When businesses used to plan for the future in the days before social media, they focused on building their brand rather than worrying about their reputation. While the board saw investing in the brand through advertising and sponsorship as a long-term strategic goal, it tended to regard reputational issues as a short-term worry that could be sorted out tactically.

But this idea that brand and reputation should be treated separately looks outmoded in the age of social networking and the non-stop news cycle. Now information is shared more easily, crises blow up faster, there is greater pressure for transparency, and customers and clients are increasingly likely to turn to their peers on social platforms to judge the reputation of a company, rather than just listen to one-way brand messages.

BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 and the supermarket chain Tesco’s £263-million accounting scandal in 2014 are just two examples of how a reputational problem ceased to be a short-term issue and had a long-term impact on the brand as profits and the share price slumped.

In both cases, it became clear that the immediate public relations crisis raised deeper questions about senior management’s long-term behaviour that had created the circumstances for these problems to escalate, be it a weak approach to safety at BP or a hard-nosed approach to suppliers at Tesco. BP’s share price halved in the immediate aftermath of the 2010 disaster as claims for damages mounted and, five years later, it remains around 25 per cent lower. Tesco’s stock price also nearly halved as the accounting woes had followed a loss of market share.

Experts say this shows that brand and reputation have become far more interlinked, particularly because of the growing power of platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to magnify a reputation crisis.

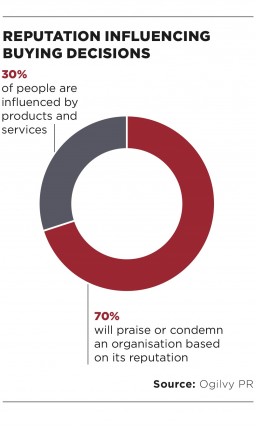

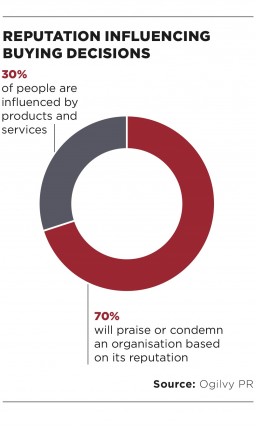

Michael Frohlich, UK chief executive of the agency Ogilvy Public Relations, says: “Reputation is built on three things – what you say, what you do and what others say about you when you’re not in the room. A challenge to the first two will affect, to a lesser or greater extent, the third one. This is where the reputational damage sits, particularly on social media. If a company has a bad product or their chief executive breaks his or her promise, anyone can simply and directly take their issues to shareholders and customers.”

Tim Burt, managing partner at StockWell, a strategic communications agency, agrees that social media has been a game-changer. “All companies suffer setbacks. It’s part of doing business,” he says. “What separates a setback from a crisis is loss of control, whether real or imagined. A social media firestorm – its speed, its intensity – makes any crisis harder to control. When that happens, investor confidence suffers.

Smart companies are learning that it pays to take a proactive, long-term approach to managing their reputation as well as investing in their brand

“Think of the HSBC tax avoidance row or the Lufthansa-Germanwings crash. BP’s Deepwater Horizon fiasco in 2010 was perhaps the first crisis played out in the full glare of social media. Arguably, it has taken BP five years to recover, at the cost of major disposals, a management decapitation and damaged share price.”

So smart companies are learning that it pays to take a proactive, long-term approach to managing their reputation as well as investing in their brand. “It is being driven by the C-suite [chiefs in the boardroom] really recognising that reputation not only has a big influence on brand in today’s society, but also it can change so quickly,” says Jeremy Thompson, chief executive of the media intelligence company Gorkana Group. Failure to prepare means a company is at greater risk when the next crisis strikes.

Matt Peacock, group corporate affairs director at Vodafone, the mobile phone giant, says: “Reputation management means doing the right thing by your customers, suppliers, shareholders, employees and communities. That’s doing, not just saying. In the digital age, no amount of dissimulation can hide the consequences of foolish or malign business decisions. The equation is simple – integrity builds loyalty which in turn creates value.”

Mr Peacock cites Blueprint for Better Business, a London-based not-for-profit organisation founded in 2011, as an inspiration because it re-establishes the idea that companies should have a “social purpose by providing goods that are good and services that serve”.

This ethos can be especially powerful internally, as a company’s own staff should be the best advocates of corporate reputation.

There are signs that Vodafone’s investment in its reputation has been working. The phone giant has come under fire in the past over allegations of tax avoidance and for handing over customer data to law enforcement agencies on the orders of national governments. Vodafone has responded by being more transparent. It voluntarily publishes a report detailing how much tax it pays on a country-by-country basis and it was the first mobile company to reveal how many demands for information it has received from law enforcement agencies.

It is not easy to measure the impact of such changes on Vodafone’s reputation, but its wider financial performance has been strong as it agreed a record-breaking £50-billion return to shareholders last year, following the sale of its share of America’s Verizon Wireless.

Mr Burt of StockWell, who has just published a book, 2020 Vision, about where business leaders see their companies at the end of the decade, says it’s important to recognise reputation is not always the catalyst for sales and profits to rise. Rather it can be a consequence of improved performance.

“In consumer businesses, three levers drive sales and profits: product quality, pricing and brand appeal,” he argues. “A rising share price and strong reputation tend to follow. In different sectors, Apple and BMW get this right. They combine smart marketing with consistent quality, justifying premium prices that underpin rising profits. Burberry and Disney also do so. It’s far harder in business-to-business sectors where success depends more on supply chain management, outstanding technology, access to resources, volume control and speed to market. In Britain, technology group ARM fits that profile.”

The proof is that Apple and ARM shares have more than doubled in three years, and Disney’s are up 150 per cent, while BMW and Burberry have roughly tripled over the period.

