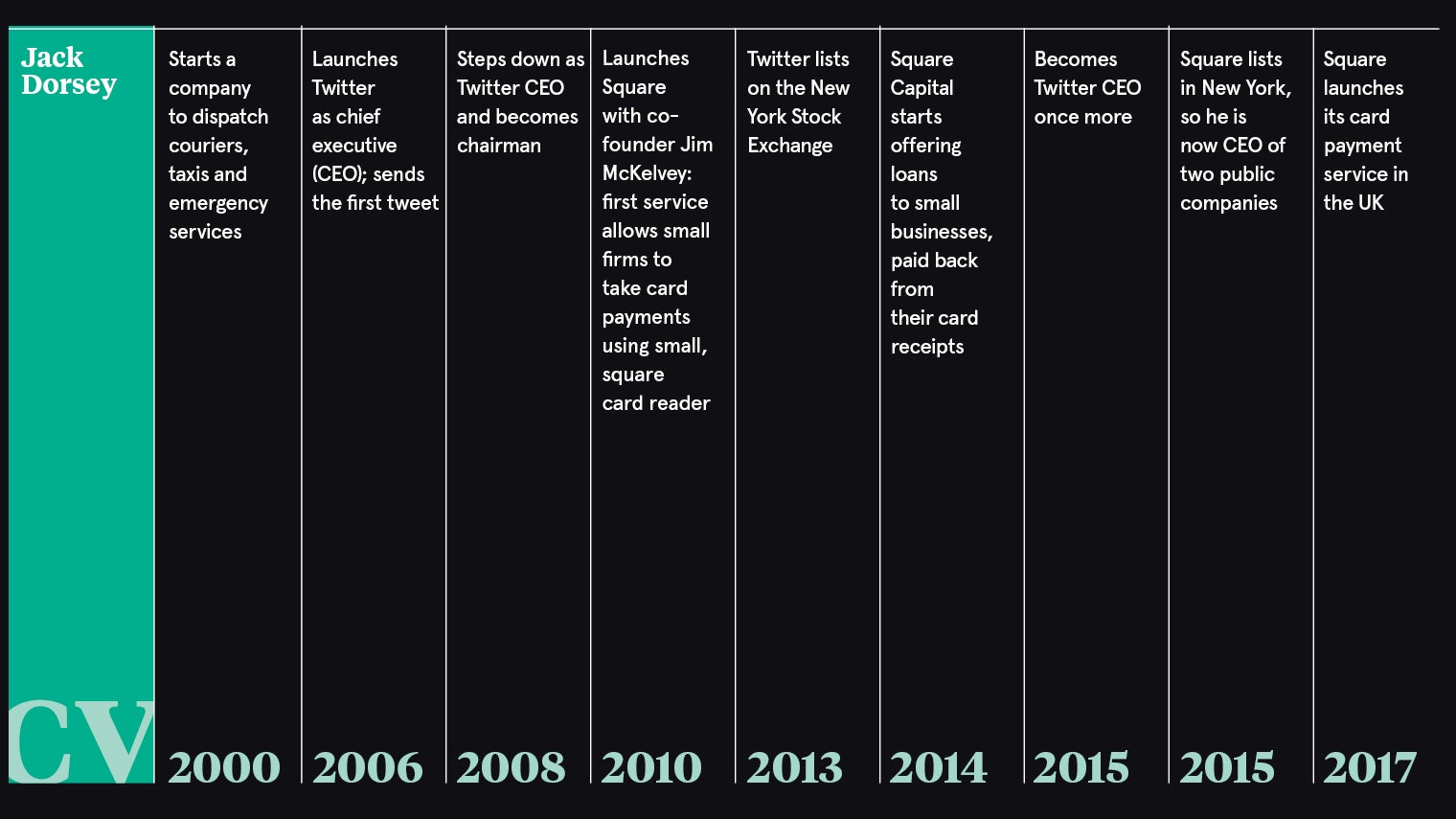

Co-founded by Jack Dorsey, also a founder and chief executive of Twitter, the nine-year-old company offering financial services to both companies and individuals has a market value of $23 billion, almost half the value of 328-year-old Barclays.

Yet in an interview during a recent visit to London, Square’s chief executive Mr Dorsey doesn’t sound like a fintech boss. While many tech firms brag about trying to destroy the banks, he says: “That’s not our intention. We think the banking system works – it’s just not accessible.” And while many other US tech firms, in particular, are dismissive of regulation, Mr Dorsey declares that “regulation is really important” in finance.

