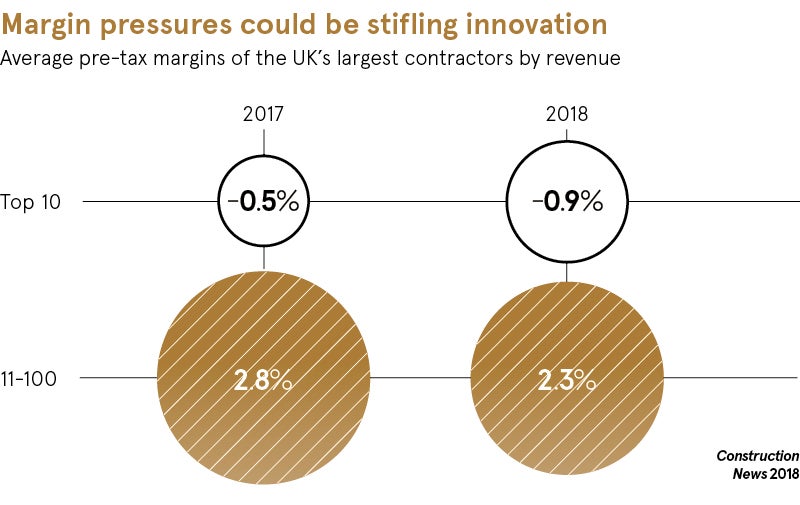

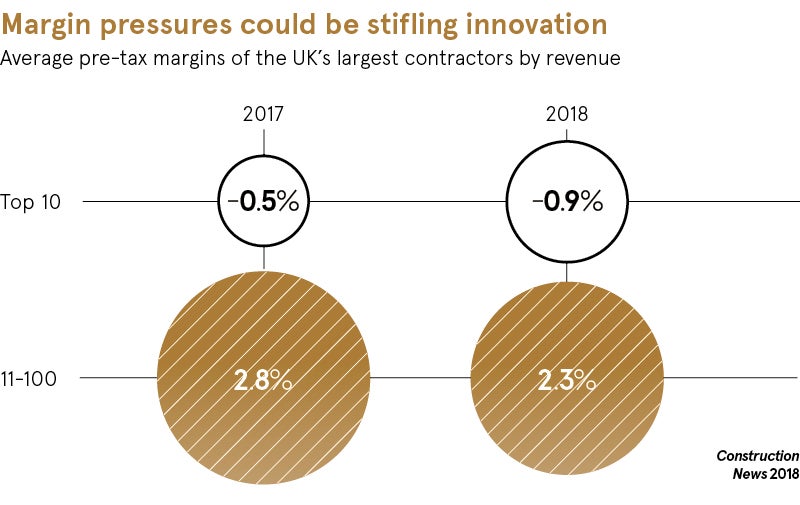

Clients in the construction sector may not appreciate it, but they often get staggeringly good value from their projects. Contractors and sub-contractors, and architects and engineers, are in fierce competition for projects and, as a result, subsist on wafer-thin margins.

According to The Construction Index, the top 100 contractors operate on an average profit margin of just 1.5 per cent. Other assessments are even gloomier.

The professions are leading the adoption of BIM, while the trades need a little more persuasion

The industry has led this hand-to-mouth existence for decades, struggling to keep costs down in the face of inflationary pressures in wages, materials and services. This in tu feeds short-termism in management and procurement. Other industries have faced similar challenges and many have found at least a partial answer in digital technologies. Can digital improve margins and reduce short-termism in construction?

What is BIM?

Many feel the answer lies with building information modelling (BIM). At its heart, this is a digital model of a project, encompassing not just the architectural and structural design, but also layers of information on the surrounding environment and infrastructure, surface finishes, and details such as fixtures and fittings.

BIM promises to eliminate the phenomenon, especially on complex projects, of each specialist working to their own set of drawings and proprietary specifications. BIM can be described as a fusion of old-fashioned computer-aided design with geographic information systems and advanced inventory management. It can even incorporate internet of things capabilities.

