“In every investment call I have, people say: ‘Give me more green bonds,’” says Professor Sean Kidney, co-founder and CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative. “That makes me hopeful. Green bonds have grown up.”

His organisation is a not-for-profit body working to mobilise international capital for climate action. It works in more than 30 countries with partners including BlackRock, Allianz Global Investors and Credit Suisse, as well as advising several national governments.

The first ever green bond, designed specifically to raise money for environmental projects, was issued in 2007 by the EU’s European Investment Bank (EIB). Having grown steadily since then, this market is now valued at nearly £1.1tn.

“It’s no longer a small concern,” notes Kidney, who adds that there is still plenty of growth potential, given that the overall bond market is worth about £100tn.

Having served as an adviser to the United Nations’ secretary-general and a member of the People’s Bank of China’s task force on green finance, Kidney has been a key player in sustainable investment for more than a decade, winning accolades as a champion of climate finance. He’s currently a member of both the UK government’s green gilt advisory committee and the European Commission’s Platform on Sustainable Finance.

Kidney launched the Climate Bonds Initiative during the UN’s “depressing” COP15 climate conference at Copenhagen in 2009. The politics of that event were all wrong, he explains. China was largely ignored while those seeking change wasted their energy berating President Obama when the US Congress was actually blocking progress.

The truth is that the climate figures are not going our way

So what has changed over the intervening 12 years?

“We have established that, from an investor’s perspective, green bonds perform better,” Kidney says. “This is about risk management, tied to the fact that governments are starting to act.”

Initiatives tied to combating climate change are less likely to be affected by policy changes, he explains. This makes them a much lower-risk option for investors than they once were.

“If something is green, there isn’t much chance that someone would kick it over,” Kidney says. “There’s a lot of money around that needs to go somewhere at the moment. In essence, if you’ve got a fossil-fuel bond, it’s hard to get a good price. If you’ve got a green one, you’re going to get more investors and a better price.”

While the initial price of a green bond may be higher, investors know that they will also sell at higher prices. “Suddenly, every sustainability manager of an investment fund around the world has become popular. It’s an amazing situation: investors are doing better and issuers are doing better too – it’s booming.”

Governments that understand the need to act urgently on climate change have picked up on this and started introducing their own green bonds. When, for instance, the UK government issued its first green sovereign bond in September, investors placed more than £100bn in orders, beating all previous records for debt sales by Westminster.

Kidney notes that other factors have been whetting the market’s appetite for sustainable investment. Joe Biden’s arrival in the White House has been particularly useful. “You now have a US president who is treating climate change as his number-one challenge,” he says.

Biden held a climate summit in April at which many big economies committed to tough new 2030 targets, notes Kidney, who adds: “You’ve got all the world’s power blocs going green and suddenly people are asking: ‘How do I make money out of this?’”

Suddenly, every sustainability manager of an investment fund around the world has become popular

New taxonomies are being developed around the language of climate change, which helps to clarify how green bonds can be used. The US, China and the EU are among those to have given clearer definitions as to what can be called ‘green’, according to Kidney. “This is no longer the Wild West. We’re starting to see some pretty robust governance mechanisms.”

Kidney sees a central role for development banks in maintaining the momentum. “They’re public-sector pools of capital that can be the buffer between private-sector risk challenges and what’s got to happen,” he says. “They’ve just got to be reoriented for a greener mission” by ensuring that money is being put into sustainable infrastructure projects that will help to achieve the climate goals set by the UN’s 2015 Paris accord.