We think the banking system works – it’s just not accessible

And the phrase “disruptive innovation”, so beloved of fintech startups, doesn’t seem to be in his vocabulary. His favourite word, perhaps, is “customer” and a relentless customer-centric approach is why Square and other firms with the same mindset represent such a threat to established financial services.

All tech companies need a founder’s tale and Square’s appropriately enough is about focusing on the customer. Jim McKelvey, a friend and former boss, had a business making artistic glass sculptures-come-water fountains and in 2009 lost a $2,000 sale because he couldn’t take credit cards.

The two of them looked at the merchant side of the credit card business and asked basic questions about why it was so hard for a small business to accept cards. Mr Dorsey admits their knowledge of the credit card business was negligible, but it is clear that he regards this, in the circumstances, as an advantage.

In only a month, the two engineers developed the concept of a simple gadget that plugs into a smartphone and allows a small trader to take cards, using the florist across the street from Mr Dorsey’s apartment as a one-person focus group.

He says only 30 to 40 per cent of small traders in the United States who ask to process cards get accepted by banks. For Square, he says, the figure is 99 per cent, but the company watches customers closely and if they don’t like the transactions being processed the service can be suspended.

However, Square wouldn’t have reached $23 billion in market value without two further insights. First was that the square gadget was just the start of a business serving people underserved by traditional finance. “We don’t want to replace a bank; we don’t want to replace a financial institution,” he says. “We want to make what they have, which works, more accessible.”

The second was that a relationship that starts with the card reader could get much deeper, powered by the data collected. The power of data in financial services is well understood in the US. A firm named Credit Karma, for instance, offers free credit checks and then uses that data to tout extra services, generating revenues of $500 million in 2016, according to its latest figures.

