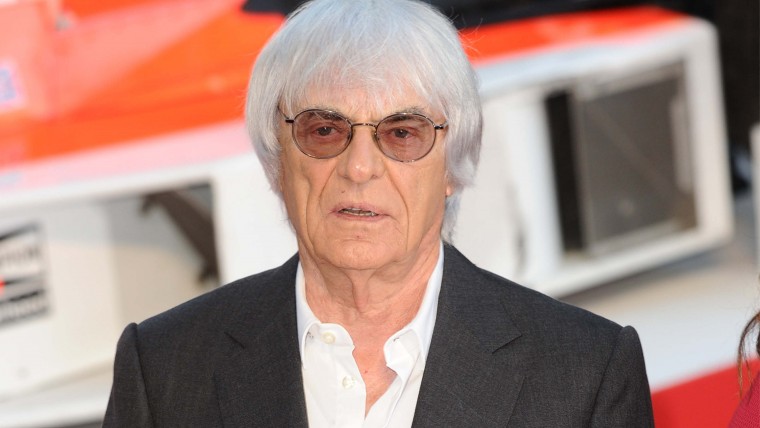

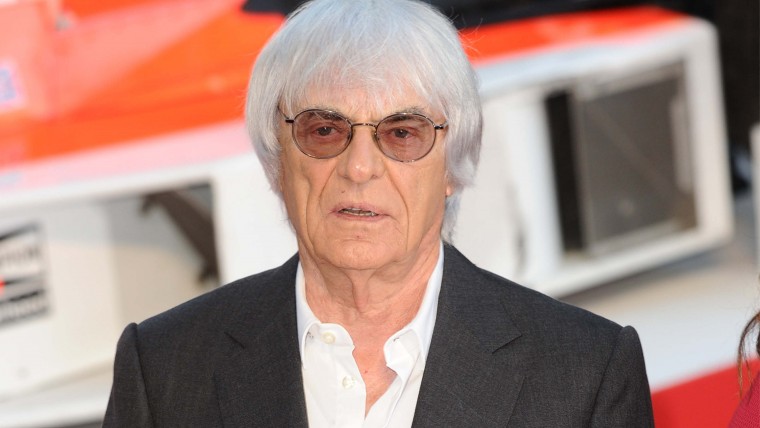

With his round glasses and Andy Warhol haircut, the diminutive figure of Bernie Ecclestone is easy to spot. He has been running Formula 1 since 1978 and almost four decades down the track remains in the thick of the action.

“Every day is a new challenge,” he says in his usual softly spoken tone. “Something happens so you have to keep your eyes open. It’s normal. Running a business is a challenge so that’s how it is.” Ecclestone has had plenty of experience.

The son of a trawlerman, he epitomises the tale of rags to riches. Despite turning 84 last year, he works nine to six, five days a week and says he has been this driven since his youth when he was a trader on London’s famous Petticoat Lane market.

“I’ve always been a bit of a dealer,” he says. “When I was a kid, I used to buy and sell fountain pens. I used to work on Petticoat Lane buying and selling.” When Ecclestone was at school, during the war years, he saw an opportunity to make money from the rations of cakes on sale at the bakery. He bought as many as he could and took them to school in a case so that they could be sold for a profit at lunch time. He soon moved on to bigger things.

Leaving formal education at 16, he established one of the UK’s biggest car dealerships while dabbling in driving. “I made my first million in the used-car business. The precise moment doesn’t stick in my mind as it was just a few more zeroes in the bank account,” he says without a flinch of his famous poker face.

In 1958 Ecclestone entered two F1 races, but gave up when he failed to qualify on both occasions. He had his eye on a grander prize. In 1972 he bought the Brabham team and, although his driver Nelson Piquet won the world championship twice, it wasn’t sporting success that Ecclestone was after.

