In February, 400,000 steelworkers were put on notice. Not in Port Talbot or Redcar, but in China’s smoke-clogged industrial cities. In total this year, an estimated 3 million people will lose their jobs as the country tries to scale back the heavy industries that powered its growth, but which have now become an expensive liability.

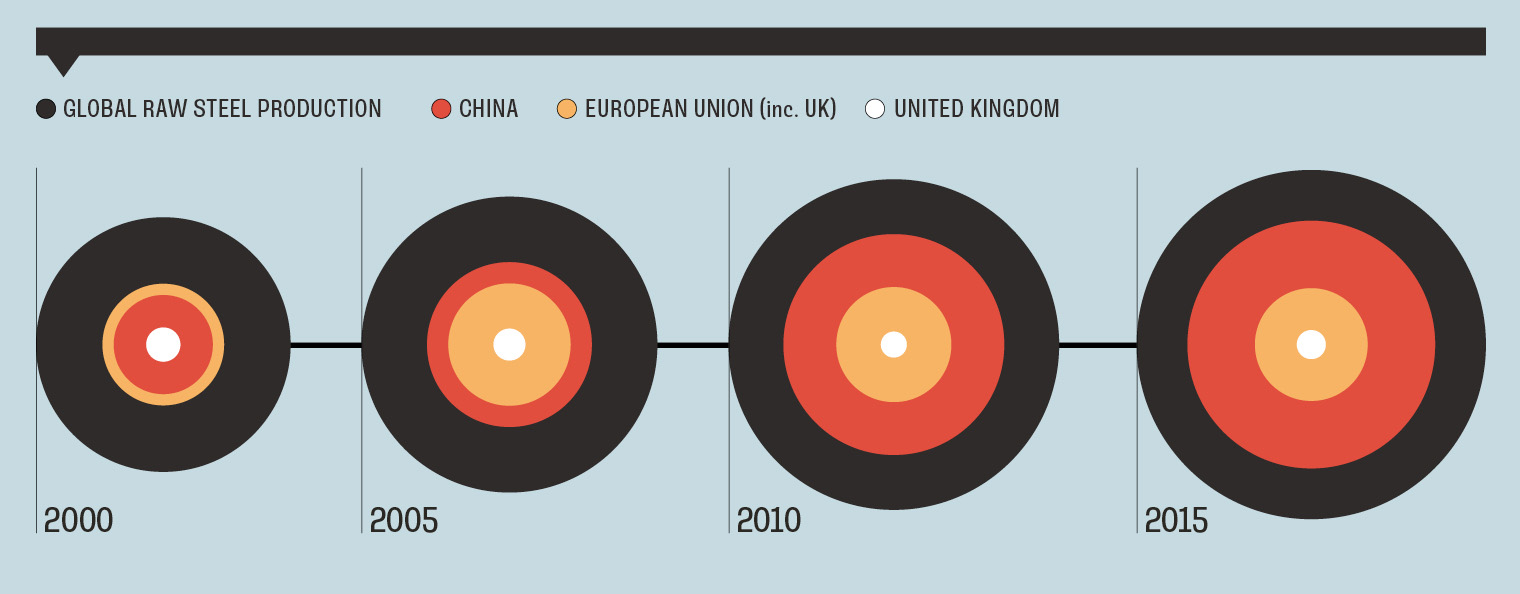

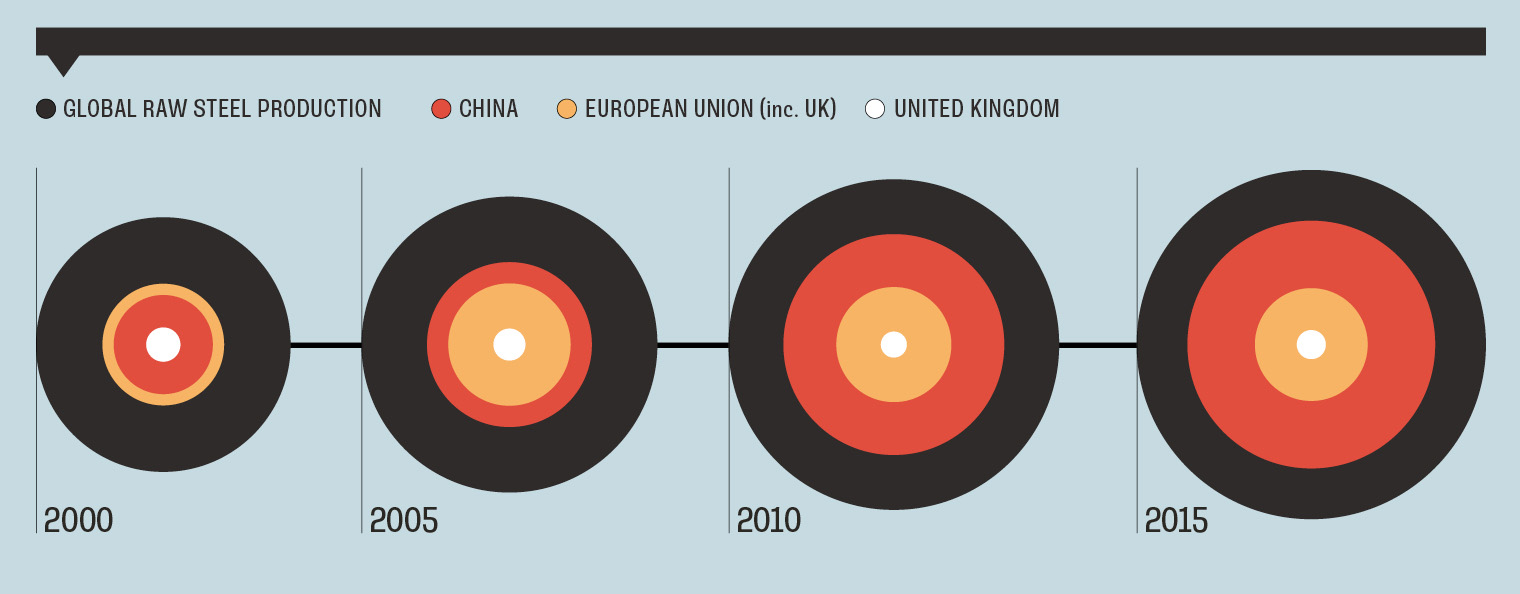

Since the turn of the millennium, China’s steel output has grown from 15 per cent of global production to more than half, as enormous national infrastructure projects and a rapidly-expanding manufacturing sector drove demand.

Now the Chinese economy is slowing — this year, growth will be its lowest for 25 years — and the country faces an enormous oversupply of steel, which is being dumped onto world markets, forcing down prices.

Last year, Chinese steel exports topped 100 million tonnes for the first time — a more than 20 per cent increase on 2014. This, in turn, is creating waves in the global market that are breaking on the UK’s already beleaguered steel sector, most recently on the Port Talbot steelworks in Wales, which has been put up for sale by its owners, Tata Steel.

European governments have lined up to censure the Chinese government for artificially altering the dynamics of the market. The EU imposed some anti-dumping duties on some Chinese steel products last year and delayed a decision on whether to grant the country ‘market economy’ status, which would have given it greater trade rights.

[embed_related]

UK foreign secretary Philip Hammond told the press in early April that he has lobbied the Chinese government to speed up its production cuts, but, according to Merlin Linehan, a consultant specialising in China’s trade with the rest of the world: “They’re not going to do it because everyone else is telling them to… They don’t want any social unrest, that’s the overriding fear behind any economic decision,” Linehan says.

“That’ll be the deciding factor. They’ll move things offshore, close down polluting factories — the older, less efficient ones — but at a gradual pace to alleviate unemployment problems.”

[tweetThis text=”I wouldn’t say that China’s going to shut down steel plants just because the UK is unhappy”]

The British steel industry has been in a slow-burning crisis for months. The Redcar steelworks on Teeside, owned by the Thai company SSI, shut last September, with the loss of 1,700 jobs. Tata Steel, the India-headquartered conglomerate which owns the factory in Port Talbot, has put most of its UK operations up for sale. Investment company Greybull Capital has agreed to buy part of the business, saving around 4,400 jobs.

