When Amazon announced in 2013 they were starting to test deliveries by drone, opinion was split between doubters who thought it was nothing more than a gimmick and those who thought that by now the skies would be full of unmanned aircraft delivering goods to homes and businesses.

As in so many areas of technology, perception has moved faster than reality. At the moment drones remain just a gimmick, says Tim Gammons, global smart mobility leader at engineering consultancy Arup. “But you only have to look at how previous gimmicks have developed, such as apps and mobile phones, to see they could become very widespread very soon,” he says.

A reality?

From a technology perspective, the capabilities of drones are improving day by day. Advancements in autonomous piloting, “sense and aware” technologies, and increased battery life mean delivery drones are now very much a potential for the future, says Trish Young, UK head of business consulting for retail, consumer goods, travel and hospitality at Cognizant.

“However, a lot of preparation is still needed before drone delivery in everyday supply chain and logistics becomes feasible,” she says.

While there is huge interest in drones and there have been numerous technological advances in terms of enhancing airborne time, autonomous navigation and lowering operational costs, there are still barriers to wider commercial adoption.

“Given that most commercial drones currently are flown along the line of sight, or can only travel short distances and with light loads, they are only really suited to delivering smaller business-to-consumer packages at the moment,” says Ms Young.

Amazon says it wants to offer a service that will be able to deliver any package that weighs less than 5lb (2.27kg) by drone, to anywhere that is within a ten-mile radius of its depots, within 30 minutes. A Deutsche Bank report says drone delivery would cost just $0.05 per delivery mile compared with $6 to $6.50 for a typical shoebox delivery via logistics groups such as UPS or FedEx.

There is an opportunity for the last-mile delivery of smaller goods and also for deliveries of a critical nature, such as vital components that need to be delivered fast, says Mr Gammons.

An area where the technology could quickly gain traction is healthcare and emergency response, including the delivery of medical emergency services. “One of the main issues for emergency response teams is getting life-saving equipment and treatment to the people who need it as quickly as possible,” Ms Young points out. “As drones become more and more cost effective, the possibilities to reach those most in need are growing exponentially. Drones can deliver small packages to the incident area in densely populated and congested urban locations quickly and accurately.”

Drones are already being used to deliver blood and vaccines to hospitals in Rwanda. Less constructively, if no less inventively, criminals have used drones to deliver drugs to prison inmates.

