RAF Cardington is an empty scrap of scrub on the outskirts of Bedford, marked by two vast olive green hangars, each well over 100m long. Abandoned for decades, the facility, which was the centre of the UK’s military airship industry in the early 20th century, is occupied again – inside, a colossal, double-hulled dirigible, a glass cockpit nestled in the gap between the two noses, floats a few metres from the ground. The Airlander 10 is expected to make its maiden outdoor flight in the coming months, as its owner, Hybrid Air Vehicles, tries to move the vehicle from a curiosity into a genuine commercial prospect.

Dirigibles had a romantic history in the early age of air travel, although high-profile disasters — in particular that of the Hindenburg, which went down in flames on film in 1937 — and the rise of faster, safer passenger aeroplanes ended their mainstream use. Occasional attempts to revive the airship using inert helium, rather than explosive hydrogen, continued throughout the latter half of the 20th century, according to Stephen McGlennan, CEO of Hybrid Air Vehicles.

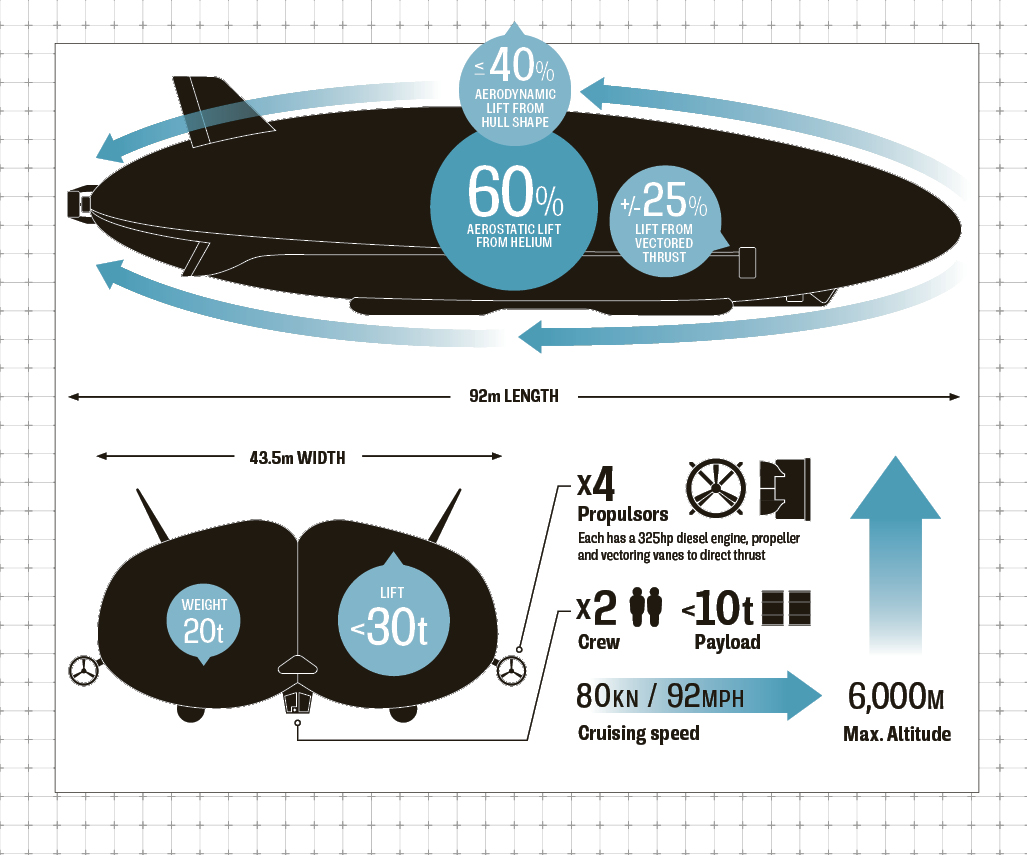

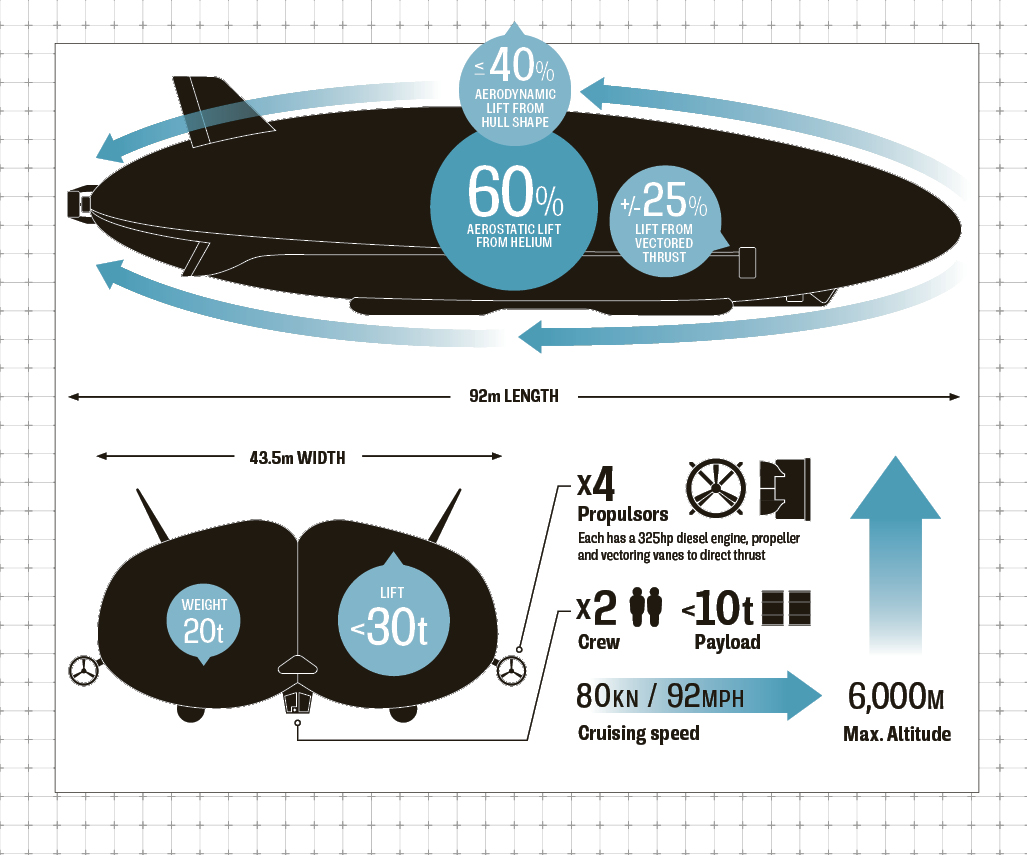

“By the time they got to the year 2000, people had worked out that airships themselves were a bit of a dead end. However, they struck on the idea of taking elements of the airship and elements of fixed-wing technology, and then the vector thrust of the helicopter,” he says. “You put those things together and you’ve got a modern airship that took the benefit of helium but not the disadvantages.

“They got to the point where they were flying around a 45-foot [13.5m] remote-controlled model for years and years.” By then, it seemed as though the “hybrid” airship was destined to be another good idea whose time simply had not come. Then the US invaded Afghanistan. As the war evolved, too many troops were being injured and killed by improvised explosive devices, and the government threw money at a broad spectrum of potential technological solutions. One was an eye in the sky — a vehicle that could stay up for days at a time and monitor the ground for insurgent activity.

The airship can be configured to carry up to 48 passengers

“This technology came out of that. They scaled it up. The idea was simple. Fly for three weeks over an area, film it all the time, process the film for the patterns of life which equate to the burying of a bomb. Go and deal with the bomb,” McGlennan says. “We built it, we flew it. Then they came out of Afghanistan and cut the programme.”

Today, McGlennan is philosophical about the sudden loss of funding. This is a big idea, he says, and in the history of big ideas in engineering, “shit happens”. “We always owned the intellectual property. We asked them if we could have the aircraft,” he says. “To their immense credit, the US Army sold it to us.” The Airlander’s real breakthrough is in the material that makes up the hull.

