The more you have, the less you are likely to give away – or so the old saying goes. But that doesn’t necessarily apply to high-net-worth (HNW) individuals, who donate a considerable proportion of their wealth.

The more you have, the less you are likely to give away – or so the old saying goes. But that doesn’t necessarily apply to high-net-worth (HNW) individuals, who donate a considerable proportion of their wealth.

Data from wealth management specialist consultancy Scorpio Partnership shows that overall philanthropy has been fairly static over the past decade, but there has been a growth in strategic and venture philanthropy.

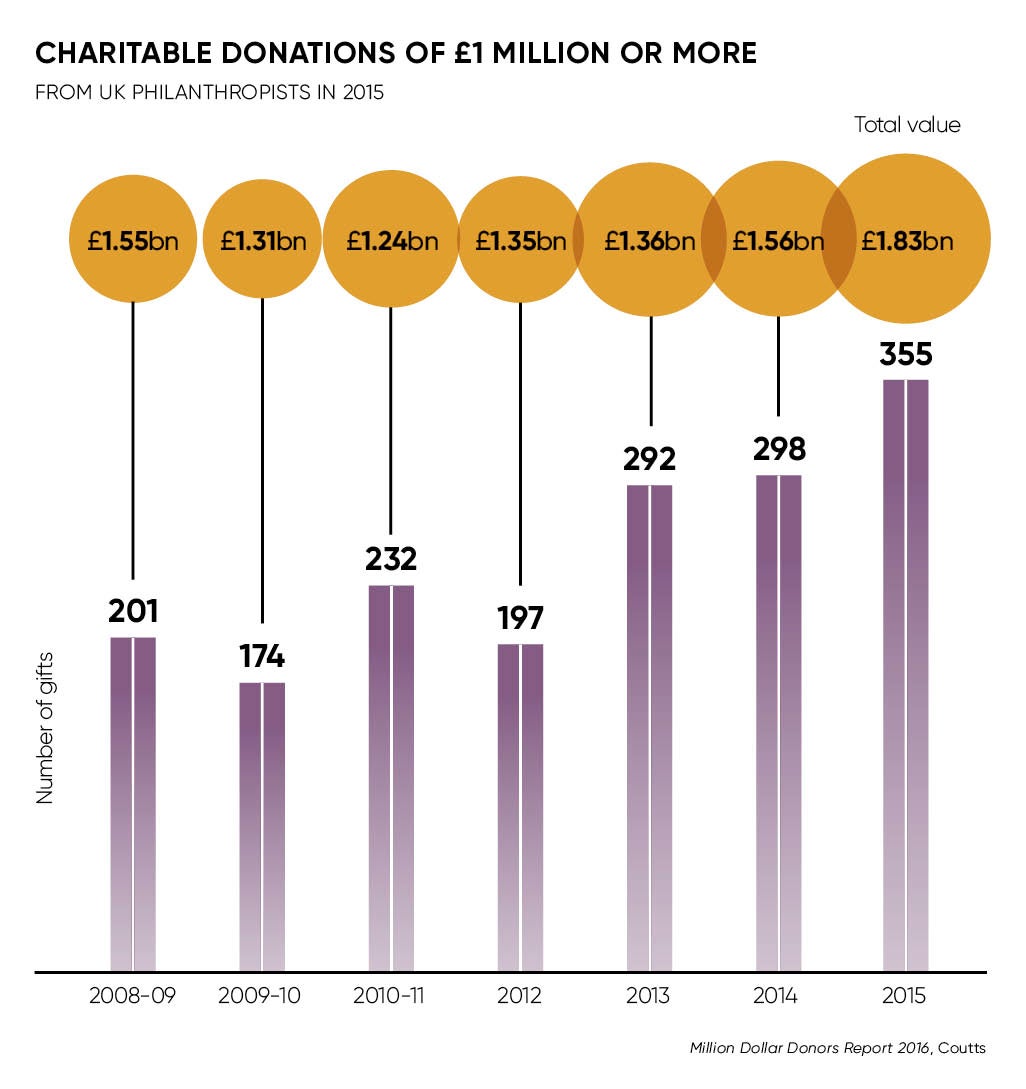

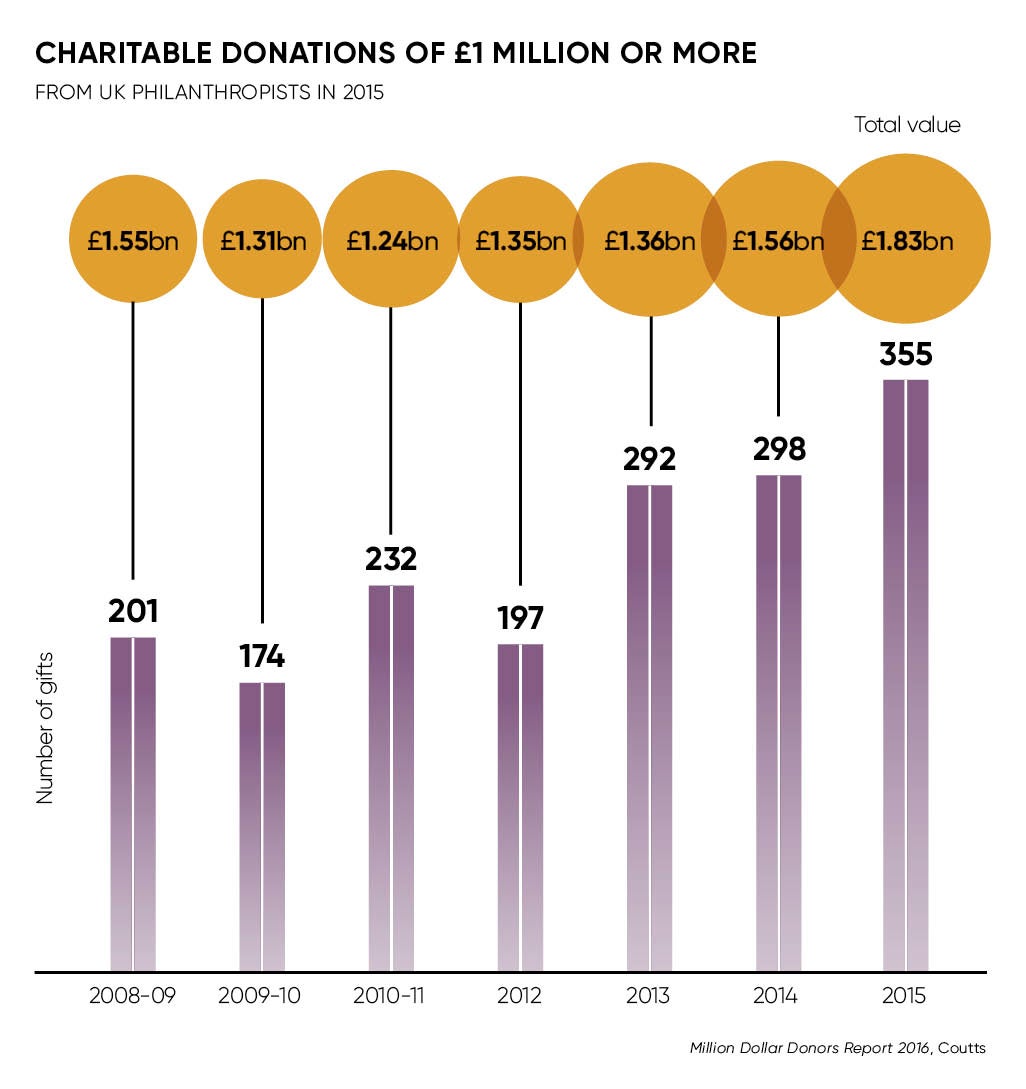

In 2015, 2,197 donations worth $56 billion were made across the UK, US and Middle East, according to the Coutts Million Dollar Donors Report 2016.