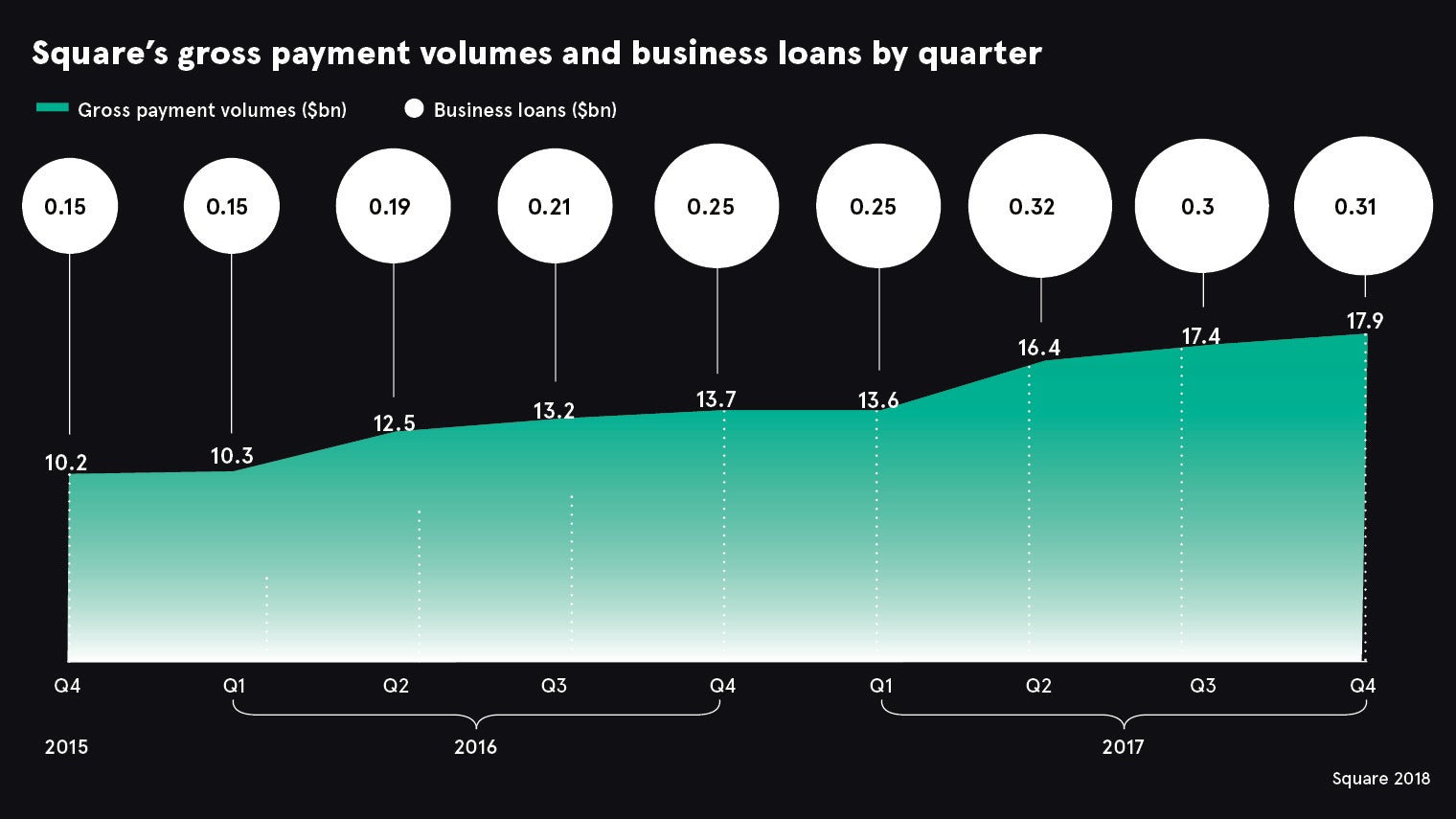

Although in many ways the UK is ahead of the US on payments – Americans were swiping and signing long after Europe was using chip-and-PIN – but on using data it lags. Square’s operations in the US show how data can be put to work. In 2014 the firm launched Square Capital, which lends to Square customers. After analysing card receipts and other data, an algorithm will send an email offering an entrepreneur a modest loan, instantly. The customer can click a box and have funds the next day, to be repaid from the card receipts.

This may sound very much like banking business and indeed Square uses a banking partner to offer this service. However, with the typical loan around $6,000, the amounts are less than those considered viable for a big bank, with its overheads, to make a profit.

Mr Dorsey says this isn’t taking a bank’s business because a small-business owner needing this kind of loan will not usually get it from a bank. “What we’re replacing is people having to go to their friends and family to ask for that money. And that’s a huge market,” he says.

The eventual aim is to bring all products to all markets. However, in the UK, Square’s only market in Europe, it currently offers its core card service and, just launched, an instant-deposit add-on which allows small business to get their card payments in minutes instead of, usually, the next day.

Its portfolio is much wider in the US. There Square has also launched Square Cash, which started out as an app that allows peer-to-peer payments between individuals, with the classic example being friends splitting a restaurant bill after a night out, in competition with PayPal’s Venmo. Square Cash customers can now get a payments card and pay in their salary. Mr Dorsey says some users find they don’t need a conventional bank account.

As he notes: “If you look at any bank’s website and look at the services they offer, and look at our website, we’re ticking a lot of the boxes.”

Square is not a bank so it needs to partner with banks to offer its services. “Partnership with a bank was the fastest way we could move and also the best way we could move,” he says. It has applied for a banking licence in the US because it brings “operational efficiencies” rather than from a desire to do conventional banking business. Yet it’s clear that Square and other tech-focused outfits are increasingly doing jobs that were previously moneymakers for banks and other traditional financial firms such as Western Union.

We don’t need to become a bank to save a trip to the bank

Snapchat, for instance, makes it very easy for a user who has entered their card details to flick some cash to a friend. Google’s Gmail, although few have noticed it, allows users to send funds as easily as sending an attachment.

Helped by their quick decision-making and flexible technology platforms, tech-based firms have a natural tendency to expand their services that most banks would envy. In the case of Square, although it started with small businesses that struggled to get banks’ attention, their payments platform is now attracting larger businesses.

In 2017 Square moved $65.3 billion of payments, up 31 per cent from 2016, with one of the biggest increases from accounts with annual payments more than $500,000, the sort of firm the average high street bank would very much welcome as a customer.

Some of these firms were using Square’s payments infrastructure as a platform, connecting their system into Square’s rather than using the reader or the other packaged services.

“Platform” is one of the biggest tech buzzwords as many entrepreneurs dream of emulating Airbnb or Amazon Marketplace in providing a critical middle role in transactions, taking a percentage cut along the way. But Mr Dorsey’s view is that the platform concept is only useful if it helps solve a customer’s problem.

“I think less about how we define these things versus what problems we’re solving,” he says. “Is a platform mindset going to be the best way to solve a seller’s need to grow their business? If the answer is ‘yes’, we do that.”

One of Mr Dorsey’s more unusual metrics is how many trips to a bank he has saved his customers. He checks them off. Downloading Square Cash instead of opening a bank account – that’s a trip saved. Getting a quick loan from Square Capital – that’s another trip saved. He says: “We don’t need to become a bank to save a trip to the bank.”