Heading into the British summer, record highs might be fun for weather forecasts, but not for risk ratings. The bad news for supply chains is that 2016 has started historically badly.

Latest numbers from the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS) show the level of international supply chain risk rising to 79.8, which is the joint highest recorded figure for a first quarter since the CIPS Risk Index launched in 1995.

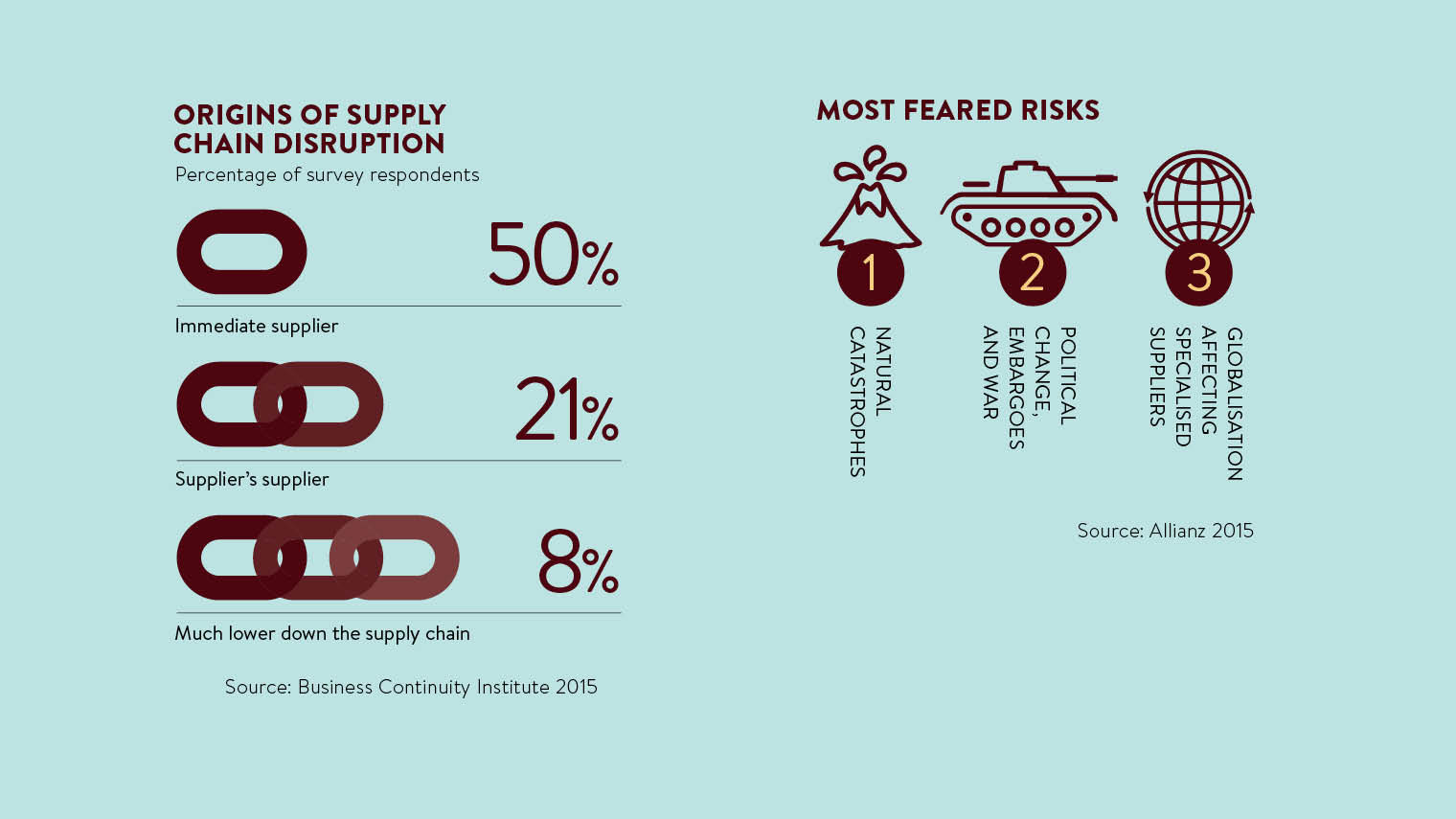

Repeated natural disasters lie behind this unwanted upward trend and supply chain management is becoming increasingly aware of climate resilience scenarios. Environmental risks range from sudden disruption via extreme weather events, to creeping effects of soil erosion. Regulatory compliance and corporate responsibility targets are also considerations.

Managing these multiple risk factors starts with collecting the necessary data, says Dexter Galvin, head of the Carbon Disclosure Project’s supply chain programme. “We’ve seen a rapid rise in buyers tackling environmental risk in supply chains. Through CDP, 89 companies with combined annual spend of over $2.7 trillion are requesting environmental data from suppliers. Many are using their spending power to drive direct action. For example, L’Oréal have demanded their top 300 suppliers have emissions reductions targets in place by 2020.”

Rising equally rapidly up the risk agenda are ethical concerns. Heightened investor, activist, media and public scrutiny is focusing hard on human rights issues, with length and complexity of supply chains no excuse.

