Imagine two new patients in an accident and emergency (A&E) department. The first is kept waiting for three hours fifty-nine minutes; the second for four hours one minute. Would the most critical patient be treated first?

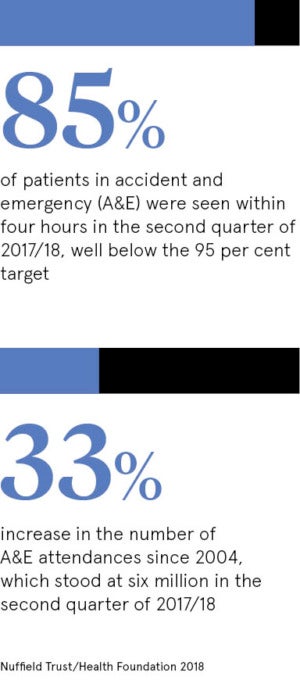

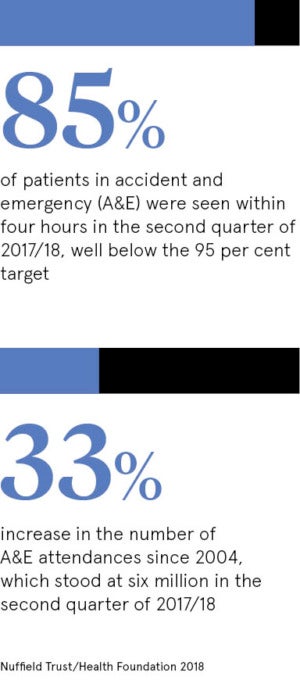

You would assume so. But A&E departments are financially penalised for breaching targets. They must make clinical decisions about 95 per cent of emergency patients within four hours; for example, by deciding whether to admit or discharge them.

Once a patient breaches the target, by waiting more than four hours, the system gives busy emergency departments a perverse incentive to focus on patients who have not breached it.

This is said to distort clinical priorities and to be a classic example of a system which puts too much emphasis on target or volume-based care and not enough on value-based care. Volume-based healthcare provides measures which evaluate care according to numbers of patients treated and treatments administered.

This is said to distort clinical priorities and to be a classic example of a system which puts too much emphasis on target or volume-based care and not enough on value-based care. Volume-based healthcare provides measures which evaluate care according to numbers of patients treated and treatments administered.

The value-based model, which puts the overall needs of both the individual and overall populations at the centre of the picture, has evolved out of a global collaboration led in the UK by Professor Sir Muir Gray, a humorous Glaswegian once described by a former chief medical officer as “one of the most creative minds in British medicine”, and in the United States by Professor Michael Porter of the Harvard Business School. Co-author with Elizabeth Teisberg of the prize-winning Redefining Healthcare, Professor Porter also wrote a pivotal paper in The New England Journal of Medicine calling for a switch from volume-based to value-based care.

The term value-based care has created confusion, not least among healthcare professionals. Some have dismissed it as a trendy new phrase or management gobbledygook. But ever-increasing numbers of doctors believe that it could be as important to healthcare as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates have been to computing. Sir Muir says: “It will be as critical as evidence-based medicine.”

He and his distinguished Harvard colleague are united in their concern that ignorance is perhaps healthcare’s biggest challenge.

Sir Muir, who helped to create NHS Choices and the National Library for Health, explains: “What is the right level of prescribing of antidepressants in any given area? We just don’t know.”

A report by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, Protecting resource, promoting value: A doctor’s guide to cutting waste in clinical care, says: “Estimates suggest that around 20 per cent of mainstream clinical practice brings no benefit to the patient as there is widespread overuse of tests and interventions.”

While Sir Muir’s main focus has been populations, Professor Porter’s has been individual patients. According to his report in The New England Journal of Medicine: “Value in healthcare remains largely unmeasured and misunderstood.”

Is this really true? Are we failing at this most basic level, even though global health spending is projected to reach nearly $9 trillion by 2020 compared with $7 trillion in 2015?

Dr Rupert Dunbar-Rees says a big challenge for value-based care is persuading healthcare professionals that they can identify relevant outcomes from patients

Dr Rupert Dunbar-Rees, a former NHS GP, and founder and chief executive of Outcomes Based Healthcare, says: “We are very good at spending money on doing things, at operating on people and prescribing tablets. But we are quite weak at knowing whether it has made any difference whatsoever. Has it really impacted someone’s life? Is their quality of life better? Is their mobility better? Their pain?”

Political correctness and consumerism is said to have consigned old-style paternalism to the sidelines and made ‘patient power’ the new war cry

These are critical questions for both patients and clinicians. One of the defining trends of modern healthcare has been the growing involvement of patients in their own wellbeing. With the spread of healthcare information via the internet, the emergence of powerful patient advocacy groups and general awareness of healthy living, the patient has ceased to be just a passive recipient. Political correctness and consumerism is said to have consigned old-style paternalism to the sidelines and made “patient power” the new war cry.

But how much power do patients actually have? What is happening now suggests that patient power has been extremely limited, for example to changes in emphasis in individual relationships between doctors and patients. They are now perhaps more likely to decide together what to do for the best.

In contrast, value-based healthcare is potentially far more radical. It is putting the patient at the forefront of the healthcare planning process. UK patients have been working alongside healthcare professionals to determine the outcomes they want from their own healthcare. Positive outcomes are defined as any change for the better in a patient’s health, such as being able to walk again after a bad fall or feeling in control again after a bout of mental illness.

In one innovative programme, Camden Clinical Commissioning Group (CCCG), in north London, ran an “outcomes party” for 55 elderly patients, relatives, clinicians and volunteer organisations. This established that their top priority, especially among patients and families, was time spent at home and not in hospital.

