In January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted Britain would be the only major economy to contract in 2023. Back then, it believed a 0.6% decline was likely, putting the UK behind even international pariah Russia.

Just a few months later, the IMF has revised its estimates upwards. It now expects UK economic output to grow by 0.4% this year, a bigger increase than Germany’s. This sounds like good news, but several other key economic indicators show the UK’s economic performance is something of a mixed bag.

For instance, although GDP dipped slightly in May, the country has so far avoided recording a technical recession (two successive quarters of contraction). Unemployment remains about as low as it’s been since records began. Equity markets are also holding their gains, with investors in the FTSE 100 index seemingly in a bright mood.

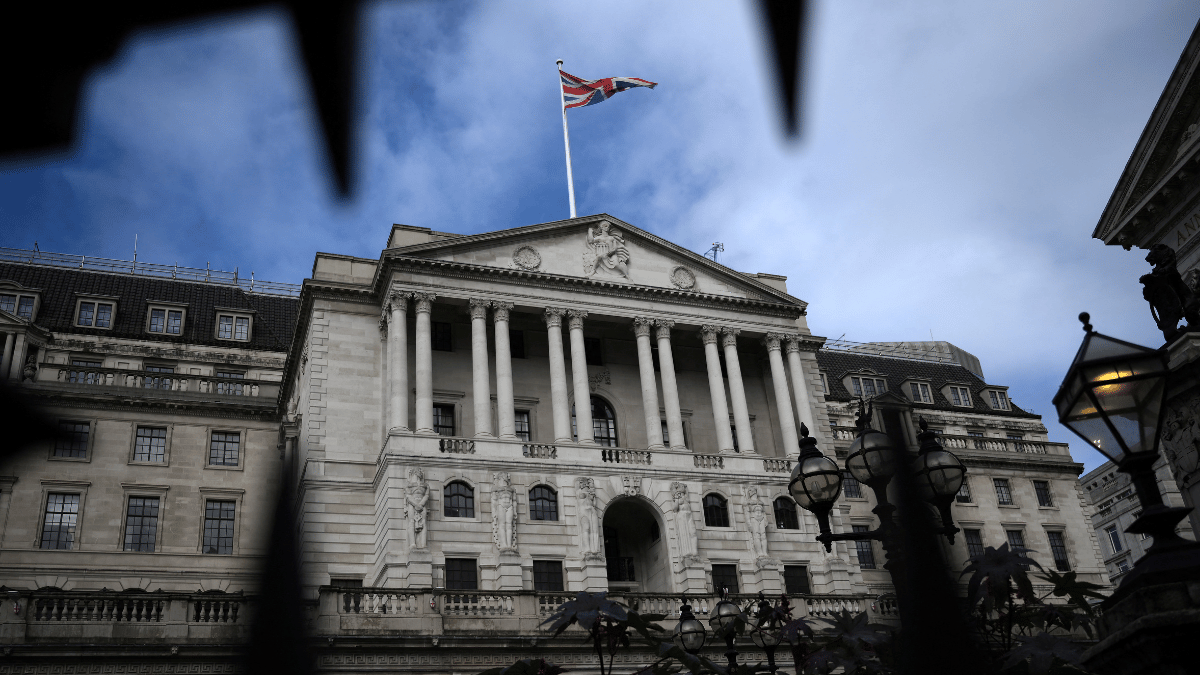

Earlier this month (July), the Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, acknowledged that several of its gloomiest predictions – including a two-year downturn – had proven inaccurate. “The UK economy has shown unexpected resilience in the face of … substantial – in some cases unprecedented – external shocks,” he told financial services chiefs.

But are we entirely out of the woods? The UK is still facing a unique combination of problems. As Mark Carney, the Bank’s previous governor, noted earlier this year, the triple pressures of energy price inflation, the pandemic and Brexit have “weighed on the economy”, forcing policy-makers to balance getting inflation under control with keeping the impacts bearable for ordinary people.

That makes concluding whether the UK economy has turned a corner or not difficult. Here, we analyse the data.

GDP growth: stagflation ahead?

There are positive signs in the big-picture economic data. GDP fell by a less-than-expected 0.1% in May following a slight rise of 0.2% in April. The Office For Budget Responsibility has revised its economic forecasts upward since last November, although these are still less optimistic than a year ago. The British Chambers of Commerce likewise says it has seen a “rebounding of business confidence” in recent months and no longer predicts a recession for this year.

Others are less sanguine. Major asset manager Legal & General said this week it is betting on a “significant” downturn in the UK and global economies as rising interest rates put the brakes on investment and spending.

The UK may be facing a “poisonous cycle” of stagflation – high inflation combined with low growth – says Giles Coughlan, chief market analyst at the HYCM Capital Markets Group. The economy is “hovering around breakeven point,” he adds. “If we win the inflation battle, we’ll probably avoid a recession. But I wouldn’t be surprised if we gently dipped into one.”

Inflation: barely under control

Managing inflation, which started rising in late 2021 and was then fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is key to solving the UK’s economic woes. Although the rate of inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, dipped last month for the fourth month running, it is still almost six percentage points above the Bank of England’s target of 2%.

