Over the past 20 years, many big corporates have adopted some of the ideas of the startup scene including a more egalitarian workspace design and working styles where management is treated the same as employees. This is a departure from the hierarchical design lay-out of the past where senior leaders were sequestered in luxurious, closed offices.

The origins of the open-plan environment synonymous with startups have much earlier origins in the 1950s when the Germans pioneered the idea of a Bürolandschaft (office landscape) which was a movement in open-plan office spacing.

However, the roots of a social-democratic approach to a working environment also came from Scandinavia with strong staff representation and employees having a greater voice in the design of the workplace, says Philip Tidd, head of consulting for Europe at Gensler.

“Scandinavian countries were early pioneers of open-plan environments in the 90s, and the UK took that baton and led the way into new ways of working to make open-plan more mainstream,” he says.

Corporate co-operation

There is no doubt that many large corporates have adopted open-plan workspaces in a bid to improve team work and collaboration, says Jeremy Myerson, director of WORKTECH Academy. “The reality is that unless the open plan is well thought out with a high degree of segmentation of different tasks and a high degree of choice for the individual that is not the case. A simple, low-choice, open-plan environment with an ocean of desks is not good for communication or team-working.”

The reason that many big corporates rushed to emulate the workspace design of startup firms was the attraction of co-working spaces, says Mr Myerson. “This was a new type of office organisation characterised by having a high degree of services and was much more like a club or restaurant where you would get subdued lighting, and it was curated with nice furniture. Big corporates want to encourage innovation and also want to interact with startups. Corporates are looking at incubator spaces as they need their people to innovate.”

Many corporates are trying to ape what is happening in smaller, startup technology companies, according to Mr Tidd. “Certainly, there are aspects of trying to mimic some of the more open managerial and leadership styles, but the bigger push for that openness in design is driven by real-estate savings.”

He cites Microsoft and GSK as examples of large corporates which have opened up their working environments and adopted a flatter hierarchy. “These two organisations have gone through that process of opening up their working environment for the last part of the decade. Their concept has evolved over time. They have gone through change in the last three to five years of adapting their own open-plan environment which has a rich variety of settings,” says Mr Tidd.

“GSK did a lot of work on breaking down silos that traditionally had space allocated according to hierarchy. A decade ago, Microsoft used to advertise ‘come to us and get your own office’. They’ve gone on a significant journey of change to make their own space a lot more youthful and attractive to a younger demographic. There is a lot more variety of settings and more project-based teams as well as experimental space for building products.”

It’s only the large organisations with a high degree of segmentation which have moved from a hierarchical model to a community-based one, argues Mr Myerson. “These spaces have a high degree of segmentation and there is community of purpose,” he says.

Traditional openplan environments are good for collaboration, but can pose a challenge for management by removing the obvious demarcation lines that exist in a hierarchical organisation

Office design

Mr Myerson believes there are three distinct phases of organisational design: command and control hierarchy; the rise of the egalitarian work community; and the networked organisation that is both physical and digital.

“The last phase is causing ructions in leadership style as you’ve got networks of co-employees, employees and freelancers, and an increasingly fluid group of collaborators,” he says. “Most companies are in transition from hierarchical to community to networked organisations. What is frightening for companies is the speed of networked organisations requiring new design and new responses to human resources and technology. The idea of rank and hierarchy is changing in networked organisations. It’s much more about the blurring of lines in an organisation.”

An open-plan working environment reflects an egalitarian structure to an extent, says Mr Tidd. “It’s about encouraging people to come out of their cubicles and closed offices, and to get more collaborative and transparent,” he says. “It’s definitely had a positive impact on the perception of staff that management is more accountable and encourages a sense of opening up of an organisation.