Improvements to be made

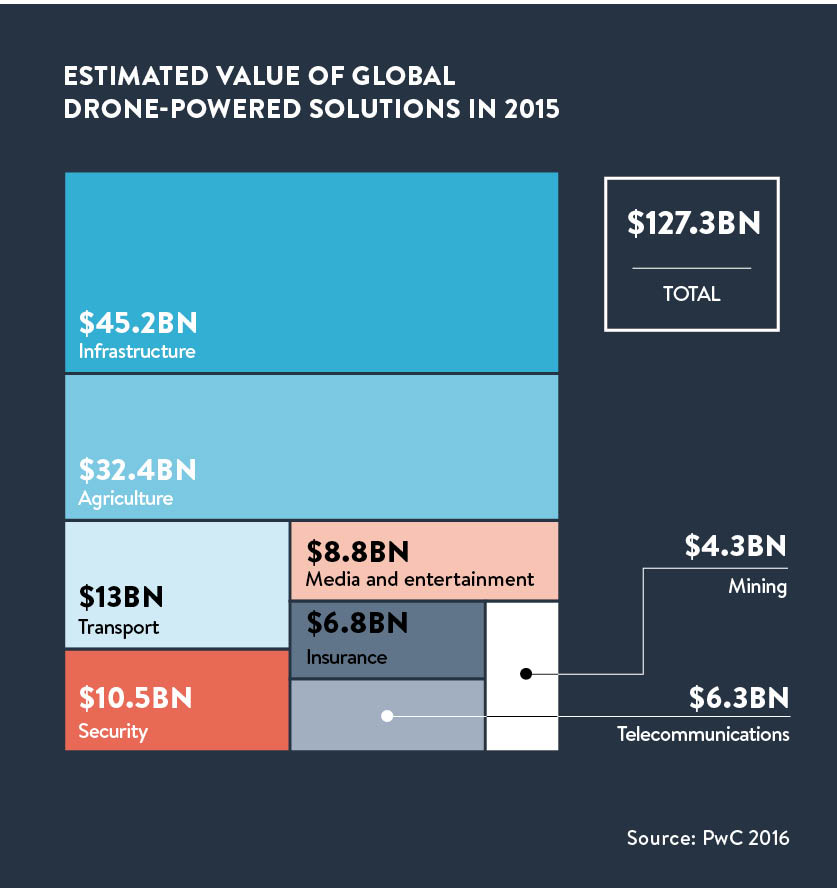

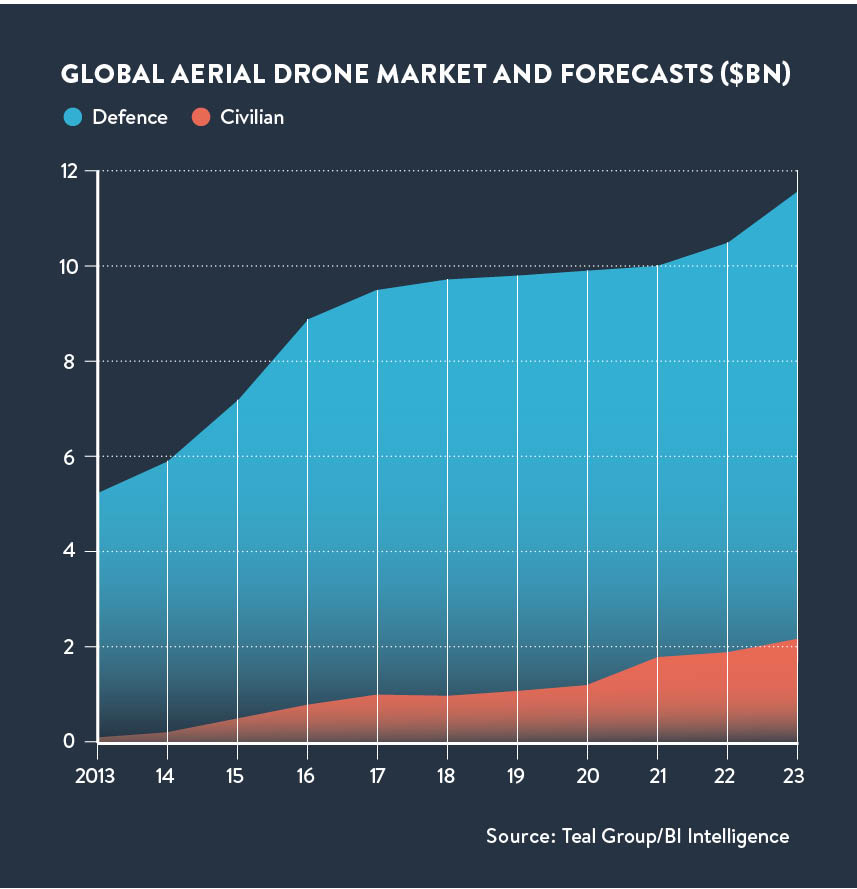

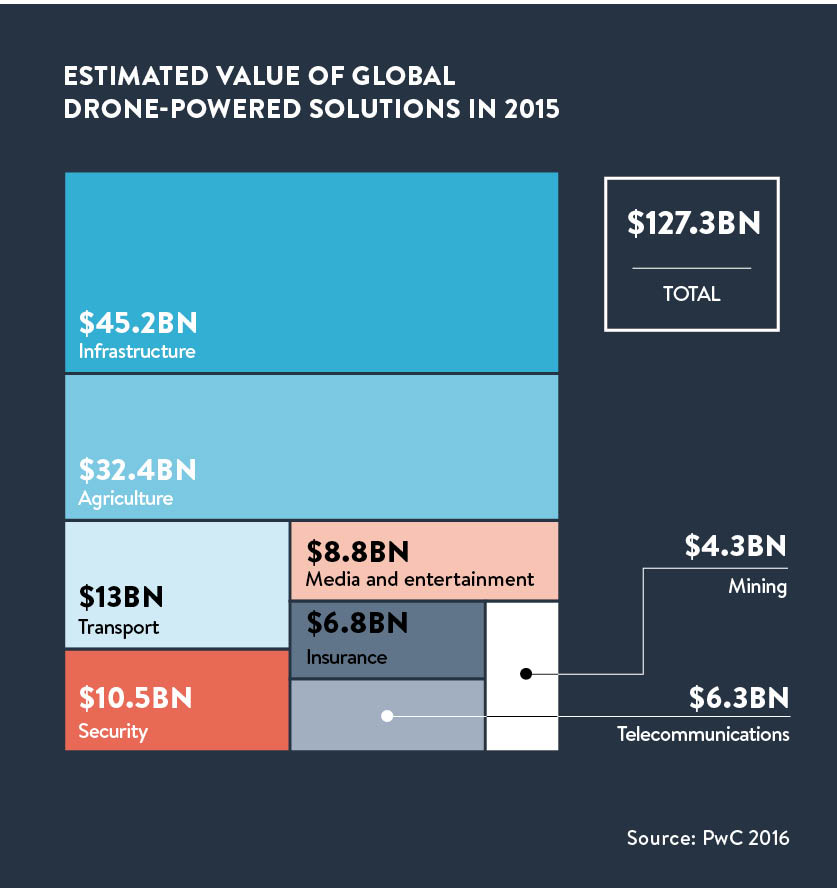

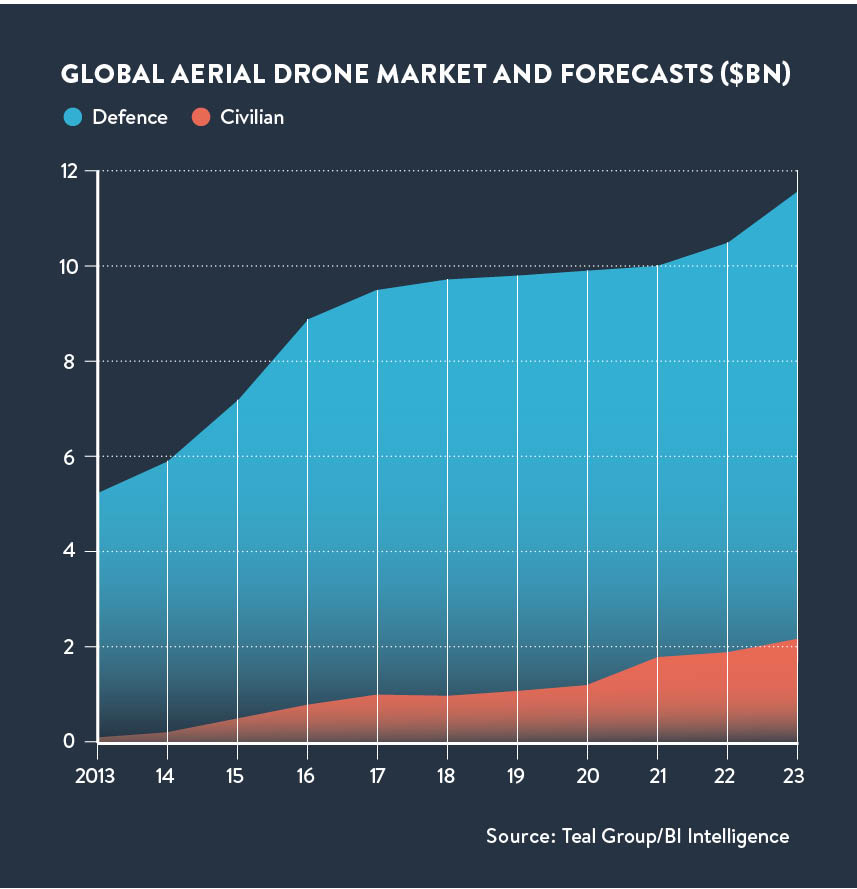

Despite some stumbling blocks, the market for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as drones are technically called, is projected to reach $5.59 billion by 2020. “Once the technology is developed further, drones could potentially speed up and reduce costs associated with traditional supply chains, deliver an additional source of data gathering and provide added convenience because they are not restricted to postcodes,” Ms Young says.

But before drones will be able to sustain the volume and consistency of business-to-business services, more work needs to be done to increase their load-lifting capacity and journey endurance.

In the long run, retailers and companies in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector will be heavy users of UAVs, Ms Young predicts. “In the retail and FMCG space, drones are fast becoming a viable platform for delivery of products to customers. Retailers such as Amazon and Walmart have already begun trialing drone projects after realising their potential role in the future of logistics.”

There are even plans for drone ships. Rolls-Royce has recently published a white paper proposing autonomous, remote-controlled ships with no people at all on board, which it says would cut costs and provide more room for cargo.

But Ms Young cautions that for drones to really take off in transportation, a number of issues still need to be addressed in local markets such as airspace management, liability and privacy-related issues.

Legislation and policy frameworks

In addition, to make the optimistic expectations a reality, governments will have to relax some of the current restrictions, perhaps set up a register of companies allowed to operate drones, and organisations will need to prove they have a strategy in place that complies with legislation.

“We will need concrete legislation that outlines parameters of how they can be used. Only once an enabling policy framework is in place can the drone market fully develop,” Ms Young says.

The UK already has guidelines around the use of drones. The Civil Aviation Authority’s Drone Code requires drones to be flown in direct visual line of sight of the pilot; away from congested areas, aircrafts and airports; at least 50m from people, vehicles and structures; and under 400ft.

