Photo: Patrik Stollarz/AFP/Getty Images

On March 27, five days after suicide bombers killed 35 people in Brussels, text messages sent to young men in the city urged them to join the fight against les occidentaux — Westerners. The brazenness of Jihahi recruiters in Brussels, and particularly in the now-infamous Molenbeek district has been well-known for years, but the messages fed into a growing perception in Europe that Belgium’s radicalisation problem is out of control.

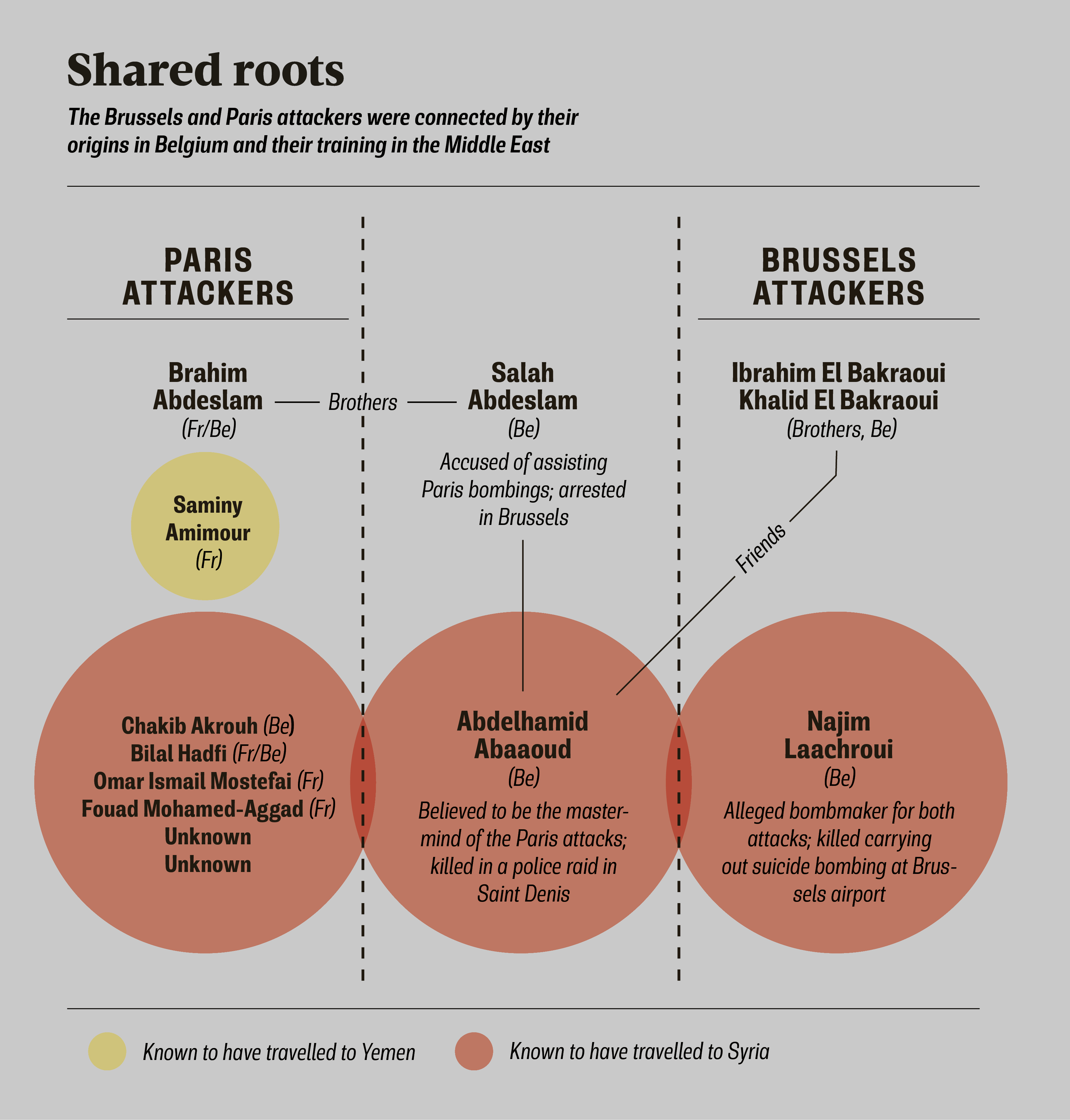

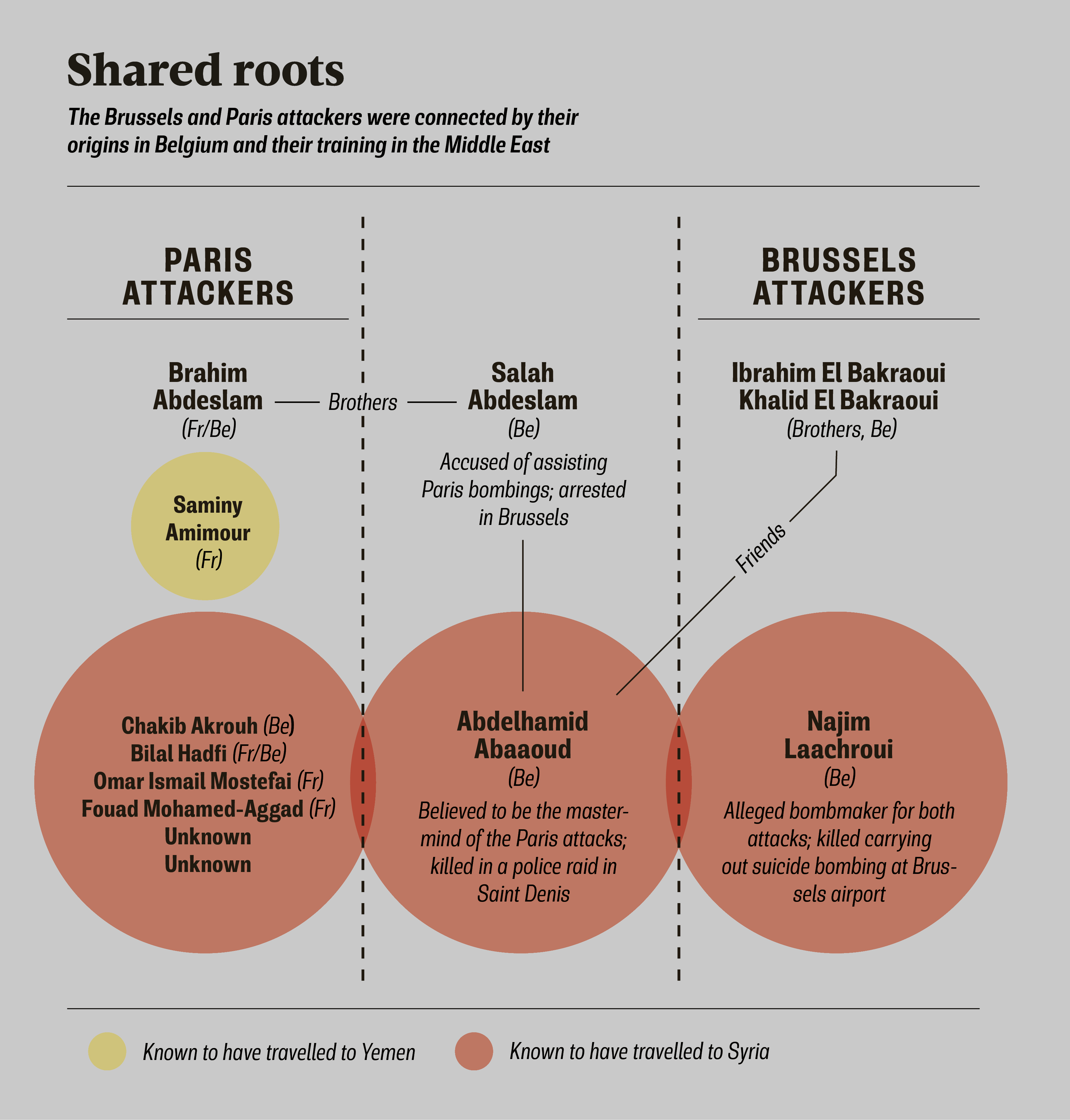

Two of the three bombers — brothers Ibrahim and Khalid El Bakraoui — were Belgian-born. Najim Laachraoui, who is thought to have been the bombmaker for the November attacks in Paris, and who blew himself up at Brussels airport, was born in Morocco but raised in Belgium. Brahim Abdeslam, who participated in the Paris attacks, and Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who allegedly masterminded them, lived in Molenbeek, as did Brahim’s brother, Salah, who is in custody in Belgium, accused of providing logistical support to the Paris attackers.

With few exceptions, the home-grown terrorists have been drawn from economically and socially disenfranchised communities. As Bill Tupman, an expert in transnational crime and terrorism, and honorary research fellow at the University of Exeter, says: “Radical Islamists seem to have worked out a strategy for radicalising people who are already isolated and deprived… Radical Islam appears to function in these communities in the same way as other types of [criminal] gangs.”

UK anti-terrorism professionals have told Raconteur that British police forces have been exploring the links between gangs and radicalisation for some time.