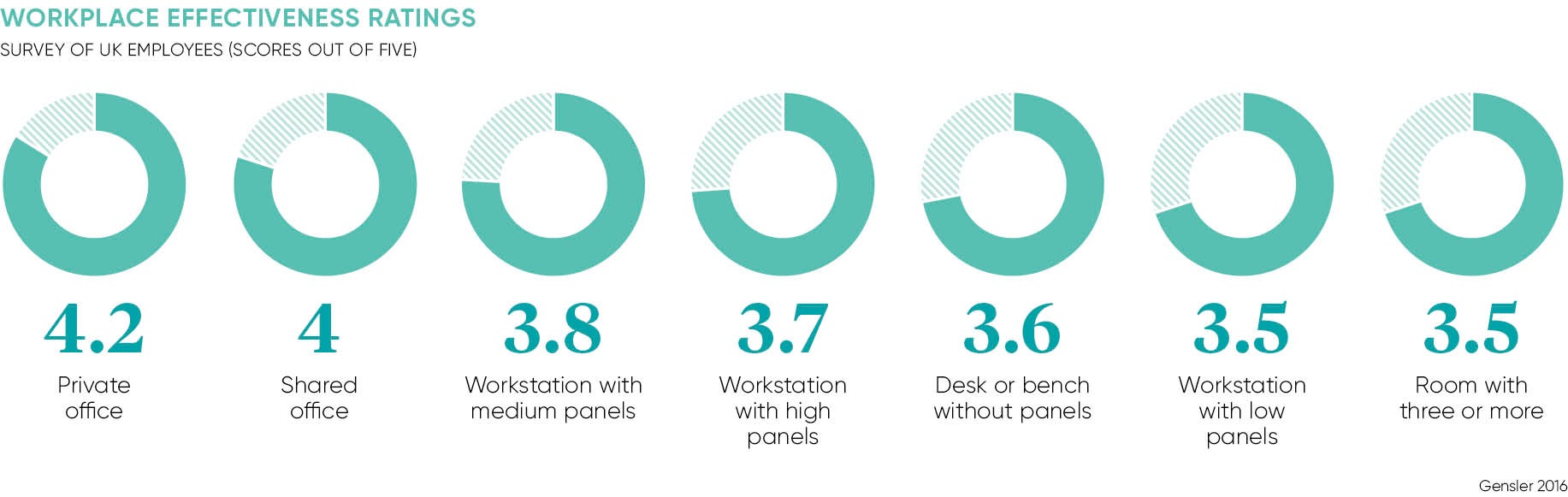

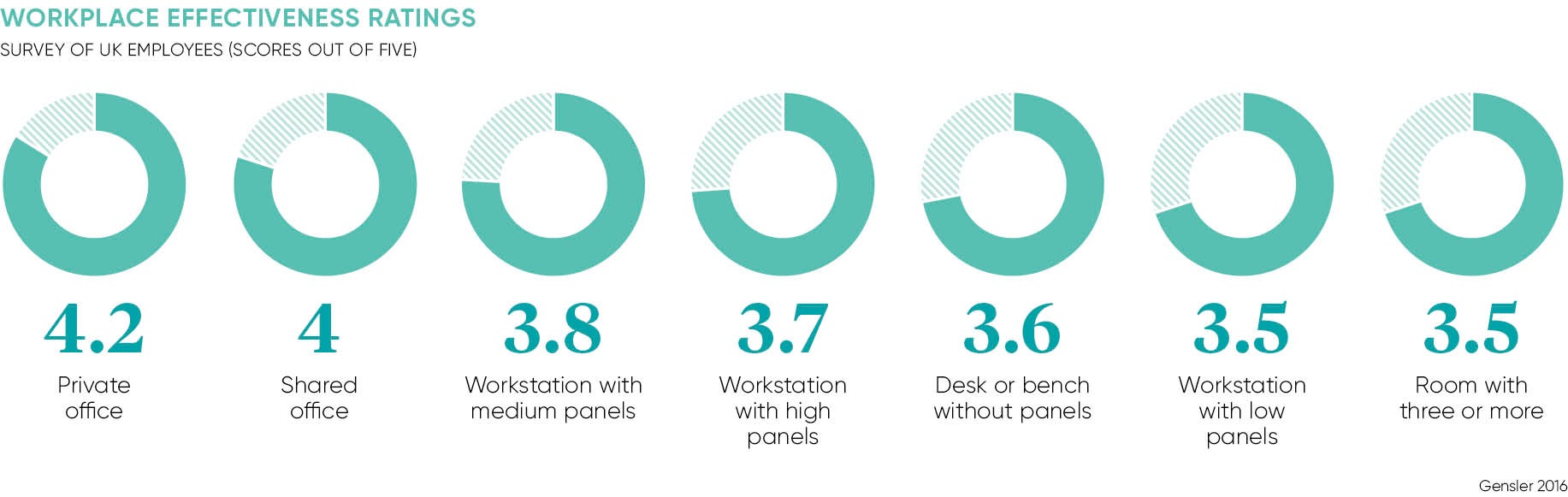

“But what has definitely happened in the UK, and our own research points to this, is that there are ‘haves and have nots’ in the UK working environment and it favours those in managerial positions.”

Indeed, Gensler’s 2016 UK Workplace Survey revealed that those predominantly in management or leadership positions with choice and autonomy of where to work are not only more productive, but innovative as well. However, those employees without choice and autonomy and those fixed at assigned workstation in “impoverished” open-plan workplaces appear to be suffering the most.

But what impact does the open-plan workspace have on the leadership and authority of management? Adopting an open-plan environment removes the obvious demarcation lines that exist in a hierarchical organisation, says Mark Swain, director of partnerships at Henley Business School.

The idea of rank and hierarchy is changing in networked organisations

“Respect for someone more senior is obvious when you’ve got a physical structure of space that demonstrates that,” he says. “I think that open-plan offices blur those rules of rank. If you’re going into a corporate that removes the physical structures of rank such as closed offices and makes the directors eat in the same dining room then it reduces that status of leadership in a flattened structure.

“It also stops people from aspiring to leadership roles as there is no elevated status for leaders or managers. If you’re rank and file in an open-plan office and you see the amount of stress that managers are under without the visible signs of the accoutrements of power, then why would you aspire to that?”

But a bias towards people in managerial positions still exists in an open-plan environment, says Mr Tidd. “There is still an invisible hierarchy where managers have the choice of where they work.”

One aspect of leadership that is enhanced by an open-plan working environment is visibility of the senior leaders, argues John Williams, digital strategy director for the ILM. “The key to that visibility is having the chief executive or CEO on the same floor as employees. Employees then feel that the CEO is more approachable, and they can share their thoughts and collaborate more effectively with leadership.”

What is essentially a social-democratic model of community design can work for a big corporate business, but it’s about having a subtle open-plan environment that reflects a wide variety of settings rather than a crude open-plan design, says Mr Tidd.

“Big corporates are recognising that opening up their environment to a more collaborative and modern environment is more attractive to the next generation of talent,” he says. “Most organisations that we work with are very concerned about their talent constraints. A young workforce wants to work in a welcoming and dynamic work environment.”

Many tooth-and-claw capitalist businesses struggle to shift to the more open, democratic and trusting culture that a social-democratic model of community demands, Mr Myerson concludes. “They are much happier with command and control, supervision and surveillance than empowering people, which takes time and effort, and requires new spaces, collaborative technologies and ways of behaving. But they will have to face the challenge sooner rather than later.”

Corporate co-operation