Nothing says mission accomplished more when it comes to the rising credibility of apprenticeships than when young people are turning down places at Oxford University in favour of on-the-job vocational learning instead.

“This is exactly what one of our new apprentices has just done,” says Sara Duxbury, head of people at law firm Fletchers, referring to one of the first learners to begin its just-launched six-year legal apprenticeship in partnership with the University of Law.

Fletchers is one of a growing number of businesses that are re-embracing a once-popular learning route that by the 1990s had almost totally fallen out of favour as university attendance sky-rocketed. By 1990 the number of apprentices in employment had fallen to just 53,000; at their peak in 1966, when 35 per cent of all men did an apprenticeship, there were 234,700, according to an Institute of Directors review of apprentices in 2003.

Apprenticeship revival

The revival of apprenticeships is undoubtedly connected to a convergence of factors all in alignment: the crippling cost students now face if they want to go university; employer dissatisfaction with the work-readiness of graduates; and the desire this creates among bosses to be more involved in developing the specific skills they know they’ll need.

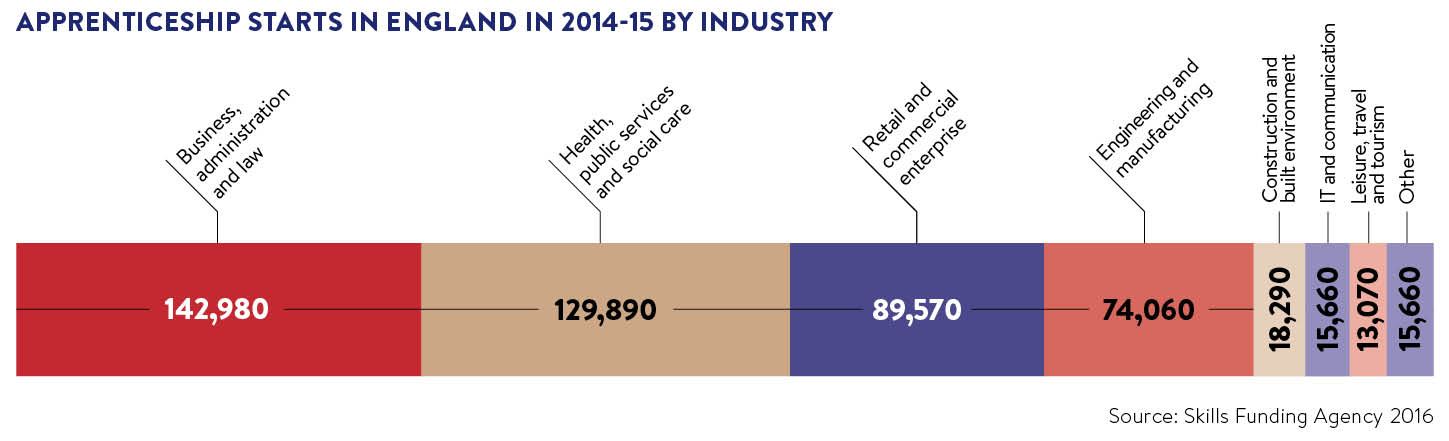

But it’s government too that has been publicising the power of apprenticeships like never before. Since the 2006 Leitch Review into the skills the UK would need by 2020, which set targets to boost apprenticeships to 500,000 a year by 2020, numerous pushes have seen Whitehall go all out to achieve its latest target of getting three million apprentices during this Parliament.

But it’s government too that has been publicising the power of apprenticeships like never before. Since the 2006 Leitch Review into the skills the UK would need by 2020, which set targets to boost apprenticeships to 500,000 a year by 2020, numerous pushes have seen Whitehall go all out to achieve its latest target of getting three million apprentices during this Parliament.

The most recent, its Get In, Go Far TV campaign, proclaims the message that apprentices are no longer just manual roles. IBM and Lloyds Bank both feature to help promote the fact that apprenticeships are now available in more than 1,500 jobs, from fashion to software development and even special effects.

“Apprenticeships absolutely had a poor reputation among employers and students alike,” says Alison Bell, human resources director at MTR Crossrail, the newly created operating company that will deliver train and passenger services on the new Elizabeth Line. “But that’s because employers had very little say in what they covered and they attracted the academically poor.

Start earning earlier

“What has changed is firms like us being able to design our own, including the industry’s first train drivers’ apprenticeship, which means that better, typically university-standard people follow. Of our 450 staff, around 109 are current or former apprentices – from level 2 (equivalent to GCSEs) through to level 5 (foundation degree level). Old apprenticeships were not fit for the future, now they are because people just want to get into work and start earning earlier.”

Such is employer participation that groups of employers, called trailblazers, are now responsible for co-developing all new apprentice standards and they often work with industry bodies to check them. For example, in July the Chartered Management Institute launched two management and leadership apprenticeships, formed in partnership with 30 employers.