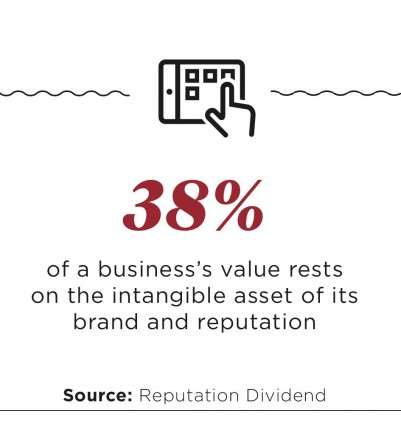

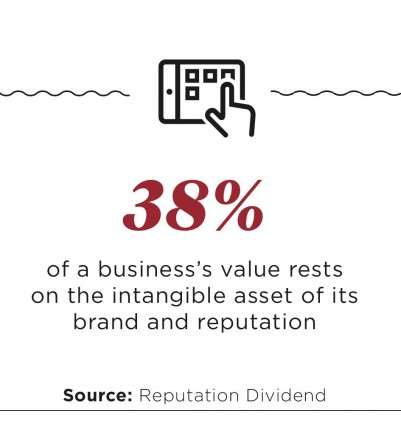

Reputation is an intangible asset that remains hard to value because it must be judged largely on qualitative measures. Devising more quantitative metrics to demonstrate its importance is a pressing issue for the PR industry, according to Gorkana’s Mr Thompson, who also chairs the trade body Amec, the international association for the measurement and evaluation of communication.

“A lot of heads of PR and comms have more access to the C-suite than they ever had before, and the chief executives and chief financial officers are pushing them to measure it [reputation],” he says. “PR is becoming a much more strategic tool – it’s having to take itself more seriously.”

Amec rejects the idea that public relations and reputation should be measured in the same way as advertising, which tends to equate the value of editorial coverage with the cost of the same amount of paid-for ad space – a concept known as advertising value equivalents.

Instead, the trade body, which drew up a manifesto called the Barcelona Principles in 2010, is keen on digital and social media data to measure “conversations” and “communities” as well as “coverage”, and to link this to the effect on business results. Even so, Mr Thompson admits it is still a battle to demonstrate an exact link between reputation and a business’s key performance indicators.

However, Mr Frohlich of Ogilvy PR believes the battle to show that reputation is as important as brand has largely been won already. “The smartest companies see that their brand and reputation are interlinked,” he says. “Their brand is their promise and their reputational health is a measure of how they are delivering on that promise. Companies who align their brand and reputation can more easily ride out short-term reputational risks, as there is always a focus and connection to the longer-term brand ambition.”

Mr Peacock at Vodafone puts it in stronger terms: “Brand, reputation and business performance are all indivisible. You are what people think you are and perception is shaped by how you behave.”

Ultimately, the value of a reputation is that it is a store of goodwill for when the next crisis strikes.

CASE STUDIES

SUCCESS

When Tim Cook came out as gay last October, the chief executive of Apple did so in his own words in an opinion piece for Bloomberg Businessweek – rather than in a TV interview – that was a master class in reputation management.

The potential risks were high both for Mr Cook and Apple. Few business leaders talk about their sexuality and, as he noted, there are plenty of states in America and other countries around the world – some of them key markets for Apple – that are homophobic.

But Mr Cook explained how he felt he owed it to gay people in less senior roles who fear coming out. “I consider being gay one of the greatest gifts God has given me,” he wrote, timing his announcement for just weeks after the record-breaking launch of the iPhone 6 and Apple’s annual results.

His decision was widely lauded – Time magazine said he had “set a new paradigm” – and it showed the former chief financial officer as a distinctive personality who had emerged from the shadow of the late Steve Jobs, Apple’s founder.

This underlined a growing view on Wall Street that Mr Cook had the confidence to pioneer new products, such as the Apple Watch, in a post-Jobs era. Apple’s share price, which had already doubled since Mr Cook took charge, has risen 20 per cent on the strength of record results since October, when he came out.

He has spoken out further, sending a tweet in March in which he condemned the US state of Indiana’s latest anti-gay legislation and linked his sexuality with the company by declaring: “Apple is open to everyone.” His comment was retweeted and favourited 30,000 times.

FAILURE

The disappearance of a passenger jet is always going to be difficult, but Malaysia Airlines’ handling of the flight MH370 disaster was widely seen as a public relations failure.

The decision to inform anguished relatives by text message, two weeks after the plane went missing in March 2014, that their loved ones were presumed dead, was the worst moment in a catalogue of mistakes.

Within hours of the plane disappearing, Malaysia Airlines struggled to communicate amid a frenzy of speculation on social networking sites.

Critics said the airline was underprepared and its top executives should have taken the lead in briefing the media, instead of initially leaving it to more junior staff. Chaotic meetings with relatives and the complex nature of the investigation, involving a state-backed airline and multiple Asian governments that were not used to public scrutiny, added to the sense of a crisis that was out of control.

Malaysia Airlines’ share price halved in three months and then their flight MH17 was shot down over war-torn Ukraine.

Hugh Dunleavy, the airline’s director of commercial, later defended the handling of MH370. “People say, ‘Why didn’t you work quicker?’” he said, but there was a deluge of “false information”. Sending a text to relatives “wasn’t done in a callous way” because the news was about to break and the airline didn’t want them to hear it first from the media.

Yet Malaysia Airlines kept making mistakes. In September, it launched a marketing campaign called My Ultimate Bucket List about things to do before you die. Two months later, it sent a tweet asking: “Want to go somewhere, but don’t know where?”

These gaffes pointed to an ongoing problem as the airline failed to manage its brand and reputation in a joined-up way.