SPONSORED BY Huhtamaki

Sustainability has shot up the agenda of governments, consumers and businesses as the reality of climate change has become more visible. But, especially when it comes to the most environmentally friendly forms of packaging, there are no easy answers. Making real progress means fully understanding the built-in complexity in our global industrial processes and food systems and consumer behaviour.

The greatest challenge to reducing the environmental impact of packaging is changing consumer behaviour. Changes in all our behaviour, particularly at the end of a product’s life, are necessary to deliver a step-change in sustainability. More often, however, when simple, one-dimensional solutions aren’t available, misconceptions and biases can all too easily prevail.

Our perceptions around plastic are the perfect example. Despite the bad press it frequently gets, the reality is in some circumstances it can be the most environmentally friendly form of packaging, benefiting individuals and societies. This is not just due to its lightness, but also its ability to protect and preserve food items for longer. Without the plastic wrapped around a cucumber, for example, it would degrade much faster.

And if it wasn’t for plastic, there would be no fresh, chilled meat sold in supermarkets. Plastic helps prevent cross-contamination and works to reduce food waste substantially.

Food waste is a growing concern, with the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization estimating that if it – the food waste – was a country, it would be the third-highest emitter of greenhouse gases after the United States and China. A study last year found the carbon footprint of food waste collected from households in Scotland was nearly three times that of plastic waste.

Overall, food waste accounts for 8 per cent of the world’s total carbon emissions. This means that from a climate change point of view, reducing food waste is more important than reducing the use of plastics.

“You really have to calculate the carbon footprint for each product and look at the full life cycle, taking into account its complete supply chain,” says Richard Ali, sustainability director at Huhtamaki, a global specialist in packaging solutions for the food and drink sector.

From a climate change point of view, reducing food waste is more important than reducing the use of plastics

“Begin with what goes inside the packaging and how you ensure its properties remain intact through the supply chain so it can be safely consumed. Then consider which packaging provides sufficient protection with the least environmental burden, considering the raw material, manufacturing process and transport, as well as what happens to the packaging once the product is consumed.

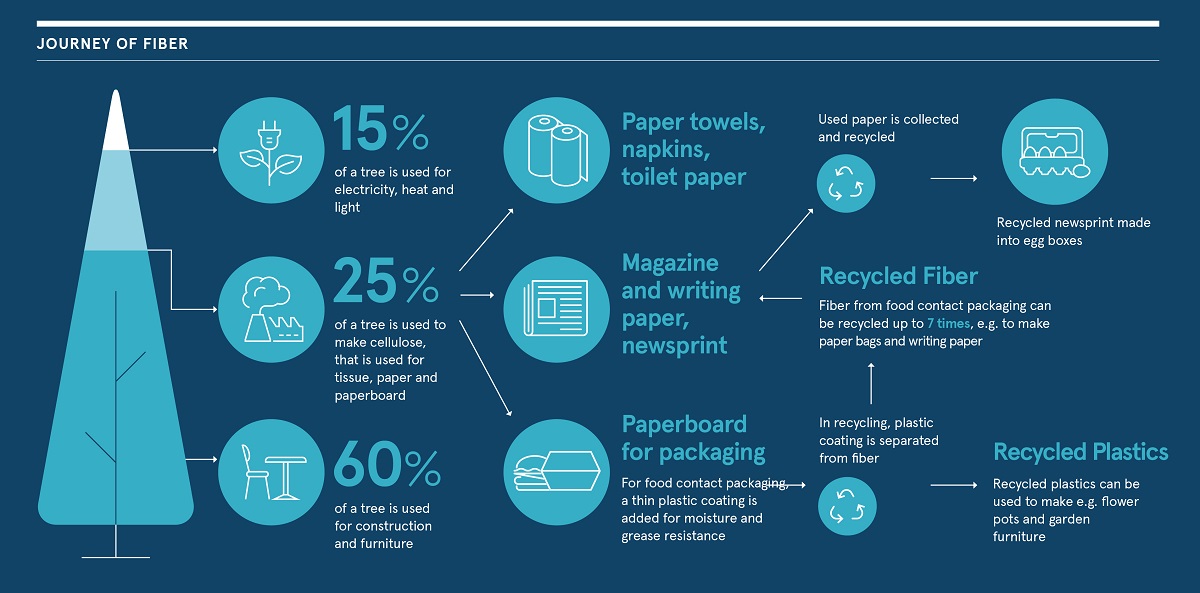

“If you deal with the packaging’s end of life properly, you can use the material again and again, and thus help save finite resources as well as cut down carbon emissions. For example, recycling can cut the carbon footprint of a paper cup by 54 per cent and the wood fibre used to make paper cups can be used up to seven times before it loses its strength.”

Public discourse around sustainable packaging is frequently shifting and, without the much-needed evidence-based discussions, consensus has still not been reached in terms of what are the most important goals that need to be achieved. In the area of environmental sustainability for packaging, is it carbon reduction, ocean plastics or biodiversity? Or should we think of the social or economic aspects of sustainability, such as jobs or food safety? There is no simple answer to solving all sustainability issues.

“People don’t buy packaging for its own sake,” says Ali. “It enables us to buy the products we want to buy, the food we want to eat. That’s why it’s so important consumers understand the role it plays in protecting the environment by reducing food waste, protecting our health by limiting cross-contamination, and making food and drink accessible and affordable to billions of people across the world. Giving food a longer shelf life allows it to move not only between geographies but through time.”

Huhtamaki seeks to design packaging that is 100 per cent recyclable, compostable or reusable. To achieve recyclability, packaging must be made as simple as possible while still delivering the safety and functionality consumers need. With a plastic pouch, for example, Huhtamaki will try to reduce the number of polymers while still achieving the shelf life people expect.

Huhtamaki mainly uses renewable raw materials, such as paper and paperboard. Even with a thin plastic coating, which is required for moisture and grease resistance or water tightness, paper-based packaging typically has a lower carbon footprint than fossil-based alternatives.

The fibre derives from sustainably managed forests where trees are planted to replace harvested timber. Wood is used in a resource-efficient way, so tree trunks are primarily used for timber and construction, treetops, branches and bark for energy production, and the rest for cellulose, from which paper and paperboard is made.

“Using the whole tree in the best way possible contributes to the economic sustainability of forests and allows more trees to be planted within a sustainably managed forest,” says Ali. “As a manufacturer, Huhtamaki takes raw materials and converts them into packaging. Doing that as efficiently and effectively as possible is not only about the design, it’s about the materials we use and our own operations.”

Huhtamaki is now committed to using 100 per cent renewable electricity and reducing its carbon impact to the extent that its operations will be carbon neutral by 2030, reducing significantly the carbon footprint of the packaging it makes. The company is also investing heavily in its efforts to work with other actors in the supply chain.

“You can design packaging to be the best it can be,” Ali adds, “but if the recycling facilities don’t exist, there will be a gap in fulfilling the circular economy. It’s about talking to other parts of the supply chain about the lower carbon footprint packaging we could create, explaining how it would need to be recycled and how that can be achieved. If we only rely on old, outdated waste-management systems, then it won’t work.

“We want a 21st-century recycling superhighway to take packaging at the end of its life and make sure the materials are recycled. This requires infrastructure that can collect, sort and recycle packaging, and put the materials back into the circular economy. Packaging delivers functionality and safety for products; the next step in the circular economy is for the material to be reused as packaging or as something different. That enables the carbon footprint of the food we eat become smaller and smaller.”

For more information please visit huhtamaki.com