Ask many Londoners what their biggest worry is and they will give you a simple answer — housing. Traffic, transport, wages and air pollution all matter, but it is housing - how much it costs, how little there is and who owns it - that really exercises the capital.

Sixteen years on since London picked its first elected mayor — and weeks until it picks its next one — the question of what future the city has under City Hall’s guidance, and whether the office has the power to effect substantive reform, looms large. Whoever wins on May 5 will need to prove it by materially impacting the tight, and tightening, housing squeeze.

As Ben Rogers, director of the think tank Centre for London says, housing is a manifestation of a London’s other — possibly larger — problems: wealth inequality and inequitable growth.

“It’s often said that London faces a housing crisis but actually it faces a growth crisis and housing is the most obvious manifestation of that. But there is huge pressure on London’s infrastructure, transport, roads, streets, pressure on work space, pressure on public services, public rail, local amenities,” he says.

Wealth gap

It is not hard to see why. At one end of the spectrum, London is home to oligarchs and royalty buying multi-million pound homes. At the other end, a one-bedroom basement flat in Finsbury Park in the north London borough of Haringey, just under six miles from central London, that once sold for £45,000 in the early 1990s is now on offer for sale at ten times that price. Worse still, the same flat has doubled in value in just six years.

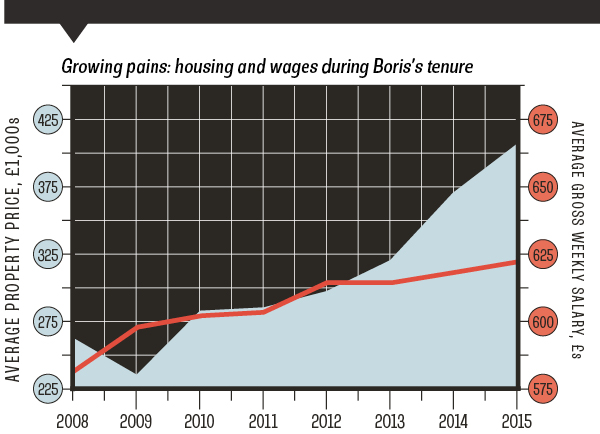

At the same time wages have stagnated during the recession that followed the 2008 financial crisis. Official figures show that between 2010 and 2014, average weekly wages in London grew by just 1.8 per cent. The average salary is £40,305, while research from KPMG last year showed an average first-time buyer would need to earn £77,000 to get onto the property ladder in the capital.

It’s an absolute crisis because for the last eight years Boris has not started the infrastructure we really need. So we have a housing crisis and public transport in chaos

According to the Centre for London, while wealth inequality is by no means a problem limited to the capital, the combination of a dominant financial services sector, rapid growth in house prices, a severe shortage of affordable housing and a squeeze on household incomes means that wealth in London “has been radically redistributed across generations and social groups”.

The Trust for London puts London’s wealth gap into sharper relief. Its research shows the top 10 per cent of employees in London receive at least £1,420 a week, £350 higher than the next highest region. But the bottom 10 per cent in London earn no more than £340, only £40 higher than the next highest region.

“It’s an absolute crisis because for the last eight years Boris has not started the infrastructure we really need. So we have a housing crisis and public transport in chaos,” London’s first elected mayor Ken Livingstone says of his successor Boris Johnson. “We are now at a point where all those people who provide the vital services we need - nurses, teachers and social workers on salaries of £25,000 - won’t be able to afford to live in London.”

Population growth

London’s population is expected to increase to around 10 million people by 2020 from 8.5 million today. Where the new arrivals will live, and how the capital’s transport system will cope with an additional 1.5 million souls is another matter. As Livingstone says: “we have got to build the houses and transport infrastructure or else it just ain’t going to work”.

It is a problem recognised by all the candidates in this year’s mayoral election. Both the Conservative candidate Zac Goldsmith and Labour’s contender Sadiq Khan have promised to build 50,000 new homes every year.

Asked whether the 50,000 homes that the two front runners have committed to building each year is enough Livingstone says: “Oh God no. We need 50,000 homes to be built each year for the next decade to come close to solving it [the housing crisis].”