Owning Brabham gave him a voice at the table when the teams were negotiating a share of F1’s spoils, but he soon found that it was not enough. At the time, F1 races ran as ad hoc, almost amateur, events. Each team made separate deals with each event promoter and television coverage was sporadic since races could be cancelled at the last moment if there were not enough cars to fill the grid.

Ecclestone seized the opportunity to change this. To benefit Brabham and F1 overall, in 1981 he convinced the teams to sign a contract, called the Concorde Agreement, committing them to race at every grand prix. He took this contract to TV companies who could then guarantee coverage. Although the teams controlled F1’s rights, Ecclestone’s company Formula One Promotions and Administration (FOPA) negotiated the deals for them and took a share of the proceeds. The remainder went to the teams and F1’s governing body, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA).

Bambino Holdings, the Ecclestone family trust, has made an estimated $4.1 billion from F1

By 1995 Ecclestone’s salary of £58 million made him the world’s highest-paid executive and at the end of the year his company bought the rights to F1 from the FIA. It handed him the keys to the billionaire’s club.

Bambino Holdings, the Ecclestone family trust, has made an estimated $4.1 billion from F1 and now owns 8.4 per cent with 5.2 per cent in Ecclestone’s hands. The F1 board is controlled by the private equity firm CVC, but Ecclestone still holds all the best cards.

[embed_related]

Unlike many other sports, F1 doesn’t have armies of decision-makers. There is no chief marketing officer, no chief operating officer and no deputy chief executive. “I’m not stepping down or getting a deputy,” he says.

All the key commercial decisions in the sport are still under Ecclestone’s control and this has enabled F1 to act like a speedster rather than a juggernaut run by committee. If he wants to develop a new market, he has the power to sign up a new race. To boost the bottom line he signs up new sponsors.

He is skilled in steering discussions to subjects which suit him. Disarmingly, many of his responses begin with “I don’t know”, often resulting in the questioner offering their opinion instead. When meetings aren’t going in his favour, he has been known to call one person outside for a private discussion, making the person who is being called outside feel special, while tongues wag inside the meeting as to what is going on.

It seems to come naturally to Ecclestone, known as “Mr E” to his staff, but some is by design. F1 is one of the world’s most secretive sports. Its key companies are located offshore, it doesn’t have a PR department and, until recently, the telephone number of its London headquarters was ex-directory.

Two of his favourite characters are long gone: superstar drivers Ayrton Senna and James Hunt. “If you took everything into account, you would have to say that Senna was the most complete driver because he managed to keep with a winning team for longer than anybody. James, I suppose, was my favourite character.”

All key commercial decisions are made by Ecclestone

Ecclestone comes from the classic entrepreneur mould so post-it notes are used instead of technology and he still swears by fax. E-mails come in the form of scanned fax page attachments. He doesn’t have a bodyguard and doesn’t live in a palatial home, but instead has a modestly sized penthouse flat on the top floor of F1’s ten-storey headquarters opposite London’s Hyde Park.

To an octogenarian the internet may seem like a fad, so F1 has adopted a prudent online strategy, avoiding diluting its exclusivity to broadcasters. In turn the business has benefited from buoyant TV rights fees and Ecclestone is reluctant to risk that by making a significant commitment to digital expansion.

“People talk about social media, and what it is going to do and what it isn’t going to do. I haven’t seen that it has done anything for Formula 1 at the moment,” he says. “You will never be able to monitor it. Things come and go – fads.”

Ecclestone’s age gives him visibility shared by few others in business or sport. But the real reason he is still in the driving seat is he has steered $8.6 billion in cash and remaining value to CVC from F1. It’s little wonder that they want to stick around.

“The trouble is that they don’t want to sell. That’s the important thing,” says Ecclestone. “The business of these people is buying and selling companies, and I suppose, if somebody comes wandering in with a big enough cheque book, they will sell. Who knows if I will be one of the buyers?” As ever with Ecclestone, it has an air of mystery because only he really knows the answer to the question.