In the United States, drones can be used to inspect crops and infrastructure such as bridges, for aerial photography and for search and rescue purposes, but the US has placed restrictions on their use for deliveries.

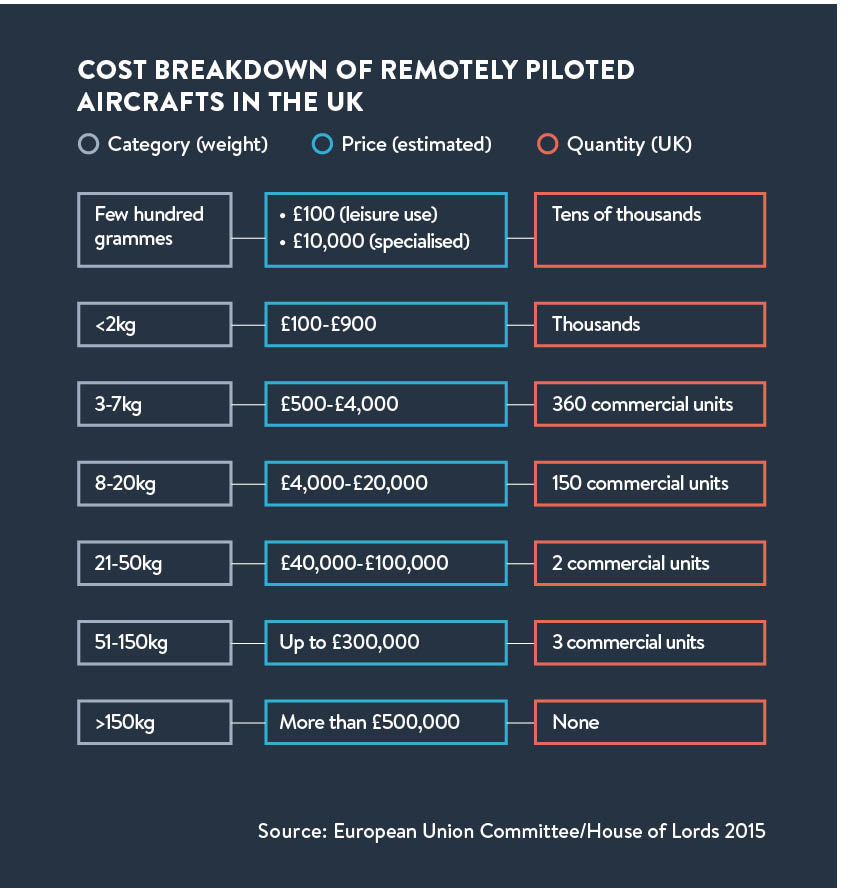

The US Federal Aviation Administration has stipulated that the drone and its payload must weigh less than 55lb combined (about 25kg), that it must be within sight of its pilot, and each drone must have its own pilot, while those flying drones must pass a test every two years.

In the UK, the Civil Aviation Authority says deliveries must weigh no more than 20kg. So while companies such as Amazon and DHL say the technology is ready to be rolled out on a commercial scale, comprehensive restrictions imposed by regulators are putting a brake on the sector’s development and frustrating companies that want to try something new.

But there are good reasons for this caution on the part of the authorities. Most obviously, it is still not clear how drones will interact with the world around them, who is responsible if there is an accident and how users can ensure the devices are safe.

One of the biggest issues is cyber security because drones need a wireless connection to an operations centre, making them vulnerable to attack by hackers. The answer to this is to implement encryption technology, but it is difficult to do this well, says Cesar Cerrudo, chief technology officer of cyber security consultancy IOActive.

“Drones rely a lot on GPS technology, and it has been proven that you can jam the signal and cause interference so drones don’t know where they are,” he says. “Another risk is that an attacker takes over your operations centre and then he will have control over all your drones. The best approach is to make sure your operations are strongly encrypted, not just on paper, but when your plans are implemented.”

But Mr Cerrudo questions the extent to which this will happen because it requires investment and time that many companies are not prepared to commit. Nor does he think that, just because drones have emerged at a time of growing awareness of cyber threats, the industry will deal with the issue any better than other sectors.

“Tech companies have been investing in cyber security since the late-1990s, but experience tells us that every time there is a new technology, it has all the same problems that the old technologies did,” he says.

Nonetheless, sooner or later drones look like being the next disruptive technology within the supply chain and logistics, and companies would do well to start investigating strategies now to see if drones would lift their business model.

A reality?

Improvements to be made