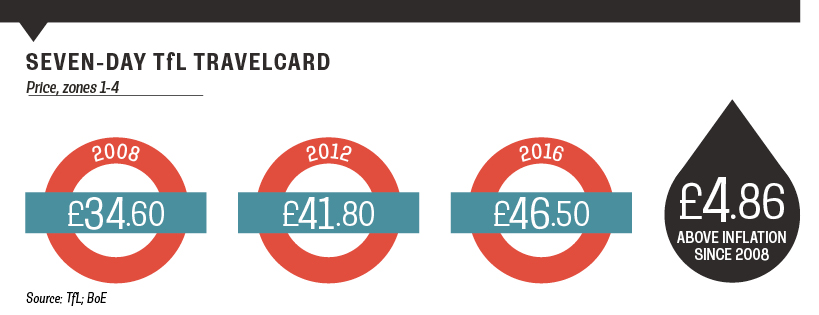

Goldsmith sees housing as being a natural consequence of continuing investment in London’s transport infrastructure – which is why he says he won’t commit to freezing tube and bus fares. Khan has talked in broad terms about council housing.

Johnson’s solution to the housing crisis has been to ride roughshod over London borough council planning committees, using one of his few direct powers as mayor of London to approve developments that have been thrown out by council planners, on no less than 14 occasions.

His latest intervention however has seen him go against the recommendations of even his own advisers regarding proposals for the Bishopsgate Goodsyard site in Shoreditch, which consists of 12 buildings of up to 46 storeys, forming what Oliver Wainwright, The Guardian’s architecture and design critic, recently called a “gargantuan cliff face on the edge of a conservation area”.

At present there are thought to be close to 300 high-rise buildings across London that have planning permission. Only a fraction will be built, but, as the Centre for London’s Rogers says, they are an inevitable consequence of London boroughs’ tighter budgets — each development will come with a small proportion of affordable housing units.

“I think the towers are a product of our finance funding policies,” he says. “The way things work now the most effective way to [fund development] is to build lots because you get affordable housing from development and you might ask developers to contribute to local infrastructure and local amenities.”

It was under Livingstone that City Hall relaxed its height restrictions; he says it was to make building affordable housing easier, not to create a free-for-all.

How London pays for what it needs is a widely acknowledged as one of the greatest challenges facing the next mayor. The solution for many however is simple: more devolution.

The Nine Elms area is undergoing major regeneration in the hope to create 20,000 new homes

Budget constraints

At present City Hall’s annual budget is around £17 billion and that covers transport, policing, fire and emergency services, and housing. But the capital generates billions more in income each year and has a population twice the size of Scotland. So why does the mayor not have tax-raising powers when the first minister of Scotland can tinker with income tax, for instance?

The London Finance Commission has argued for the devolution of all the property taxes to London — council tax, business rates and capital gains among them. Of those, so far only business rates are to be devolved to the capital, but as yet it is not clear what form that will take: whether the money will go to City Hall or directly to London boroughs. It is far from a panacea — as Rogers points out, it could create an incentive for boroughs to drive through more unpopular development to raise more money.

One thing that devolving more power to City Hall might help alleviate is the regular horse trading between the mayor and government. Rogers praises both Livingstone and Johnson for having both been big personalities who established the office of mayor as a serious force.

“They have used their soft power — the sort of megaphone that the office provides them with,” he says. “The mayor does have a lot of soft power. He is the spokesman for London, he gets listened to across the media. You have to take a meeting with the mayor if you’re the prime minister or he can make things very uncomfortable for you.”

That antipathy between City Hall and Westminster is likely to continue. Goldsmith’s opposition to a third runway at Heathrow would put him at loggerheads with central government; Khan has been the subject of vicious attacks from the Tories.

Livingstone, who knows enough about the subject having defied his party, was dropped as its candidate. He won anyway.

“When I became mayor, even though the relationship between myself and Tony Blair and Gordon Brown was poisonous, I got lots of money out of government because business said it was going to leave [the capital] because the transport network was so inefficient,” he says. “You’ve just have to look at what we were able to get out of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, even though they took steps to stop me being mayor.”

Whoever takes over in May will have to build those relationships with business, and leverage that to get what they need out of government, Livingstone says.

“They are going to have to hit the ground running,” he says. “The mayor will have to bring in good, talented people who want to get things done — not spend an eight-year administration where you spend the whole time promoting yourself and your political ambitions.”

Photos: Oli Scarf/Getty Images; Dan Kitwood/Getty Images