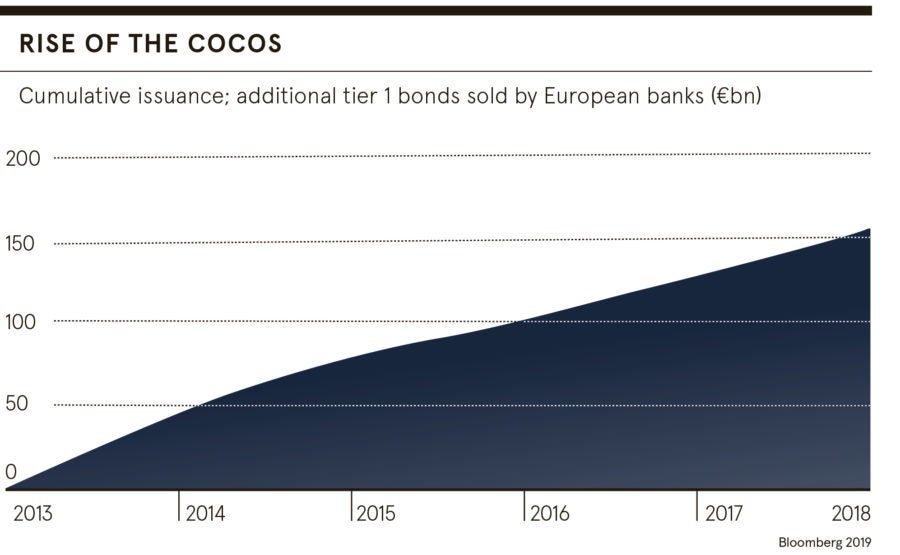

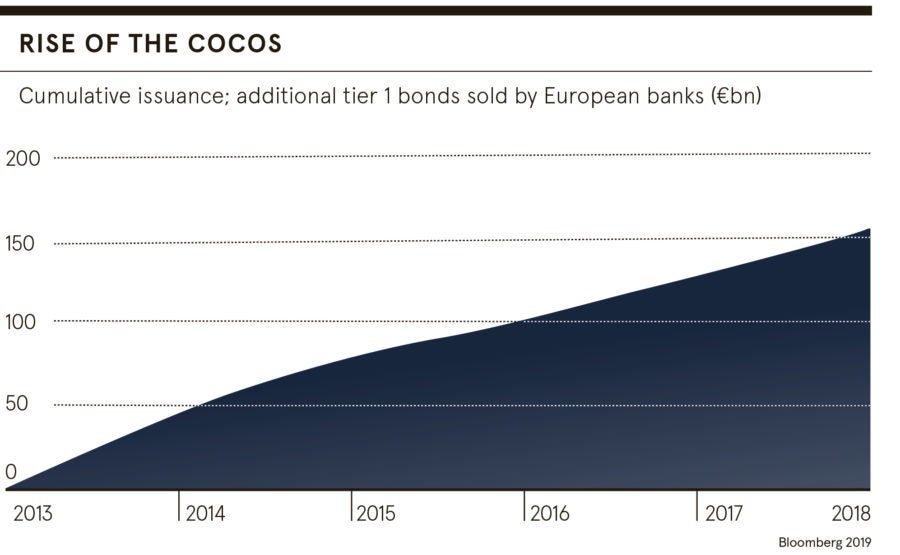

Contingent convertible bonds, or cocos, are bonds issued by banks and financial institutions that can be converted into equity in certain circumstances, for example when a bank’s regulatory capital falls below certain levels. Issuance has grown rapidly from 2014 as banks sought to meet higher Basel III capital requirements. They have been unavailable to ordinary UK retail investors since 2014, but many in the market argue the ban should now be lifted.

In October 2014, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) introduced a set of intervention rules, which became permanent in 2015, that restricted the retail distribution of coco bonds to ordinary retail investors but gave certain exemptions to wealthier and more sophisticated investors.

In explaining the move, Christopher Woolard, then-FCA director of policy, risk and research, acknowledged investors might be tempted as coco bonds offered high headline returns in a low interest rate environment. “However, they are complex and can be highly risky. The FCA has used its new powers to ensure that coco bonds are not inappropriately made available to the mass retail market while still allowing access for experienced investors,” he said.

The move was not without controversy and the FCA’s market consultation prior to making the rules permanent attracted a range of opposing views to the restriction on ordinary retail investors. The FCA pointed out how little experience the market had of how coco bonds operate.

Yet five years on since the move, no Sterling coco has defaulted and financial institutions have a full decade of experience in using contingent convertible securities. According to Credit Suisse, since 2010 Sterling cocos have returned 11.6 per cent per annum and over the past 12 months 12.2 per cent. More striking is that over the same period UK bank equity has lost 2.6 per cent per annum and lost 9 per cent over the past 12 months according to the FTSE All-share Bank Index.

