The UK’s offices host a more diverse workforce than ever before. It is not uncommon to walk into a large open-plan space and see four different generations at work at their desks. Legislation addressing age and disability discrimination in the workplace has removed some of the barriers to people of different abilities. Women have broken through the glass ceiling in many previously male-dominated companies.

Inside our larger urban business districts and corporate campuses, employees from all creeds and corners of the globe contribute to the UK economy as part of the free movement of labour that has been integral to the British workplace for the past 20 years.

A workforce that is essentially a kaleidoscope of such a broad span of different shapes, sizes, abilities and cultural preferences represents a much greater challenge for workplace designers today than in the past. The mid-20th-century office population – the “family-formation workforce” of 21 to 45 year olds, as economists have described it – was overwhelmingly white, able-bodied and male. Today, one size does not fit all.

Not only is the UK’s office workforce more diverse, it is also more demanding and dissatisfied. While physical injuries in the workplace have reduced from a generation ago, mental health problems are now sharply on the rise. Working days lost through stress, anxiety and depression are costing the UK economy more than ever before and contributing to its current productivity crisis.

Not surprisingly, strategies to combat a wellbeing deficit in the workplace are now at the top of the boardroom agenda. And while some of the wellbeing problems that workforces experience can be put down to inappropriate employment policies, inadequate training, insensitive management or unreliable IT systems, the work environment itself is under real scrutiny.

What can workplace designers do to improve the wellbeing of employees?

Research in the field suggests that, whatever the age, gender, ability or culture of the employee, having a sense of control is a key driver of wellbeing and happiness at work. This control takes many forms, control over work-life balance, time, tasks, interactions with others and patterns of commuting, for instance. But it also relates to our immediate surroundings. This is where workplace design comes in.

A sense of control in workplace design is expressed through individual control over physical environmental conditions (heat, light air); choice in terms of different types of workspace to use (not just the standard desk); freedom to reconfigure your workstation (height-adjustable desks are increasingly popular); personalisation (hacking your workspace is a growing refrain); and participation in the design process itself.

All of these trends are now evident in workplace schemes. The rise of the intelligent building, in which new technology will increasingly enable the physical environment to respond automatically to the needs and preferences of the people working inside, holds the promise of giving over more control to employees. However, in the use of sensors to plot movement, sense presence and engineer social interaction, technology also has the potential to cast a big brother shadow over the workplace and reduce wellbeing rather than boost it.

Company engagement

Nevertheless, the opportunity to give employees a direct say in how the workplace is designed is gaining ground. Compared to other areas of the built environment, such as community housing or neighbourhood schemes, co-design techniques have been underutilised in the workplace. That is beginning to change as designers focus more intently on a target described by the leading environmental psychologist Jacqueline Vischer as “psychological comfort”.

