Two-year-old Musa Irfan Taj wails quietly on a bed at Lahore’s Sheikh Zayed Hospital. A line of dried blood curls down his neck as nurses mill around him with notepads. On March 27, Musa was queuing in line to play on swing-sets when a suicide bomb detonated, killing more than 75 and injuring over 300 people during the Easter Sunday attack. “I never thought this could happen,” his mother says.

Musa sits dazed and fearful, his father lying supine on another bed. Nearby, a lone child, 10-year-old Atiqa Shoaib, sips a McDonald’s smoothie through a plastic straw. Her parents have already left the emergency ward, leaving her alone as she slowly recounts the ages and names of her kin.

“In Pakistan, there is no security,” say Farhat Nasir, watching the scene. “My children aren’t safe. I need security.”

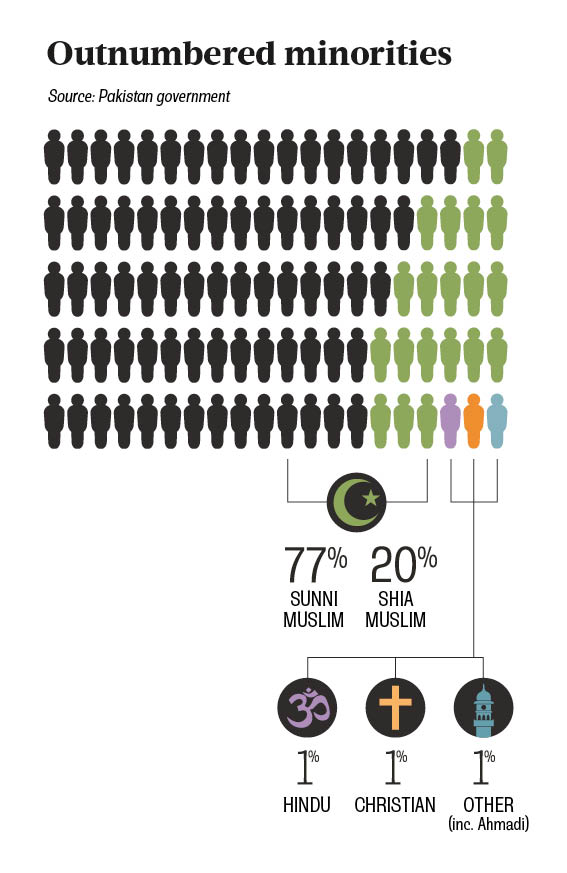

The attack on the Gulshan-e-Iqbal park was orchestrated by a splinter group of the Pakistani Taliban called Jamaat-ul-Ahrar; they identified Christians celebrating Easter as their primary target. Although Pakistan has not held a census in more than a decade, the nation of 180 million is home to large minority populations, including 2.5 million Christians, 2 million Hindus, and 2 million Ahmadis, a self-declared Muslim group deemed non-Muslim by Pakistan’s constitution.

For Christians, the last few years have seen a precipitous uptick in violent attacks, despite a downward trend in terrorist incidents in Pakistan itself. Last year, twin bombings targeted churches in the Christian enclave of Youhanabad, leaving scores dead and over 70 injured. In 2013, the All Saints’ Church in the frontier city of Peshawar was also attacked, killing more than 80 people.

“These are not just attacks on Christians; these are attacks on everyone,” says Shahid Saleem, a 37-year-old Christian rickshaw driver, as he drives to Lahore’s Joseph Colony, a largely Roman Catholic community that is hemmed in by steel mills. “They look for targets wherever they are, mosques or churches. No one in Pakistan is safe.”

The entrance to Joseph Colony

In Joseph Colony, one-room churches are squeezed into the colony’s narrow gullies, with barefoot congregants singing hymns in Urdu. On Sundays during church service, the presence of outsiders entering the community is heavily monitored; one gate is closed altogether, while the other is guarded by armed police.

Before major holidays, the police dispatch one or two officers to each church and circulate leaflets asking churches to install CCTV cameras, metal detectors, and tall boundary walls. Most Lahore church-leaders admit they cannot afford the expense. Instead, an all-volunteer phalanx of Christian men patrol the church during service hours.