Rezaah Ahmad, founder of digital bond market WiseAlpha, says: “When you consider that retail investors are limited to investing in the listed equity of banks but are blocked by a combination of regulator policy and the corporate bond market from investing in lower risk bank debt or coco securities issued by the same company, you naturally end up with perverse consumer outcomes, antithetical to the aims of regulators.”

Compared to the potential risks from other investments, such as equities, contracts for difference, peer-to-peer lending, equity crowdfunding or cryptocurrencies, is there now a case to revisit the restrictions placed on cocos and begin to open them up to individual investors?

Bank debt and assets

Denise Yung, portfolio manager in Lombard Odier Investment Management’s fixed income team, explains that because cocos are designed to absorb losses when an issuer’s capital ratio falls below a certain level, to fulfil this purpose they have a combination of equity and debt-like features, which does make them riskier than other debt instruments.

“The FCA restricted the retail distribution of cocos due to the riskiness and complexity of the instruments. The intention of the rules is understandable given the numerous mis-selling scandals in recent years and the attractive yields offered by coco bonds in an environment of low interest rates,” says Ms Yung.

“However, in our view, the perceived riskiness of the instruments is somewhat incongruous as cocos are arguably less risky than other securities that are available for retail distribution.”

Although there have been no problems for UK issuers since the launch of cocos, in 2017 Spanish bank Banco Popular Espanol had its additional tier 1 coco bonds fully written down after the European Central Bank determined it to be “failing or likely to fail” and it was sold overnight to Santander. Banco Popular’s equity and tier 2 debt, which ranked below and above its coco securities in the capital structure, was also wiped out, highlighting that while these are investments in highly regulated banks the risk of losing the entire investment remains.

Cost of capital

Nevertheless, cocos have become a very popular financing tool and issuance has continued, mostly recently in emerging markets such as those in Asia-Pacific, with some $675 billion in cocos outstanding worldwide by 2017. Most coco bonds paid a coupon of between 6 and 9 per cent at the start of 2019, with yields continuing to attract institutional investors in the ongoing low interest rate environment.

According to a European Parliament briefing, cocos are also attractive to issuers because they help them satisfy regulatory capital requirements. In addition, equity is more expensive than debt in the sense that borrowers face less risk than shareholders.

However, Bjorn Norrman, investment manager in the fixed income team at Kames Capital, warns that while it is true equity investments are seemingly riskier, given they sit at the bottom of the creditor hierarchy, bank equity is still a cleaner and easier-to-understand investment.

Their perceived riskiness is somewhat incongruous as cocos are arguably less risky than other securities

“Investing in cocos requires intimate knowledge of bank and/or insurance capital regulation and, more specifically, under what scenario a bond may be converted to equity or coupons cancelled. Without this understanding it is problematic to assess the risks or establish likely returns,” he explains.

“The high thresholds to investing in contingent capital are deliberate; regulators remain keen to protect direct investors from the allure of pure high coupons, not wanting that on their watch.”

Reviewing the regulatory response

Among the many anomalies and unintended consequences created during the financial crisis was the issue of bank subordinated debt instruments that qualified as capital and were supposed to be loss absorbing, but often proved not to be, according to Mr Norrman.

In response, global regulators have sought to rectify this situation by clarifying and co-ordinating how subordinated debt instruments should function in times of stress and, in particular, under what circumstances contingent capital bonds should be activated.

“This is now embedded in underlying bond documentation, but the assessment of whether a bank has reached the point of non-viability is also subject to regulatory discretion,” he says. “All in all this means that assessing the risk and complexity of contingent capital bonds can be nuanced.”

Concerns around the complexity of the instruments are more well founded given the variety of features and the relative infancy of the asset class compared with equity and other debt instruments, Ms Yung agrees. To make the instruments more accessible to retail investors, it would help to see a stabilisation in banking regulations and a standardisation of contractual terms to create a more homogeneous asset class, she argues.

“Concerns could also be addressed by educating investors to increase their knowledge and by applying an appropriateness test to check investors’ understanding of the instruments,” Ms Yung concludes.

Rezaah Ahmad, founder of WiseAlpha, says perhaps there is also something to learn from the retail market review that the FCA has been conducting in the peer-to-peer lending space. Over the past five years the FCA abstained from placing any restrictions on retail investment in peer-to-peer lending while it observed, learnt and implemented rules for the industry.

The extended FCA review of the P2P market allowed a natural testing period to occur, forming the basis for the FCA to conclude that it would be suitable to introduce an appropriateness test for retail investors coupled with a limit for retail customers new to the sector of 10 per cent of investable assets.

Christopher Woolard, the FCA’s executive director of strategy and competition, said the changes were about “enhancing protection for investors while allowing them to take up innovative investment opportunities. For P2P to continue to evolve sustainably, it is vital that investors receive the right level of protection.”

Would a similar approach towards the coco market help create the industry conditions necessary for mainstream retail market participation?

Bank debt and assets

Cost of capital

Reviewing the regulatory response