Chief executives are a busy bunch. For most, reading unsolicited “Dear CEO” letters is not top of their to-do list. But then it’s not every day one of the world’s most influential financiers picks up his pen to write.

So what was it that BlackRock’s Larry Fink felt so compelled to say? The basic message of his landmark open letter was simple: if you want your firm to prosper, it needs a “social purpose” and it needs one fast.

Finance sector waking up to the profitability of doing good

This is groundbreaking stuff, no question. Not so much the message itself. For the best part of two decades now, management gurus and business theorists have been arguing that corporations have to focus on more than just profit maximisation.

What’s remarkable about the letter is that it was written by the head of a multinational investment management corporation. This is no environmentalist fretting about saving the world’s forests. No, this is a man in charge of managing assets worth more than $6 trillion: a titan of hard-nosed finance, in other words.

The slow awakening of the financial mainstream to sustainability issues is as welcome as it is overdue. To quote the old adage, it proves that responsible business is as much about doing well as it is doing good.

Part of the argument for taking seriously non-financial issues centres around risk. Mega-trends such as climate change and population growth present huge threats to business as usual. Think of food manufacturers in a world of increasing droughts. Or transport firms in cities paralysed by gridlock.

But, as always with finance, there’s also the scent of juicy profits in the offing. Imagine the billions of dollars awaiting the company that works out how to tap methane from livestock, a major contributor to the greenhouse gas count. Or the fortunes in store for the firm that cracks global obesity?

Shifting the focus from shareholders to stakeholders

So far, so logical. But is the business world buying it? And, even if companies are genuinely trying to embrace sustainability, how are they getting on?

The verdict on both counts is mixed. On the upside, almost every chief executive these days is conversant on the importance of responsible business. Less positive is the gap between words and action, as events like the Volkswagen emissions scandal reveal only too clearly.

Stakeholder theory means putting employees, customers, communities, suppliers and the planet at the centre of business, rather than just shareholders. And this requires a total rethink, says Charmian Love, co-founder of B Lab UK, a pro-sustainability charity.

But it’s a rethink that more and more companies are seeking to make. “Around the world, we’re seeing the purpose of business being rethought so that it operates for people and planet as well as for profit,” she says.

Take Danone. With more than 100,000 employees and a market value of almost €70 billion, the French food giant is a business stalwart. Yet that didn’t stop its North American subsidiary recently qualifying as a B Corp, a certification issued by B Lab for companies practising stakeholder theory.

Other large-scale B Corps include the Brazilian cosmetics company Natura, which now owns Body Shop, and the iconic ice cream brand Ben & Jerry’s, part of Anglo-Dutch consumer conglomerate Unilever.

Moving businesses to stakeholder model not straightforward

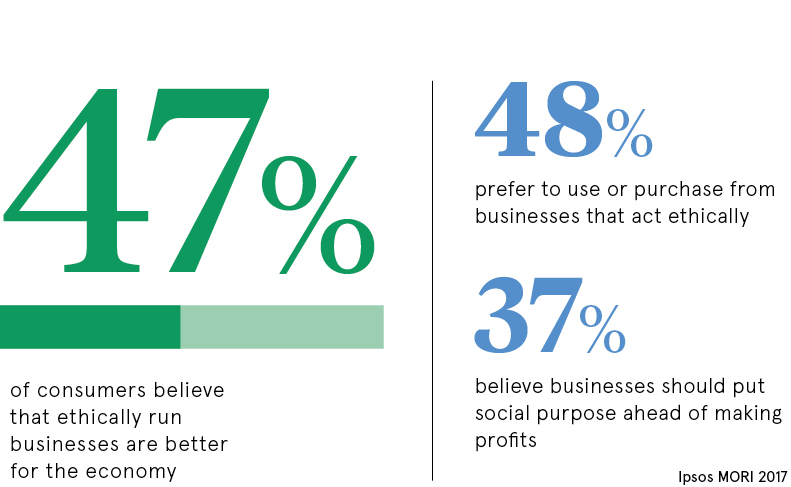

Gaining a reputation for sustainability can help firms edge ahead with consumers. Survey after survey points to the growing importance that shoppers place on social and environmental issues.

But there are other business benefits to be had as well. Lower interest rates on loans, greater operational efficiencies and a more motivated workforce are just some of the positive outcomes cited by Danone’s chief executive Emmanuel Faber.

Of course, shifting to a model based on stakeholder theory is not without its challenges. Business strategists aren’t stupid. If the economic case for operating sustainably was so clear cut, every company would already be doing it. When the payback isn’t immediate or obvious, it’s often hard for internal change agents to get a hearing.

Like ponderous oil tankers, global corporations built on shareholder primacy often find it hard to change course

That’s where leadership comes in. Without exception, the corporations leading the sustainability charge have people on their boards who, whether for reasons of head or heart, are fully behind this new way of doing business.

Stepping out so boldly takes guts, especially for a listed company with fiduciary duties to its shareholders. The sheer size of most publicly traded companies also adds additional complexities. Like ponderous oil tankers, global corporations built on shareholder primacy often find it hard to change course.

Smaller firms ahead of the curve with stakeholder theory implementation

For both reasons, the stakeholder theory trailblazers tend to be smaller firms under private ownership. As well as being more organisationally nimble, many are specifically founded to meet societal challenges. Unlike traditional companies, therefore, social purpose doesn’t have to be retrofitted, it’s there from the get-go.

The UK fairtrade chocolate brand Divine Chocolate provides just such an example. Established 20 years ago, the business was set up to better the lives of African farmers. Today, it pays a premium to its cocoa suppliers as well as reinvesting 2 per cent of its revenue in community projects.

Giving stakeholders a voice is critical to keeping Divine true to its mission, says Sophi Tranchell, the firm’s chief executive. As such, its board includes representatives from the Kuapa Kokoo co-operative in Ghana, which owns 44 per cent of the company and supplies the bulk of the cocoa for Divine’s chocolate bars.

“With representatives of Kuapa Kokoo on our board, we are supported and encouraged to do business differently with more long-term objectives,” says Ms Tranchell.

Let’s not kid ourselves, shareholders remain king. But the rise of stakeholder theory is eating into their rule. That’s good news for society at large. And, if Mr Fink is to be believed, it’s in shareholders’ economic interests too.