Economists are worried about inflation becoming “sticky”, particularly because core inflation (which excludes food, energy, alcohol and tobacco prices) is not falling as fast as overall CPI. That’s despite countries such as the US and France managing to bring their price rises below 5% in recent months.

Getting a handle on the crisis is at the top of chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s to-do list. He admitted this month that the Conservatives’ promise to halve inflation by the end of 2023 would be a greater challenge than expected. However, he must juggle that priority with growing clamours for tax cuts and wage increases, particularly in the public sector, both of which could fuel further price rises.

Interest rates: a tricky balancing act

Central banks in many economies have increased the cost of lending in their efforts to control inflation. The Bank of England has been more aggressive than most, increasing the base rate 14 consecutive times since 2021.

That base rate is now at 5%, the highest level in 15 years. The rate is likely to climb again this year but is now thought unlikely to hit 6% or more, as was recently feared. That’s relatively good news for mortgage-holders and renters, as well as businesses, where these increases have put severe constraints on business investment.

“Because inflation is so high, rates have to be high to crush that demand,” says Coghlan. “The only tool the banks have to combat it is to keep hiking interest rates more aggressively, but that’s going to result in greater hardships and drag down growth. But how else do you cool demand?”

The labour market: running hot

Another factor that would cool demand is a significant increase in unemployment, which helps businesses to save on wage costs. But the labour market is tight, with record numbers of both job vacancies and people in work, despite many people returning to work.

The OBR predicted in November 2022 that unemployment would increase by 50% (equivalent to about 650,000 people) by mid-2024. But in its March update it revised that downward to just 15%.

While good news on a human level, it might not benefit the wider economy. A tighter labour market leads employers to boost wages. This can actually prolong inflation, because it increases costs for businesses while enabling more people to afford higher prices. This effect is known as the “wage-price spiral” and can be difficult for an economy to shift.

Consumer spending: more belt-tightening ahead

British consumers are keenly feeling the hit to their disposable incomes. The latest data by market research firm GfK has found consumer confidence is almost as weak as it was during the depths of the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and the pandemic in 2020-21, despite a slight recovery during the first half of 2023.

GfK’s index takes into account people’s feelings about their own prospects and those of the economy. Joe Staton, its client strategy director, says the results show “reality has started to bite” for British residents, warning that “as people continue to struggle to make ends meet, consumers will pull back from spending.”

The FTSE 100’s revival: no silver lining

Despite consumer pessimism, many blue-chip companies have been performing strongly. Several high-street names, including Pret a Manger and Superdrug, have recorded bigger profits than expected over the past few months.

Meanwhile, the FTSE 100 index recently neared its all-time peak, falling only slightly since then. Shares in banks and consumer goods firms are particularly buoyant. But analysts warn this isn’t necessarily a sign of a strong economy.

As Coughlan points out: “A lot of the FTSE 100 earnings come from overseas. These are not reflecting the domestic economy.”

Comparisons with other stock exchanges also reveal a more disappointing picture. The FTSE 100 reached its record high back in June 2018 and has only recently got near that mark again. Over the same period, the US’s S&P 500 index has nearly doubled.

“Because of Brexit, no one wanted to invest in UK companies, so the FTSE has been depressed for a long time,” Coughlan says. “Now it’s having a bit of a rally because investors are seeing a recession heading into the US. Where can they find value? The FTSE 100 has been so beaten down that there are some bargains to be had there.”

Brexit: a continuing drag on trade

While the markets have all-but forgotten the disastrous mini budget from Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng last year, another political choice continues to reverberate through the economy: the UK left the EU’s single market in January 2021 amid the Covid crisis.

Since then, its international trade activity has been slower to recover than that of the other G7 members. British import and export values are still below their pre-pandemic levels. By contrast, Italy, Germany and Japan have all increased their commerce with the rest of the world.

Brexit has already cost the UK 4% of its GDP and about £100bn a year in lost output, according to Bloomberg.

“As a nation, we haven’t exactly worked out a clear post-Brexit direction – and that‘s started to affect our output,” Coughlan says. “The projections are pretty bleak.”

In January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted Britain would be the only major economy to contract in 2023. Back then, it believed a 0.6% decline was likely, putting the UK behind even international pariah Russia.

Just a few months later, the IMF has revised its estimates upwards. It now expects UK economic output to grow by 0.4% this year, a bigger increase than Germany's. This sounds like good news, but several other key economic indicators show the UK's economic performance is something of a mixed bag.

For instance, although GDP dipped slightly in May, the country has so far avoided recording a technical recession (two successive quarters of contraction). Unemployment remains about as low as it’s been since records began. Equity markets are also holding their gains, with investors in the FTSE 100 index seemingly in a bright mood.

Earlier this month (July), the Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, acknowledged that several of its gloomiest predictions – including a two-year downturn – had proven inaccurate. “The UK economy has shown unexpected resilience in the face of … substantial – in some cases unprecedented – external shocks,” he told financial services chiefs.