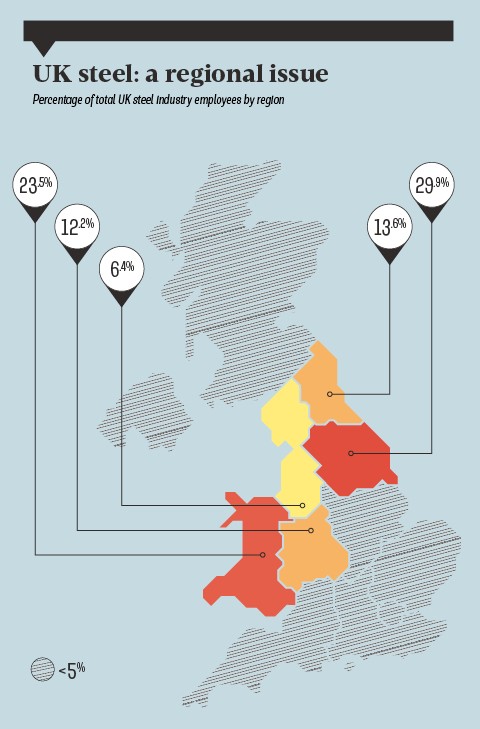

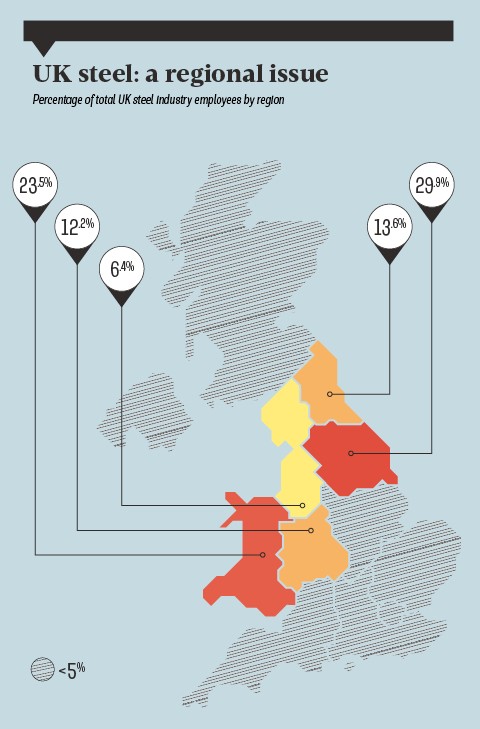

The steel business has been a dwindling contributor to the overall British economy for decades. In the early 1970s, the industry employed around 320,000 people; today it is a little over 10 per cent of that. However, where those jobs are based makes saving the industry more than just an economic consideration.

More than half of the total roles are in Wales and in Yorkshire and Humberside, with a further 14 per cent in the North East — all areas that have suffered from the UK’s move from an industrial to a service-led economy.

Unfortunately, this is China’s problem as well. As Andrew Batson, China research director at Gavekal Dragonomics in Beijing, explains, the country’s steelworks are concentrated in a small number of areas, meaning that job losses will be acutely felt, and could cause considerable tension.

“I think it’s less the absolute amount of layoffs — which are frankly a drop in the bucket where the total workforce is around 700 million people — and more the fact that the impact is very disproportionate on some areas that therefore has social consequences,” Batson says.

This means that the pace of restructuring is unlikely to accelerate, and that while Beijing and Chinese steelmakers might be cognisant of the longer-term trade implications of its current policy, it is unlikely to change it. “I wouldn’t say that China’s going to shut down steel plants just because the UK is unhappy,” Batson says.

China’s runaway train

China’s rapid economic growth over the past two decades has been driven by its enormous industrialisation and infrastructure development. To support that, it has enormously expanded its steel production, backed by state funds and quasi-national companies. Now, with growth slowing, it has a production overhang that is costing billions of dollars.

Photo:STR/AFP/Getty Images

China’s runaway train