In November last year, a team from McGill University in the US searching through signals picked up by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico found an odd, repeating pattern. These ‘fast radio bursts’, or FRBs, had been detected before in isolation and were assumed to be the result of cataclysmic events far away, such as supernovae.

The Arecibo results, released in March 2016, showed 10 FRBs, apparently from a single source outside our galaxy, suggesting that rather than the result of a destructive event, they came from something that was recharging itself. Immediately, the speculation began: were these pulses signals created by alien technology?

There are more likely explanations, but dedicated researchers have been scanning the skies looking for radio waves for more than two decades, hoping to pick up evidence of alien civilisations.

Source: University of California, Berkeley

“We look at tens of millions of channels at once, but what we’re looking for is the signal that’s essentially only in one channel, that’s at one frequency — that’s at one spot on the radio dial,” says Seth Shostak, senior astronomer at the SETI Institute in California, which is part-funded by NASA. “That’s the sort of signal that transmitters make, but nature does not.”

Although it is unlikely that anyone on Earth would be able to decipher the meaning of any transmission, we should be able to recognise it as an artificially-generated signal. As Shostak says: “It’s very hard to pick up the message, but it’s not so hard to pick up the bottle the message is in.”

SETI has been analysing radio signals since the 1990s, and since 1999 has borrowed idle computer power from the public to do so through an enormous distributed computing project, SETI@home.

Source: University of California, Berkeley

This month, the institute announced a new phase of its search, an expanded analysis of 20,000 ‘red dwarf’ stars — small, cold stars that were previously thought incapable of supporting life.

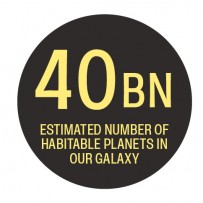

The search for extraterrestrial life had previously focused on stars similar to the sun, with researchers working on the assumption that they posed the best chance of producing an intelligent civilisation. Over time, however, that logic has started to look flawed. Red dwarves are as likely to have planets orbiting them as sun-like stars, and those planets could, in theory, be habitable, Shostak says.

There’s so much real estate that if there isn’t life out there, then there’s something very odd about the Earth

Red dwarves are also far more common and far longer-lived than sun-like stars, meaning that civilisations may have had time to develop on planets around them.

Although years of scanning the sky are yet to yield results, Shostak is convinced that the search will eventually prove worthwhile. “The experiment keeps getting faster as computer technology advances. That’s why I’m optimistic, because in the next two years we’ll collect more data than we have in the previous 50,” he says.

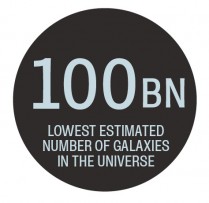

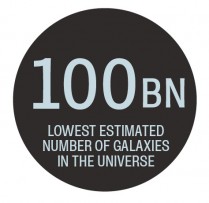

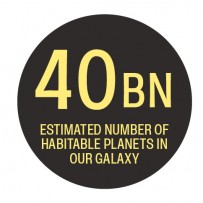

“Seventy to 80 per cent of stars have planets. That makes for a tally of planets that’s even greater than the number of stars. So that means there’s so much real estate that if there isn’t life out there, then there’s something very odd about the Earth, and it’s hard to understand what that might be.”

[embed_related]