Click here for the full infographic

The Modern Slavery Act

The food and fashion industries have already been put on notice, following high-profile supply chain management failures, including the market-cratering horsemeat scandal in Europe and the fatal Rana Plaza textile factory collapse in Bangladesh. For the UK, the prime catalyst of ethical change at present is a landmark piece of legislation – the Modern Slavery Act 2015. Its introduction in England and Wales last October means any business with turnover greater than £36 million is now required by law to make an annual declaration.

The risk is real. The 2016 Global Slavery Index from the Walk Free Foundation estimates 45.8 million people in modern slavery across 167 countries worldwide. According to the International Labour Organization, some 21 million are thought to be victims of forced labour operations.

Research conducted jointly by the Ashridge Centre for Business and Sustainability at Hult International Business School and the Ethical Trading Initiative found 71 per cent of companies admit likelihood of modern slavery in their supply chains.

For organisations tackling this supply chain pandemic, the temperature is very much set at the top, according to Quintin Lake, research fellow at Hult International Business School and co-author of the Ashridge slavery report. “Addressing modern slavery is a leadership issue,” he says. “There was clear evidence that companies with leaders, who provide strong vision and support, as well as a pathway of accountability, are able to make more progress than those who do not.”

While reputational risk is a clear corporate driver in addressing modern slavery, respondents were still keen to place humans first and centre in the human rights debate, says Mr Lake. “Risk to their reputations was agreed by 92 per cent of retailers and suppliers surveyed as the main factor driving them, though companies interviewed all felt addressing risk to workers was significant too. Most felt that mitigating risks to workers was ultimately mitigating risk to the business,” he says.

Often described as game-changing, the Modern Slavery Act has been the subject of strong media and industry attention in the UK. There still appears though to be a degree of ignorance and inactivity. The primary reason for apparent hesitation and inertia on the part of business has simply been shock, suggests Professor Jacqueline Glass, chair of architecture and sustainable construction at Loughborough University, and leader of the Action Programme on Responsible and Ethical Sourcing.

“Companies were just not ready to react and mobilise appropriately when the legislation took hold. It wasn’t in their management systems, their processes weren’t ready to be aligned and their people weren’t trained,” she says. “It’s been like a shock reverberating through company structures and people, but the pace is picking up now.”

Without proper supply chain mapping, no risk assessment can be adequately made and no resilience planning suitably thorough

A new international standard for sustainable procurement, ISO 20400, is due to be published in 2017 and there is further cause for optimism going forward, according to Shaun McCarthy, director of action sustainability and former chairman of Olympic assurance body, the Commission for a Sustainable London 2012.

“I am also very pleased to see the Institute of Human Rights and Business has taken up the challenge by promoting a permanent, global body to provide oversight to these issues. Although London 2012 did some great work in this area, they did not adequately address workers’ rights in the supply chain,” he says.

A holistic approach

For Ian Nicholson, managing director of ethical sourcing consultancy Responsible Solutions, a big bonus of the Act’s focus on data gathering has been the boost given to supply chain mapping. “Ethics are in the spotlight and a big driver for traceability, but supply chain mapping brings many other benefits. For instance, while you might think having three or four sources of a product provides some security of supply, mapping may show that all of these suppliers are actually buying from the same factory,” he says.

“The simple truth is that without proper supply chain mapping, no risk assessment can be adequately made and no resilience planning suitably thorough. If you don’t know where all your raw materials come from, how can you fully manage the risks?”

By no means all risks are external. According to Richard Wilding, professor of supply chain strategy at Cranfield School of Management, once companies start looking in the mirror, they soon realise the true value of a strategic and holistic approach.

“For a successful supply chain strategy to be developed, it has to be integrated into the competitive strategy of the business,” says Professor Wilding. “Companies need to create a supply chain risk management culture that requires everybody in the organisation, no matter what their function, to consider how any change they make is going to impact both upstream and downstream.”

Changes with consequences could be anything from switching country of supply for material sourcing, to revising payment terms for suppliers. Even incentivising sales staff differently could trigger a spike in activity with supply chain implications.

Unlike random risks, which are typically down to unpredictable external factors such as earthquakes, uncertainty generated internally within an organisation is labelled by Professor Wilding as institutionalised risk. Poor management of such risk, typified by forecasting misreads and knee-jerk overcorrection, can ultimately give rise to what is known as the bullwhip effect, where cumulative impact downstream is violent and destructive.

Soberingly, the cause of such supply chain risk is sometimes none other than the manager. Professor Wilding concludes: “Really interesting research a number of years ago looked at the behaviour of managers in the supply chain, just on inventory control. One of the findings was that 23 per cent of managers create chaos through their decision-making. What we are talking about here is deterministic chaos and this resulted in costs 500 per cent above the optimal.”

Faced with chaos, challenges and even criticism, the supply chain risk manager might be left feeling in need of a lift. The good news is that a global survey by Accenture found 76 per cent of senior executives consider supply chain risk management a priority, with more than half planning to increase investment by over 20 per cent. Almost all reported healthy returns. Summed up by the title of the Accenture megatrends report, Don’t Play it Safe When it Comes to Supply Chain Risk Management, their takeaway is this – positivity pays.