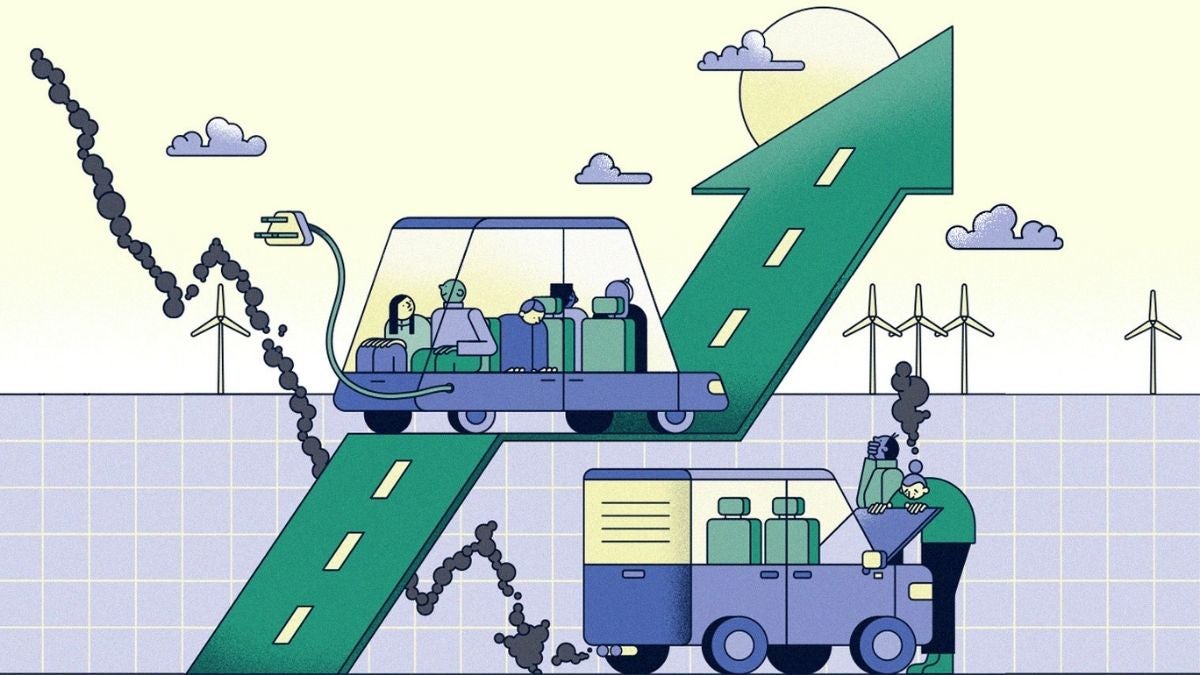

Appropriate investments could include green transport systems, energy-efficient houses, offshore wind farms and projects that improve climate adaptation, such as flood defences and regenerative agriculture.

Kidney notes that the greening of many emerging economies will soak up a lot of capex. There are opportunities for investors such as pension funds to make a lot of money here, but “development needs to be integrated with climate initiatives”, he stresses, referring to the new wave of African mega-cities, where billions of pounds have already been poured into building roads, rather than railways. He also cites the decades that some emerging markets have spent building inefficient “glass towers” that rely on air conditioning to make them usable. Over the past 20 years, just as much money has been spent on air-con systems in tropical countries as it has on renewable energy.

Kidney says he would like development banks to be rebranded as climate banks, pointing to the EIB as a good example of what can be achieved. Half of the bank’s annual €80bn (£68bn) investments now go towards climate initiatives, while it ensures that none of its other investments works against the Paris accord. “Every bank, not only development banks, should be doing that,” he argues.

Ultimately, Kidney’s experience of sustainable investment has left him with a curious mix of optimism and scepticism. With a year-on-year increase of 16% in global CO2 emissions expected for 2021 at a time when they should be dropping by 8%, “the truth is that the climate figures are not going our way”, he says.

But Kidney adds that “green bonds give me hope – I do think we’re making progress. Yet we’re so late to this party. There’s no doubt about where we’re going – the shape of the future is decided – the problem now is our speed. We’ve got to get there really fast.”

“In every investment call I have, people say: ‘Give me more green bonds,’” says Professor Sean Kidney, co-founder and CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative. “That makes me hopeful. Green bonds have grown up.”

His organisation is a not-for-profit body working to mobilise international capital for climate action. It works in more than 30 countries with partners including BlackRock, Allianz Global Investors and Credit Suisse, as well as advising several national governments.

The first ever green bond, designed specifically to raise money for environmental projects, was issued in 2007 by the EU’s European Investment Bank (EIB). Having grown steadily since then, this market is now valued at nearly £1.1tn.