Reporting in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr Caroline Sayer, then CCCG chair, says: “When they told us, ‘time spent at home’, we designed care with that patient-defined goal in mind. Focusing on a single, clearly understood goal, defined by patients and embraced by all involved in their care, created powerful clarity of purpose across a complex range of providers and organisations. Our experience shows the potential for a patient-defined outcome to drive the collaboration needed to integrate care.”

Integrated care is a hallmark of the value-based model. The tragic case of Julia shows why. Writing in Heart BMJ, Dr Dunbar-Rees and colleagues reported that Julia had suffered from high blood pressure, heart failure and a heart rhythm abnormality, which increased her risk of stroke. She then had a stroke. While in hospital she was also diagnosed with chronic kidney disease.

Incredibly, within just one year, she had more than 80 appointments with consultants, specialist nurses and other healthcare workers. But she felt progressively unwell. Due to lack of co-ordination or single clear responsibility for her overall care, it was not picked up until Julia eventually visited her GP a year later that she had late-stage lung cancer.

Heart BMJ comments: “If Julia had received integrated care with her at the centre, rather than care in silos, it is much more likely that her diagnosis of lung cancer would have been made earlier and might not have been fatal. Her experience of care would also have been better.”

Dr Dunbar-Rees says one of the big challenges for value-based care is persuading healthcare professionals that they can identify relevant outcomes from patients. “They say that it’s all too abstract or nebulous to use as the basis for commissioning a service,” he says.

“Designing a service to deliver 250 hip or knee replacements each year is a far more concrete task than designing a service to restore people’s mobility, independence and confidence. But experience shows that the latter can be achieved by identifying groups of people with similar needs.” This was the basis of the Camden success.

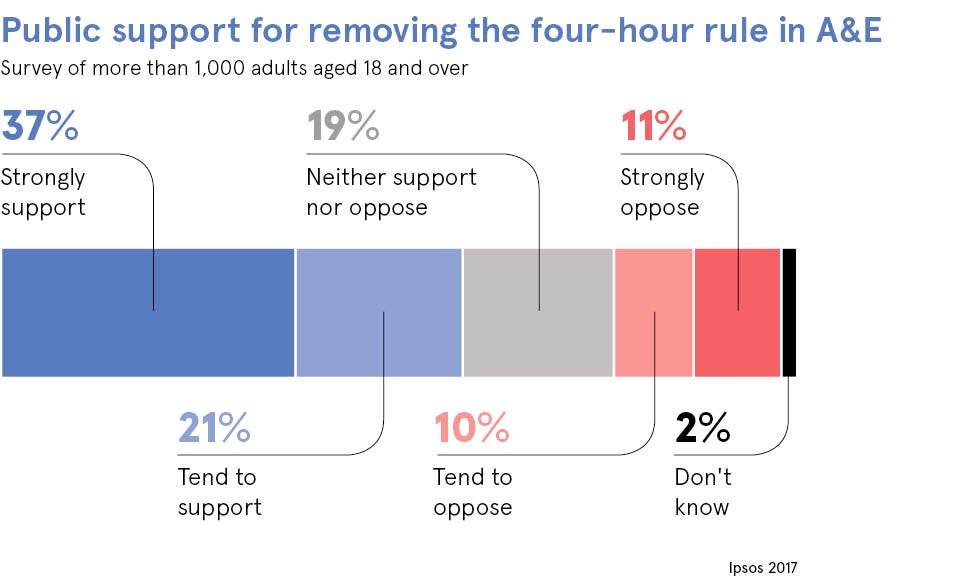

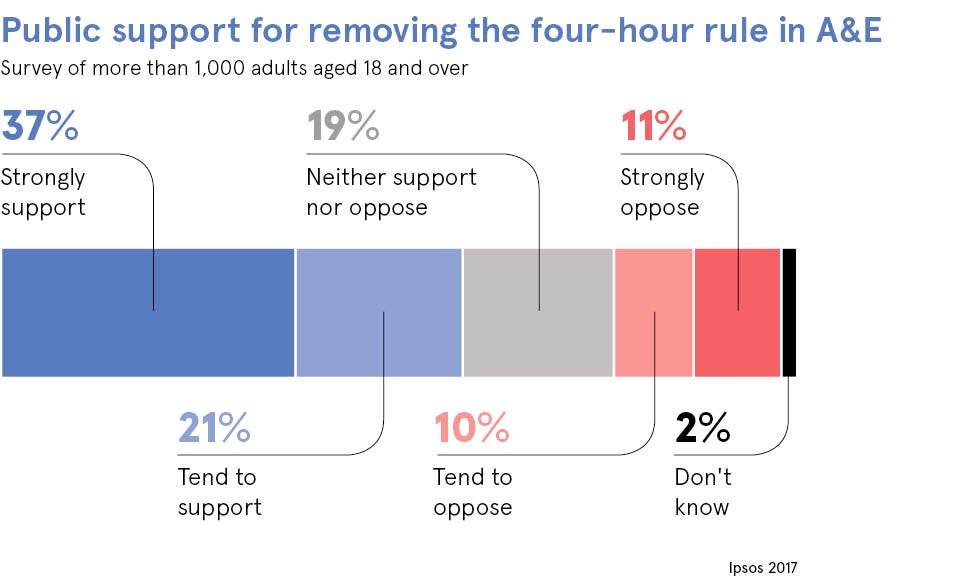

What of the future of volume and target-based care? Targets will continue to hold people to account and measure progress, but value-based healthcare holds the promise of a more sensitive approach towards health policy planning. The four-hour rule is at best a blunt instrument, a finger-in-the-air measurement of a highly complex system, but it has its place.