Instead of the simple cylinder shape of an older Zeppelin, the Airlander is a bulbous flying wing, wider than it is deep and cambered to create lift, something that would have been impossible to build with the flexible materials used in old dirigibles. This, along with improving communication technology, amount to “a renaissance point for lighter-than-air [vehicles],” according to Mike Durham, the company’s technical director.

“There’s no doubt there’s a bit of a giggle factor with airships. We’re trying to show that this is a serious alternative to other types of aircraft. It’s got its niches,” Durham says. “It’s never going to get rid of aeroplanes and helicopters, but it’s got some really nice niches.”

Many of those niches will be back in the military. The company has commissioned independent research, which estimates the total size of the market at 600 vehicles over the next couple of decades, 40 per cent of which will come from the armed forces. The cost, at £25 million per airship, makes it a serious investment, but the vehicle’s military upbringing means that it is pretty robust. As Durham says: “If it’s had 100 bullet holes through it, it’ll fly for another five or six hours. It’s a pretty safe form of flight. Failure modes are a lot less horrible than an aeroplane. Four engines go out on this, it’s not very exciting.”

The Airlander can also carry heavy loads — around 10 tonnes currently, although this could rise once the company scales it up further. Fuel consumption is a tiny fraction of that used by an aeroplane, and the engines could be configured to be entirely electric, making it a cleaner, quieter, albeit slower, form of transport.

McGlennan sees the Airlander more as “a transit van” than a haulage lorry — its users will find new ways to build businesses around it. Telecoms companies might look to use it to carry mobile phone masts over music festivals; tour companies could use its passenger capacity to run airborne cruises.

Whether the Airlander can move beyond the prototype stage depends a lot on public perception. Chris Atkin, president of the Royal Aeronautical Society, says that the discussions about the use of delivery drones show that people are at least open to new modes of air transport. Part of the company’s funding has come from crowdsourcing — adding to larger stakes taken by private investors, including aircraft-obsessed Iron Maiden singer Bruce Dickinson.

“The market is ready,” Atkin says. “The public is starting to think that they might have quad-copters dropping off packages. In the same way, the heavy-lift community might be thinking, actually, this is quite useful.” Not everyone may be on board just yet. At the security post outside Cardington, a car has pulled up. The driver, a saleswoman on a cold call, leans out to ask the guard what is going on inside the giant hangars. He explains. “Oh,” the driver says, looking suspiciously through the wire. “Airships? Like the Hindenburg?”