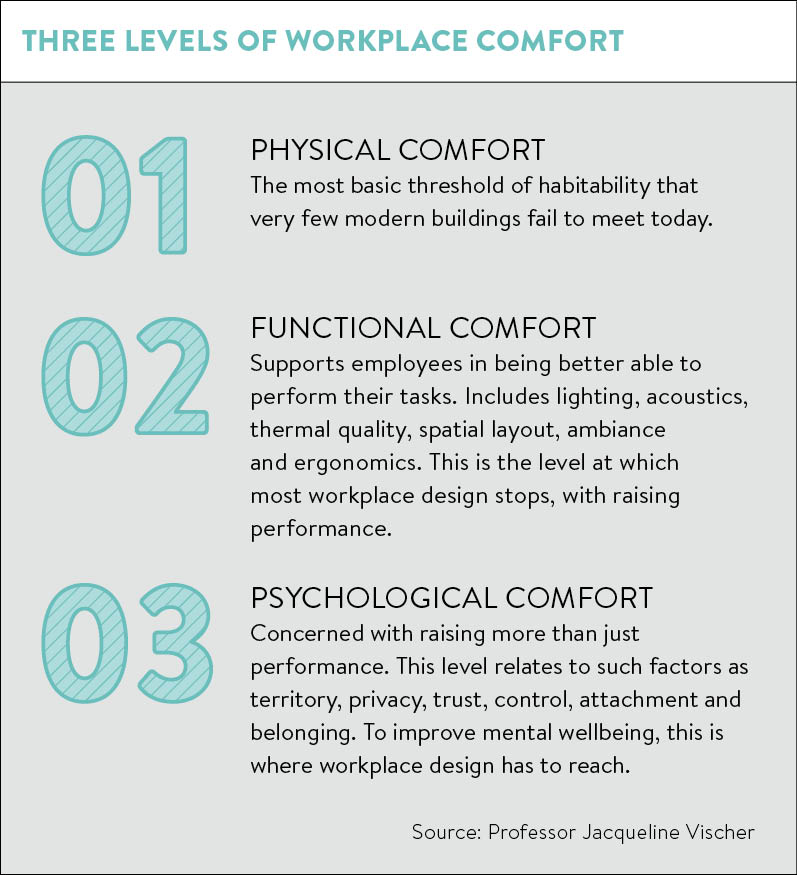

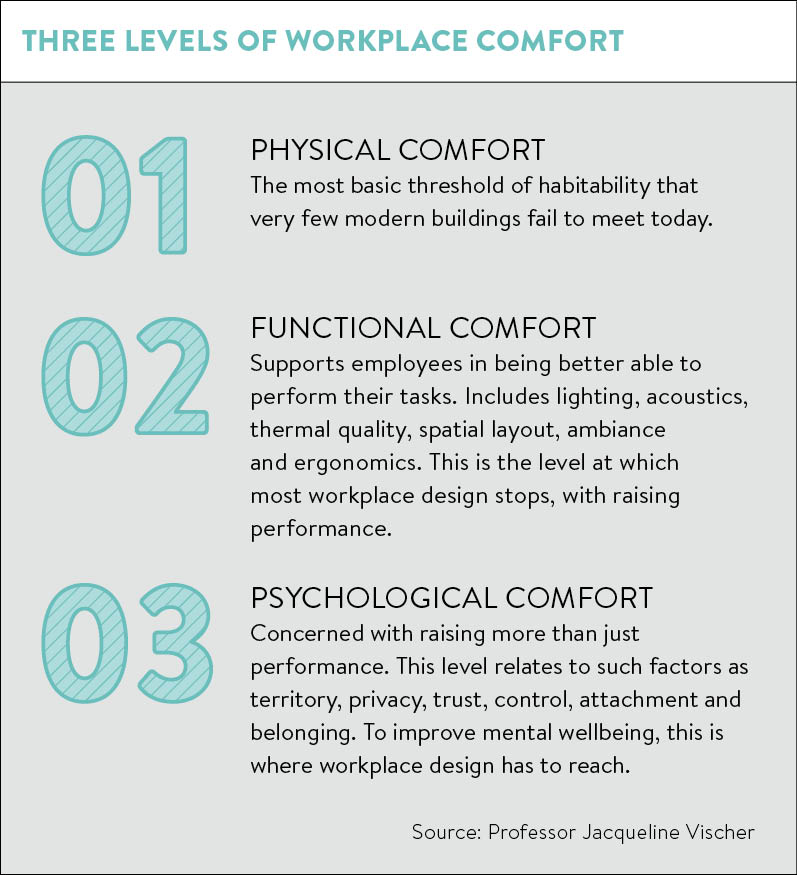

In her work, Professor Vischer has identified three levels of comfort in the workplace. The first is physical comfort or the most basic threshold of habitability that very few modern buildings fail to meet today. The second level is functional comfort, which supports employees in being better able to perform their tasks. Lighting, acoustics, thermal quality, spatial layout, ambiance and ergonomics are all important here. This is the level at which most workplace design stops, with raising performance.

Inclusive design that improves the environment for all is increasingly seen as the way to go rather than providing interventions for any special needs group

But there is a third level, psychological comfort, right at the top of the pyramid of user need that is concerned with raising more than just performance. This level relates to such factors such as territory, privacy, trust, control, attachment and belonging. To improve mental wellbeing, this is where workplace design has to reach.

British researcher and consultant Craig Knight conducted an unusual experiment to test productivity and wellbeing in different environmental conditions. He found that when office workers were empowered to enrich the workspace themselves with plants and photographs, the speed and accuracy of their work improved compared to when the researcher arranged the space on their behalf or provided no visually enrichment at all. When the researcher intervened to disempower them by reorganising their workspace after they had designed it, levels of performance dropped.

Getting to know employees

Dr Knight’s results suggest that, given such a diverse workforce, we need a much better understanding of individual employee’s needs and preferences to redesign the workplace to raise wellbeing. A common approach has been to try to segment the office population by age. Huge attention is currently being given to the behaviour of the millennial cohort, the most recent generation to enter the workplace en masse, and their different attitudes to space and technology. At the other end of the age spectrum, baby boomers with extended working lives due to the pension shortfall also command interest. How can they be engaged?

Evidence suggests that older workers have particular problems with noisy open-plan offices. It is recommended that dedicated spaces to concentrate and recuperate are provided in the workplace. But open-plan distractions and the relentless, exhausting grind of office life under fluorescent glare affect all age groups. Younger people can burn out just as quickly as older workers. Inclusive design that improves the environment for all is increasingly seen as the way to go rather than providing interventions for any special needs group.

Indeed, segmenting the workforce through the lens of age, gender or ability is under challenge. Far better, say the experts, to look at what people actually do at work and how they interact with the building. User typologies are now being more widely deployed in workplace schemes: concepts such as the “anchor” (always in the office at their desk), “connector” (always in the office, but never at their desk) and “navigator” (rarely in the office, always on the road) are seen as more helpful to getting office design right than making traditional assumptions based on sex, seniority or disability.

In a global knowledge economy, despite current political upheavals that might put up new barriers, we will continue to have a diverse workplace operating in a business climate that requires increasing levels of innovation, collaboration and communication. We will need to fix the UK’s productivity gap with other industrial nations. Work is increasingly a social activity and offices will become more convivial and supportive of human interaction. Redesigning the workplace to lift the mental wellbeing and satisfaction of employees is a vital first step along that road.