Adoption is certainly increasing, boosted by the 2011 UK Government Construction Strategy, which mandated that all centrally procured government projects must include BIM as part of the documentation process by 2016. The technology, in theory at least, improves workflows, increases transparency, and enables problems to be identified and remedied earlier in the process. All this should reduce risk, improve margins and, as a result, tackle the problem of short-termism.

For it to work, though, BIM requires buy-in from across the industry. It is of little benefit if the architect and structural engineer collaborate, but the electrical and heating installers revert to their own systems. Unsurprisingly, the professions are leading the adoption of BIM, while the trades need a little more persuasion.

Lack of understanding holding companies back from embracing BIM

Glen Dimplex, which makes heating systems, recently commissioned independent research showing that almost three quarters of designers and architects are now using visualisation technology in the early stages of project development. The surprise may be that a quarter do not.

Kenny Ingram, global industry director at software vendor IFS, says the pressures on construction are growing and BIM is only part of the answer.

“Industry faces a skills shortage, and must embrace new technologies to deliver projects faster and more economically,” he says. “BIM can help move the industry from document-driven to data-driven, but is so far really only understood by engineers and architects. Its complexity continues to be a source of debate. Companies should understand that BIM is mainly a tool enabling them to move quicker, plan better, be more accountable and execute more efficiently.”

Paul Barton, operations director at BIM vendor Clearbox, says short-termism comes from low margins and addressing this requires fundamental change.

“Construction isn’t geared to an asset life cycle; it just tries to protect its little profits on each aspect of the build. We need clients to invest in early-stage design, visualise the process and bring a collaborative method of delivery. Then the industry won’t have to always force the lowest price.”

The sentiment is echoed by Chris Hamilton, head of digital solutions at engineering firm Jacobs. He says: “BIM it is traditionally implemented at the point where decisions have been taken. Engineers design a solution to a project and then apply BIM, building their datasets to match. But a huge amount of data could be captured and analysed before the decision to design, which could help find better ways to achieve the desired outcome.”

How BIM can work where there were no digital models before

Agreement, then, that BIM is best applied as early in a project as possible. But what about the redevelopment of existing projects, where no digital models have ever existed?

The City of Paris is currently redeveloping a large area around the Eiffel Tower, which has been criticised for being unwelcoming. An early part of the project, timed for completion by the 2024 Olympics, is Autodesk’s creation of a 3D model of the existing site to enable the visualisation and evaluation of proposals and designs.

On a rather less grand scale, engineering consultant Curtins has employed BIM along with inexpensive Google Cardboard VR (virtual reality) headsets as a means of stakeholder engagement on a school development. This enabled pupils, parents and staff to see it in virtual form, and showed that not all applications of digital technology carry significant cost.

Technology alone is not enough for innovation

Even so, resistance remains the Achilles’ heel of BIM. While many in the industry are enthusiastic about it, some remain unconvinced.

Adrian Fowler, managing director of building services provider Midfix, says the government mandate may have had a negative effect on digital uptake.

“It may sound counterintuitive: how can a digital initiative be a barrier? Simply focusing on just one area of digitisation inevitably causes others to suffer. With companies spending so much implementing BIM, there’s little left over for other advances,” he says.

Max Jones, corporates relationship director at Lloyds Bank, observes that barriers remain. “A combination of low margins, inertia and long project life cycles hold innovation back,” he says. “Contractors are embracing technology, but transformation cannot happen overnight. Technology is a part of that, but workforces and cultures must change too.”

Perhaps the biggest obstacle is a sense of déjà vu. Construction’s notorious short-termism is partly because it has witnessed many previous initiatives come and go. It remains to be seen whether BIM will prove any longer lasting.

What is BIM?

Lack of understanding holding companies back from embracing BIM