The El Bakraoui brothers were well-known criminals. Ibrahim had been released on parole in 2014 after shooting a police officer in the leg with a Kalashnikov while trying to rob a foreign exchange office. Khalid served time for armed robbery, car theft and the possession of firearms — again, Kalashnikovs. Salah Abdeslam and Abaaoud were both known as a petty criminals by Belgian police.

Just as gangs recruit in prison, so too do jihadists. Chérif Kouachi, one of two brothers who attacked the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, met his accomplice Amedy Coulibaly, who carried out a parallel shooting at a Jewish supermarket, in the Fleury-Mérogis prison. Both reportedly fell in under a more experienced extremist, Djamel Beghal, who was serving 10 years at the time for a failed plot to bomb the US embassy in Paris.

Radical Islamists seem to have worked out a strategy for radicalising people who are already isolated and deprived

“There’s an assumption on the part of the authorities that radical Islam and crime are in two different boxes, so you deal with criminals in one way, and you deal with radical Islamists in another. I think we’re beginning to realise that the border between them is breaking down,” Tupman says.

The success that jihadi recruiters have had in the suburbs, or banlieues, of Brussels and Paris has been exacerbated by a failure to coordinate between police forces and security services. The surprising speed at which military hardware flows into Belgium and France from the former Soviet republics on Europe’s periphery is matched by the apparent ease with which people have moved to and from Middle Eastern warzones.