In a further boost to their credibility, apprenticeships were recently given legal protection, meaning an apprenticeship can only be described as such if it creates a career path equal to higher education. But the real game-changer has arguably been the introduction of degree apprenticeships in 2015. It means young people can still achieve the equivalent of a degree, but while working and therefore without the penury that going to university would entail.

“We launched apprenticeships in 2010 and learners gain the same level-4 skills as our graduate trainees,” says IBM’s head of graduate and apprenticeship programmes Jenny Taylor, who features in the latest ads. Apprentices take three rather than two years to qualify, but she says the near-parity in speed of career development “is a huge attraction for apprentices”.

She adds: “Once qualified, we don’t pigeonhole people in terms of how they got there – they’re all on the same playing field and compete for roles thereafter on that basis. The difference though is that we pay apprentices £18,000 immediately and, once they qualify, market rates apply as they move upwards.”

[adrotate banner=“237”]

Apprentice loyality

IBM still runs a graduate scheme, but Ms Taylor already feels apprentices are more loyal, a benefit also felt by Mitchells & Butlers, operator of Harvester and All Bar One. This year it’s looking to train 1,700 apprenticeships at levels 2 to 4, compared with just 50 graduate positions, because 70 per cent of apprentices stay after one year and 90 per cent will have risen to supervisory roles in that same time.

“Our message to apprentices is very much that if they stick with us, the sky is the limit,” says Paul Capper, its vocational learning manager. “Slowly but surely, apprenticeships are no longer being seen as a second-rate option.”

Government will be glad to hear comments like this because there’s one more, but significant, change yet to come. So keen is it to engage firms still not involved with apprenticeships that from April 2017 an apprenticeship levy of 0.5 per cent will be applied to all businesses with a wage bill greater than £3 million. Levy-paying firms can get it back again if they use it to buy accredited apprenticeship training.

Some see this as more stick than carrot and groups such as the CBI have gone so far as branding it a tax. However, a sweetener is that government will give firms a £15,000 a year allowance and a 10 per cent top-up, so that for every £1 of levy paid, firms have £1.10 to spend on training.

What it will certainly do is focus firms’ minds. “Here in the NHS, the levy amount we’ll pay is equivalent to the cost of training 28,000 apprentices,” says Laura Roberts, managing director of NHS Health Education North West, who is involved with the NHS’s similarly titled Get in, Get On, Go Further apprenticeship scheme. “Currently we’re training 19,820 apprentices, so we’ll aim to see future apprenticeship numbers hit this 28,000 figure, otherwise we’ll be losing money.”

Others organisations though argue caution needs to be exercised. “We have around 1,000 apprentices at any one time, but to use all our levy, we’d need to hit 1,500,” says Sandra Kelly, head of education at Whitbread. “Chasing numbers though wouldn’t be a good thing. We need apprentices to fill a business need; real jobs do need to be there for them at the end of the day.”

HR directors worth their salt will all want to train up their own enthusiastic, high-achieving, intelligent apprentices – the change really is coming

What’s clear though is that apprenticeships, once the poor relation in education, now look unlikely to fall by the wayside as in previous years. As more school leavers want them and more good employers realise the benefit that providing them will give them, the future of learning could be apprenticeship-based.

Sharon Walpole, chief executive of Not Going To Uni, believes things have changed and this time there will be no going back. “While there’s still a problem of schools not actively promoting apprenticeships, I think we’re at the beginning of really important times,” she says. “Support for apprenticeships has historically oscillated, but I think it won’t be long before employers are no longer interested in what degree someone has done and where they got it. HR directors worth their salt will all want to train up their own enthusiastic, high-achieving, intelligent apprentices – the change really is coming.”

IMPACT OF APPRENTICESHIPS

After university tuition fee caps were nearly tripled to £9,000 in 2012, the CBI found there was an immediate 14 per cent fall in applications for arts, humanities and social sciences degrees.

However, this year record numbers of people once more applied to go to university, so experts are split about the long-term impact of the revival of apprenticeships on traditional academia.

“I still think the bulk of the action will be in the graduate market,” argues Stephen Isherwood, chief executive of the Association of Graduate Recruiters. “What I think will probably emerge is employers themselves creating more degree-apprenticeship partnerships with universities, so further education will simply develop new avenues.”

In April, £10 million of government money was pledged to help universities develop more accredited apprenticeships and firms are certainly showing an interest. This month, Be Wiser Insurance launched its own degree in insurance with the University of Chichester. Be Wiser’s Crescens George, director of learning and development, says: “The plan is to have this content converted to an apprenticeship next year.”

In April, £10 million of government money was pledged to help universities develop more accredited apprenticeships and firms are certainly showing an interest. This month, Be Wiser Insurance launched its own degree in insurance with the University of Chichester. Be Wiser’s Crescens George, director of learning and development, says: “The plan is to have this content converted to an apprenticeship next year.”

What’s certainly the case is that with degree apprenticeships giving the equivalent of a degree, apprentices are certainly challenging the concept of what it is to be a graduate. “We’re recognising this,” says Mr Isherwood. “We’re in the process of changing our name to the Institute of Student Employers.”

Apprenticeship revival