BLASPHEMY AND INTOLERANCE

In 1947, when Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, delivered his first presidential address to the national assembly during the country’s creation, he famously said: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed.”

In the weeks before the Easter Sunday attack, echoing Jinnah’s sentiment, Pakistan officially recognised Easter, Holi and Diwali as public holidays for the first time in its history. These symbolic gestures signalled that a multi-confessional Pakistan was not off the table.

In fact, Pakistan’s parliament had even tried to bring marginalised communities into the political fold by reserving 10 National Assembly seats for non-Muslims; the Senate requires one seat to be allocated to a minority from each province. In practice, however, the minority electorate views non Muslim politicians as puppets cherry-picked for ruling parties.

Even the prime minister cannot protect our safety. He looks out for himself, not for Christians… In Pakistan, no one is safe

“Even the prime minister cannot protect our safety. He looks out for himself, not for Christians,” says Mariam Emmanuel, a student standing near the Joseph Colony gate. Her mother Maseem mans a kiosk close to the entrance. After the recent insecurity, Maseem hopes to move out of Joseph Colony, where she cannot safeguard the wellbeing of her offspring or fellow citizens. “In Pakistan, no one is safe,” Mariam explains.

Three years ago, the predominantly Christian community of Joseph Colony was torched by a frenzied mob seeking vigilante justice. Their target was a Christian man, Sawan Masih, who they claim had insulted Islam. The punishment was profound: 200 homes were transformed into a blackened pit of charred masonry and mangled metal. Today Masih is slated to face the death penalty, and Joseph Colony is still reeling from the aftermath.

Maseem Emmanuel outside her kiosk near the Joseph Colony entrance gate

Nabila Ashraf, 40, remembers that day clearly. With her hair pinned back and a deep pink salwar kameez draped over her stout frame, she mostly lies on her charpai, an intricately-knotted wooden bed that sits opposite a poster of Jesus.

She once had a real bed, but that was incinerated by the mob. Ashraf remembers that local police had rapped on her door, telling the family to seek safety. The mob was uncontrolled, they had said, and would likely return the following day to inflict greater damage. Nabila and her children fled, carrying only the clothes on their backs. Her precious dowry, full of her most valuable fineries and goods she received during marriage, was long gone.

She remembers turning on the television and watching men pillage the small Christian community. In a frenzy, the men had doused flammable chemicals over her possessions and burnt her house’s gate down. The crowd even pilfered the motor on her 40,000-rupee (L265) refrigerator, which she was still paying for on instalments. “I had to start from scratch,” Nabila says.

When they stepped back into their home, the scene that awaited the family removed all sound from their throats, says her husband, Ashraf Sohan, a driver. Three years later, Ashraf watches his seven-year-old son Usman play on the chair nearby.

Only a few of his classmates at Usman’s mixed-faith school know that he is a Christian. Asked about interfaith relations at his school, Usman mischievously defends his secrecy: “Nobody bothers me at school — I bother them!” Yet his father says Usman’s future is better overseas — if he can get there — as the prospect of equal treatment in Pakistan is dim.

For Saleem the rickshaw driver, the 2013 Joseph Colony burning taught him to bite his tongue, in case false accusations fly toward him: “I never approach religious topics with people because I can get into trouble,” he explains, saying anti-Christian invective is commonplace, but requires him to take the higher road.

“I never approach religious topics with people because I can get into trouble”

The blasphemy law carries the death penalty in Pakistan, and many religious minorities fear a trivial argument, or a land or property dispute, might devolve into blasphemy accusations. In 2009, a Christian woman named Asia Bibi allegedly imbibed water from the same utensil used by Muslims, and reportedly made statements about the Prophet. Today, she sits on death row for blasphemy charges.

Her case was taken up by Punjab governor Salman Taseer, who was assassinated in 2011 by his bodyguard Malik Mumtaz Qadri. In February 2016, the government quietly hanged Qadri, sparking mass protests countrywide. In the days after the March’s Easter Sunday attack in Lahore, thousands of Qadri’s supporters rioted on the streets, demanding the execution of Asia Bibi during sit-ins in front of parliament.

Despite inter-communal tension, there are signs of that coexistence is possible. Khalida Parveen, a Muslim housemaid, sweeps Nabila’s home. In a country where most Pakistanis view Christians as part of a sweeper class, encountering a Muslim servant in a Christian home is rare.