Belgium, per capita, has exported more fighters to the Middle East than any other EU country. Official figures, released by the Belgian ministry of interior affairs in February, said that the government had identified 451 individuals linked to terrorist groups in Iraq and Syria. Of those, 269 were still believed to be in the Middle East, six were in transit, 117 had returned to Belgium and 59 had been detained while trying to leave the country.

[embed_related]

Along the line there were gaps that allowed the terrorists to slip through the net. Both of the El Bakraoui brothers had violated the terms of their parole and were wanted by police; Dutch authorities knew Ibrahim was being expelled from Turkey, but did not pick him up when he landed. Laachraoui, Salah Abdeslam and alleged accomplice Mohamed Belkaid were stopped at an Austrian border post in September, travelling on fake identification, but were allowed to pass. In November, in the immediate aftermath of the Paris attacks, Abdeslam slipped out of France and back into Belgium, despite being stopped at a checkpoint en route.

Cross-border coordination of policing, justice and social services in Europe has often been bogged down in the quagmire of national interests and sovereignty disputes. The same could be said of Europe’s ongoing crisis of growth, employment and economic equality, which has created the conditions that radical Islamist groups have been able to exploit.

As Tupman says: “We talk about Molenbeek, but if you look at any major European city, you’re going to have a district, or two or three districts, that have the same qualities. Since the financial crash, everything’s got worse.”