The report, which tracks donations of more than £1 million in the UK and $1 million internationally from individuals, foundations and corporations, showed the amount donated more than trebled, up from $17 billion in 2014, while the number of donations increased by 57 per cent.

In the UK alone, there were more than 355 million donations in 2015, worth a record £1.83 billion.

More to managing wealth

There has been a growing realisation among HNW individuals that there’s more to managing wealth than salting away cash into tax-efficient structures, says Rachel Harrington, a director at the Coutts Institute. There are challenges about succession and how to communicate the effect of wealth to the next generation.

However, legacies are not just money released from the cold dead hands of the older generation. There is an interest in what Ms Harrington calls “giving while living”, usually by younger entrepreneurs who have amassed wealth quickly from business ventures.

It is these entrepreneurs and their wealthy families who no longer consider charitable giving enough and have driven a good deal of the move towards philanthropic investment, says Jon Needham, group head of fiduciary services at Kleinwort Hambros.

“They don’t find it particularly rewarding and are concerned by a lack of transparency where their money goes and how much is spent on charitable purposes,” says Mr Needham.

Recent research from Scorpio Partnership shows 26 per cent of UK HNWs choose investment that will achieve both social and financial impact.

Younger investors make up 36 per cent of this number of wealthier individuals who want to see specific objectives achieved by donating money.

Post-financial crisis

The demand for greater transparency and accountability – watchwords of the post-financial crisis fallout – has very much influenced philanthropic investing.

This is why more strategic strategies – social and impact investment – became so popular after 2008. These are designed to not only do good, by achieving a specific objective in terms of environmental or social policy, but also deliver a positive financial return.

However, Gina Miller, founder and chairwoman of the True and Fair Foundation, is highly sceptical of the achievements of social investment, which in part is a function of the industry’s response to demand for philanthropy.

Every wealth manager and private bank now has a philanthropy adviser, she says, because it has become fashionable, like concierge services once were.

“The problem is that advisers are not often trained in philanthropy and money gets given to fashionable charities, rather than matching an individual’s money to charities they would like to invest in,” says Ms Miller.

Although philanthropy is flavour of the month, the wealth management industry has failed to realise the potential demand for this investment approach, according to Scorpio Partnership’s data.

The difficulty of measuring the effects of charitable donation may be a key driver for individuals seeking to become involved with the organisations to which they donate

Only 2 per cent of UK HNWs use their wealth manager for advice on social investment and much of it is done on a DIY basis, making use of standard investments with ethical parameters (20 per cent) or investing in for-profit businesses that have a stated sustainability focus (14 per cent).

Investment houses are responding to a greater demand for so-called ESG funds, those with environmental, social and governance considerations, as there is growing consensus that this approach is less about wearing sandals than demanding high levels of corporate governance and due diligence.

Though wealth managers are also responding to client demand, they face two problems, says Catherine Tillotson, managing partner at Scorpio Partnership.

“First, it is difficult to anticipate how much impact different strategies will generate, especially ESG strategies. And it is hard for them to analyse financial and social returns in parallel, which has led to this misconception of a ‘trade off’. Positioning these products authoritatively with clients remains a challenge,” she says.

The difficulty of measuring the effects of charitable donation may be a key driver for individuals seeking to become involved with the organisations to which they donate.

Challenges

Though some don’t want to be hands-on, seeing entrepreneurs mucking in is simply a reflection of their business world.

They want to not only give money, but also offer advice and time to an organisation, as they would with any company they invested in. They believe they have the skills to improve the operational efficiency of the charity they wish to support.

“It’s part of their DNA and why they are entrepreneurs in the first place,” says Mr Needham.

This engagement offers them the greater transparency about how a charity is run and how it may be helped, and the process of doing that is often the true reward for those investing.

Though donors are demanding a transparent investment experience, the bottom line may be less important than the growth of social and impact investing would suggest.

Their reward won’t be accounted in the column of a spreadsheet, but says Mr Needham, is equally “tangible” and comes from doing something that puts others first.

More to managing wealth

Post-financial crisis