“There’s no problem,” Parveen insists, laughing affectionately next to Nabila and noting that Christians are Ahl-al-Kitāb, or People of the Book. “It’s written in the Quran that if you want to eat or sit with Christians, you can.” Parveen adds that she ate breakfast with the Ashraf family that morning — no small gesture in a country where some Muslims still refuse to eat or drink with Christians, and the most inflexible of restaurant owners ask Christians to pay for plates or spoons

because they are deemed unclean and no longer usable.

[embed_related]

CONSTITUTIONAL DISCRIMINATION

In Pakistan, the president or prime minister is required to be Muslim by law. When the country amended its constitution in 1974, another religious group lost out: the Ahmadis, who were declared non-Muslims by the state. Like Christians, Ahmadis have faced targeted violence at the hands of extremist groups, but the most acute has been at the hands of the state itself, which has made it a crime for Ahmadis to label themselves Muslims.

In 1889, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad founded the Ahmadiyya movement in modern-day India, professing to be a messiah. From that moment, orthodox Sunni Muslims have opposed the group’s religious claims, arguing that the Ahmadis reject the finality of Prophet Muhammad.

Today, even applying for a Pakistani passport requires an Ahmadi citizen to disclose their identity. “You have to sign an affidavit saying the leader of the Ahmadis is an imposter,” says Ali, an Ahmadi in Lahore who asked for his real name not to be disclosed. “I cannot write he is an imposter.” For those who do not agree with this statement, a blank page on the passport is labelled “Ahmadi”.

According to Ali, the separation of Ahmadis starts even earlier in Pakistan’s education system. While taking the final exams for completing secondary education, Ali recalls filling out a form asking for his religion. “You have to be registered as an Ahmadi right from the matric exam slip,” he says.

“As citizens of Pakistan, under the constitution, Ahmadis are equal citizens,” says Muhammad Arshad, director-general at the Ministry of Human Rights. “The constitutional and legal protection

is there, but sometimes practically, the culture and social issues get in the way.”

Nonetheless, all across Lahore, religious minorities paint a picture of legal and social insecurity. For Ahmadis, the recent Easter Sunday attack was another reminder of the government’s failure to protect its most vulnerable. Ahmadis don’t need to rewind the clock too far to remember their own tragedy: in May 2010 in Lahore, up to 100 people were killed when the Pakistani Taliban targeted two Ahmadi mosques. After this incident, some Ahmadis bought guns, realising that the police would not protect them.

Ahmadis have too recruited volunteer guards — some armed, others not — during prayer services. Some Ahmadis go underground, congregating in private homes, which shift on a rotating basis, with neighbours left entirely in the dark about the purpose of the gathering. This is partly because Ahmadis are banned from building mosques or ‘posing’ as Muslims. Ahmadis who build a mosque are subject to prison terms for up to three years. For this reason, the community is careful to ensure that even construction workers on an Ahmadi worship site are Ahmadi to prevent maps from leaking out, Ali says.

Today, there are approximately 2-3 million Ahmadis in Pakistan. However, the leadership — represented by the Khalifa — lives in exile in London, due to a 1984 ordinance rendering it illegal for any Ahmadi in Pakistan to call himself a Khalifa.

The result is a 30,000-strong diaspora of Ahmadis in the UK. Religious friction does not fade in the diaspora, however, and in March an Ahmadi shopkeeper, Asad Shah, was murdered in an attack linked to his religion.

In Pakistan, deteriorating security conditions for religious minorities has led to most Ahmadis and Christians learning to practice their religion below the radar, seeking out as little attention as possible from either the public or the state.

Pakistan, aware of the precarious social position of millions of minorities, went so far as to create a special commission last year to safeguard minority rights, housed under the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Yet back in Joseph Colony, Ashraf is unconvinced by the efficacy of these schemes, and remains skeptical of government quotas promising seats to minorities: “If we apply for some government job, they see our file with our religion and ask us to wait outside,” he says. “Sometimes we will wait for the whole day.

“Nobody raises their voice for Christians. We are living here in a state of fear.

BLASPHEMY AND INTOLERANCE